Try Amazon Audible Plus

‘A Conflict of Banners’

The Battle of Brunanburh 937AD.

(1). The Location, Evidence and Historical Background

by Guy Halsall

Miniature Wargames No. 27, August 1985.

Introduction

On an autumn day in 937, Athelstan ‘the Thunderbolt’ crushed an invading army at a place called Brunanburh. The location of Brunanburh has long been forgotten but Athelstan’s foes are remembered for they were the Vikings. With them were their northern allies, the Scots and Strathclyde Welsh. In one day of ‘immense slaughter’ the English routed their enemies and saved England from a repeat of the ravages of the ‘Great Army’ in the 860s and 870s.‘Never yet in this island before this by what books tell us and our ancient sages, was a greater slaughter of a host made by the edge of the sword, since the English and Saxons came hither from the east invading Britain over the broad seas and the proud assailants, warriors eager for glory, overcame the Britons and won a country.’ (1)It was a catastrophic end to an expedition which had raised such high hopes in the breasts of the Celtic and Scandinavian inhabitants of Britain who had even boasted that they would expel the English nation from the island (2). The engagement in which this incredibly optimistic invasion came to grief was remembered for two generations simply as ‘the Great Battle’. Probably the largest encounter since the departure of the Romans, Brunanburh was not to be surpassed in scale until 1066 at the earliest and it is likely that even Stamford Bridge involved less men than fought at Brunanburh. The battle remains obscure and as a result we do not know its location, the exact sizes of the forces involved or even the course of the battle. The object of this two part article will be to study the available evidence and to try to piece together a feasible account of the campaign of 937. Finally, the reconstruction of the battle as a wargame will be discussed in some detail.

The Location of Brunanburh

Like that of Degastan (MW no.3), the location of Brunanburh remains a mystery. It might seem a little self indulgent to include this discussion of the whereabouts of the battle but as its location is crucial to our reconstruction of the campaign of 937 I hope readers will forgive this little detour. Four contenders have been put forward by various authorities. These are Burnswark on the Solway firth (championed by Charles Oman), Bromborough in the Wirral, a site on one of the Humber tributaries, perhaps somewhere near Doncaster (the site supported by Michael Wood), and a spot somewhere in the Bromswold area of Huntingdonshire and Cambridgeshire (argued for by Alfred Smyth). The first of these proposed locations can, I think, now be discarded (famous last words?) as Burnswark lies in the territory of the Strathclyde Welsh whilst all our sources agree that the battle was fought on English soil. The Humber tributary location is the most popular of the proposed battle-sites and has much to be said for it. In particular, the historian ‘Florence’ of Worcester says that the Viking leader, Olaf Guthfrithson, brought his fleet into the Humber. The Bromswold was known as ‘Bruneswald’ in this period and so Brunanburh could quite logically be somewhere within its bounds. The case for this location is argued fully and convincingly by Alfred Smyth in ‘Scandinavian York and Dublin’. This leaves Bromborough. Bromborough is not an unlikely etymological progression from ‘Brunanburh’ and is the spot at which all the armies involved in the campaign could have arrived most easily.

So, which of these three sites do we choose? As will be made clear in part two of this article, there are some valid reasons for holding a Viking landing in the Humber in some scepticism. What I propose in this article is a combination of this location and the Bromborough site. Why not Smyth’s Bromswold location? In spite of his eloquent and soundly based arguments, Dr. Smyth, to my mind, never adequately explains away the presence of Scottish and Strathclyde Welsh troops this far into England. His arguments rest on an analogy with Olaf Guthfrithson’s second, successful campaign into England in 940. Now, there is surely no reason to be so certain that Olaf retraced his steps of three years previously in 940. Having received a trouncing at Brunanburh he would be more likely to change his strategy. There was a precedent for a campaign in England via the Wirrall — that of Sihtric in 920. It now remains for me to counter Smyth’s criticisms of the Bromborough location. These revolve around the statement in the ‘Song of Brunanburh’ that the West Saxons kept up the pursuit of the defeated allies ‘the whole day long’. This suggests to Dr. Smyth that the battle must have been a long way away from the sea, over which Olaf is recorded as escaping. However, if we look at this from a more military point of view than, we may suspect, Smyth did, the criticism is weakened. firstly, the ‘Song’ also states that the battle itself went on from dawn ‘til dusk. Obviously we cannot have a day-long battle and a day-long pursuit in the same twenty-four hours! So which do we accept? Since the sources agree that the battle was long and hard fought with heavy losses on both sides, it can be seen that it was the actual battle, rather than the pursuit which took up most of the day. Secondly, Bromborough is some distance from the sea. The rout could have carried the Vikings two or more miles to their ships. This is supported by my third point, which is that the terrain near Bromborough, which I have visited, is, and probably was, thickly wooded and is crossed with several streams, some of which flow through narrow but steep sided little valleys — almost ravines. Both of these features would have hampered both rout and pursuit. Fourthly, we must look at the nature of the flight from an early medieval battle. Surely calculating the distance from the battle-site to the nearest shore and dividing this by the running speed for a frightened man is not the way to calculate the length of the pursuit in terms of time taken. A defeated army would break up into clouds of fugitives which could be scattered in all directions. Obviously many, if not most, would head for the ships, if they could remember the way, but many others would simply run directly away from their pursuers. There would be skirmishes between the pursuing army and those groups of defeated troops who turned to fight when caught. The whole operation should be seen not as a race to the longships but rather as a hunt, a running fight and a headlong sprint to the boats. The pursuit, especially when it involved two tired and bloodied forces could take up a substantial amount of time without really being carried over any great distances. Therefore, whilst we must, however reluctantly, accept Professor Campbell’s gloomy conclusion that we can never know the site of Brunanburh as sadly the most likely verdict in this case, for the purposes of this article Bromborough will be assumed to be the location of the battle.

The Evidence

Athelstan’s reign is woefully under-documented. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle falls into the hands of a particularly uninspired scribe at about this time and we can only be thankful that he chose to copy out the famous ‘Song of Brunanburh’. Otherwise we may have been left ‘with the unhelpful ‘In this year King Athelstan led an army to Brunanburh’ which is all that Manuscript ‘E’ of the Chronicle has to say about the battle. Ethelweard the Chronicler devotes a mere nine lines, and Simeon of Durham in the ‘History of the Kings’ only twenty-five, to the whole reign of Athelstan. ‘Florence’ of Worcester gives us a few notices which cannot be found in the Chronicle. William of Malmesbury’s ‘De Gestis Regum Anglorum’ (‘Concerning the Acts of the Kings of the English’) is far more helpful. William copied out another poem on the battle of Brunanburh which he had found whilst compiling that part of the history. He also gives us a few independent facts about the battle. Unfortunately, this source must be treated with extreme caution for two reasons. Firstly, it was written in about 1135, almost two hundred years after the event. Secondly, William makes much use of legendary and other dubious material, though the poem seems to be genuine, and it is often difficult to decide what is spurious and what is genuine in his work. Other English sources consulted in the preparation of this article were the ‘History of the English’ of Geoffrey Gaimar, the History of Ingulf of Crowland, Simeon of Durham’s ‘History of the Church of Durham’ and the Chronicle of Melrose. On the Scandinavian side, apart from a couple of passing references in the Heimskringla, we have only the saga of Egil Skallagrimsson, an Icelandic epic written about an adventurer who fought in Athelstan’s army at Brunanburh, which battle it calls ‘Vin Moor’ or ‘Vin Forest’. This is the only source which claims to give an account of the course of the battle. It now seems likely that, as Smyth has argued, we can overrule Campbell’s claim that this chapter of the saga is a confusion with an earlier battle on the Don (!). Unfortunately this source is still even more dubious than William of Malmesbury’s work. The saga is wildly incorrect about the allied commanders, although it is possible to see why its compiler went wrong, and, moreover was not written down until c. 1230 almost three hundred years after the battle. Like most sagas it tends to over-emphasise the role of the hero. From Ireland we have the Annals of Ulster, which provide what is perhaps the earliest reference to the battle, the Annals of Inisfallen which, whilst they make no mention of the battle furnish one piece of, perhaps, important information in relation to the circumstances of the campaign, and finally the Annals of Clonmacnoise which give a most interesting list of the allied leaders in the battle. The Welsh annals give only a bald notice of the ‘battle of Brune’. In addition, Smyth refers to a source which I have been unable to study first hand, Johannes Fordun’s ‘Chronica Gentis Scotorum’ which also furnishes some valuable information. These then are our sources. It remains for us to see what sort of coherent story can be made from them.

The Historical Background

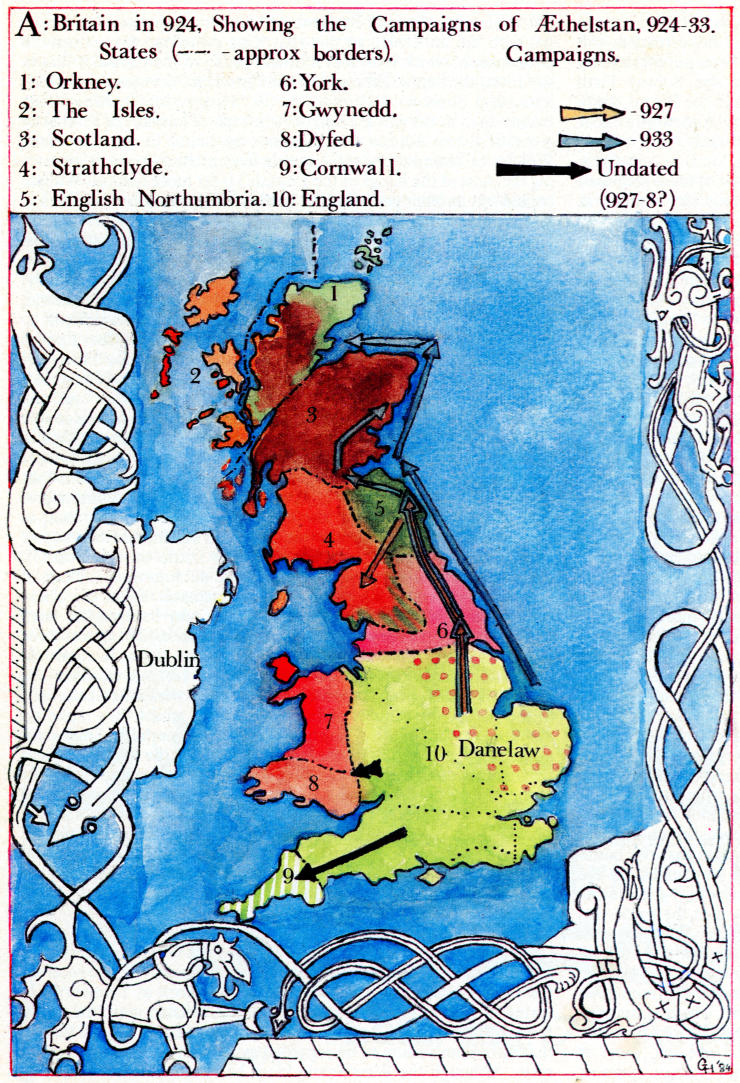

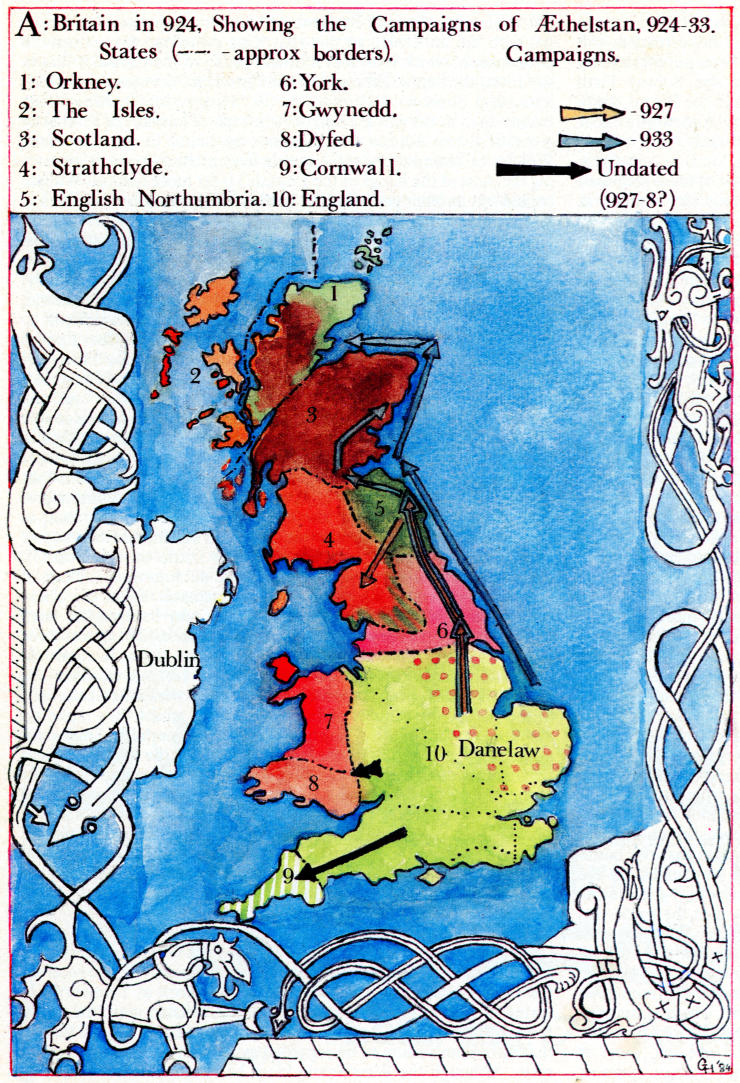

Athelstan, the eldest grandson of Alfred the Great, succeeded his father, Edward I ‘the Elder’, in 924. On 30th January 925 he received the submission of King Sihtric ‘One-eye’ of York at Tamworth. In spring of 927, however, Sihtric died and Athelstan marched north, forcing Sihtric’s sons, Anlaf and Guthfrith, to flee. It is upon this act that Atl1elstan’s claim to be regarded as the first King of all England rests. Although the West Saxon kings had enjoyed suzerainty over Northumbria since the days of Ecgbert (see the article on Ecgbert’s victory at Ellendun) the claim was a somewhat nebulous one which had become something of a farce in the darkest days of the Danish invasion. Athelstan was the first king to rule Northumbria directly (3). Soon after this success, he brought English Northumbria under his control. On 12th July 927 he received the submission of all the kings of Britain from Wales to the Great Glen (4) and was indeed ‘Emperor of Britain’.

Marching south, Athelstan met the Welsh princes again, this time at Hereford and forced them to pay him an annual tribute, allegedly of 20 pounds of gold, 300 of silver and 25,000 oxen in addition to as many hunting dogs and birds as he chose. It was a humiliation which the Welsh would remember bitterly.‘The stewards of Caer Geri will lament it bitterly, in valley and on hill, some do not deny it — not fortunately did they come to Aber Peryddon, Afflictions are the taxes they will collect.’ (Armes Prydein)From Hereford, Athelstan marched south again and scents to have stamped out the last embers of Cornish independence in a lightning campaign (5). Six years of peace followed but in 933 he was at war again. This time the enemy was Constantine II, the king of Scotland whose submission Athelstan had received in 927. The reason for the war was that Constantine had broken his word and, according to modern writers, was harbouring Anlaf Sihtricsson, the exiled son of Sihtric ‘One-Eye’. This latter assertion is based on unclear evidence, and seems improbable, though not impossible. Certainly, Anlaf can hardly have been ‘leader of an Irish pirate fleet’ or had ‘designs on ... Northumbria’ — he cannot have been more than about thirteen at the time! Anyway, Athelstan gathered his Welsh vassals and marched north with a fleet in support. Constantine was unable to resist and, after the English had ravaged his kingdom, he submitted, giving his son as a hostage. The giving of hostages from one ruler to another was a traditional Celtic sign of clientship. Constantine would not forget this insult.

For the next three years Constantine was involved in making an alliance against Athelstan. In this diplomatic activity he was supremely successful. helped, no doubt, by another of Athelstan’s ‘Imperial assemblies’, this time at Cirencester in 935. Here he again received the submission of three Welsh Princes, Constantine of Scotland and Eugenius of Strathclyde.

Smyth has rightly pointed out that we should not view the background to Brunanburh purely in these terms. We must cross the Irish Sea to Dublin and examine the role of Olaf Guthfrithson. Olaf was the son of a grandson of the famous Ivarr ‘the Boneless’ and thus heir to the claim of his family to the kingdom of York. When his uncle, Sihtric, died the claim devolved upon his father, Guthfrith, but Guthfrith, insecure in Ireland had been unable to press the claim and oppose that of the House of Wessex and had died in 934. Thus Olaf, as the eldest eligible male of this house. inherited the claim to York. In the next three years he built up his power in Ireland and took steps to secure the friendship of Athelstan’s enemies in Britain. He seems to have been given the hand of Constantine’s daughter in marriage, though there is, as ever, some confusion about the Viking leaders and it could have been Anlaf Sihtricsson who became the King of Scots’ son-in-law (6). In August 937 Olaf defeated the men of Limerick, his most dangerous Norse rivals, and marched them back to Dublin, where he presumably pressed them into his service. His Irish base secured, Olaf was ready to join Constantine and his allies. The confederacy against England was composed of Scotland, the Irish Vikings, Strathclyde, (‘?) the Gall-Gaedhel (Hiberno-Norse marauders), (?) the Kingdom of the Isles, (?) the Vikings of Caithness and Orkney and (?) the North Welsh (7). Some Irishmen may also have joined Olaf’s army. The decisive campaign was about to commence.

Notes

1. The Song of Brunanburh in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle s.a 937.

2. This is the impression given by the contemporary poem ‘Armes Prydein’.

3. Scandinavian sources record that, at the end of his reign, Athelstan allowed a certain Eric ‘Blood-Axe’ (who?) to rule Northumbria as a sub-king.

4. The Great Glen marked the approximate border between Scotland and the Norse settlements of Caithness, &c.

5. Though some modem writers, notably Oman, have claimed that William of Malmesbury’s statements about this are false, in the final analysis they seem to be authentic. They do tally with a later letter concerning the church in Cornwall (E.H.D. Vol I, document 229, pp.892-4.) which confirms that Athelstan did have dealings with this part of the world at this time.

6. The two rulers are often confused as they have the same name. I have here given the son of Sihtric ‘One-Eye’ the Irish version of Olaf, Anlaf, for the sake of clarity.

7. The allies marked with question marks may or may not have been involved in the 937 campaign. Two or three Gall-Gaedhel names are recorded in the Annals of Clonmacnoise as amongst the fallen, as is the King of the Isles. The Caithness settlements subject to Orkney had been raided by Athelstan’s fleet in 933 and so would have had good reason for supporting Constantine. The North Welsh may have taken part as Gaimer records Welsh, as well as ‘men of Cumberland’ (i.e. Strathclyde Welsh) at Brunanburh. One of the leaders of the allies at Brunanburh, according to Egil’s saga was an ‘Earl Adils’. This could be a corruption of Idwal, the name of the ruler of Gwynedd.

In part two...The Campaign, The Battle & The Wargame....