Try Amazon Fresh

|

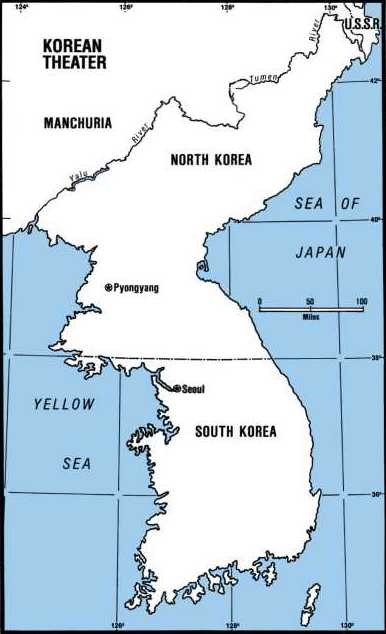

Designated Campaigns of Korean ServiceThe U.S. Army designated 10 campaigns, adopted by the U.S. Air Force, for Korean Service. The first campaign began on June 27, 1950, when elements of the U.S. Air Force first countered North Korea's invasion of South Korea, and the last one ended on July 27, 1953, when the Korean Armistice cease-fire became effective. In all designated campaigns, the combat zone for campaign credit is the Korean Theater of Operations, which encompassed North and South Korea, Korean waters, and the airspace over these areas. The Secretary of Defense extended the period of Korean Service by 1 year from the date of the cease-fire. During this time, units and individuals earned no campaign credits, but received the Korean Service Streamer or the Korean Service Medal and Ribbon if stationed in Korea. The first campaign for Korean service is the UN Defensive. |

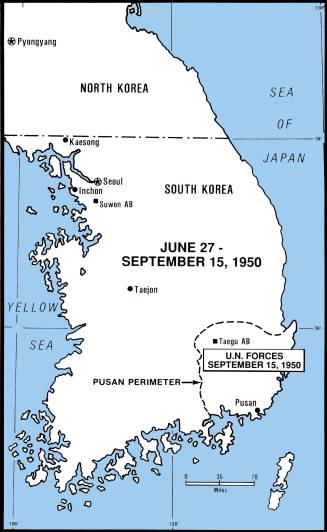

Early on June 25, 1950, North Korean forces crossed the 38th parallel near Kaesong to invade the Republic of Korea (ROK).* During the afternoon, North Korean fighter aircraft attacked South Korean and U.S. Air Force (USAF) aircraft and facilities at Seoul airfield and Kimpo Air Base, just south of Seoul. The next day, Far East Air Forces (FEAF) fighters flew protective cover while ships evacuated American citizens from Inchon, a seaport on the Yellow Sea, 20 miles west of Seoul. With the Communists at the gates of Seoul, on June 27 FEAF transport aircraft evacuated Americans from the area. Fifth Air Force fighters escorting the transports destroyed 3 North Korean fighters to score the first aerial victories of the war. Meanwhile, in New York the United Nations (UN) Security Council, with the Soviet Union's delegate absent and unable to veto the resolution, recommended that UN members assist the Republic of Korea. President Harry S. Truman then ordered the use of U.S. air and naval forces to help counter the invasion. The Far East Air Forces, commanded by Lt. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, responded immediately. On June 28 FEAF began flying interdiction missions between Seoul and the 38th parallel, photo-reconnaissance and weather missions over South Korea, airlift missions from Japan to Korea, and close air support missions for the ROK troops. North Korean fighters attacked FEAF aircraft that were using Suwon airfield, 15 miles south of Seoul, as a transport terminal and an emergency airstrip. The next day the 3d Bombardment Group made the first American air raid on North Korea, bombing the airfield at Pyongyang. The FEAF Bomber Command followed this raid with sporadic B-29 missions against North Korean targets through July. Then in August the B-29s made concerted and continuous attacks on North Korean marshaling yards, railroad bridges, and supply dumps. These raids made it difficult for the enemy to resupply, reinforce, and move its front-line troops. As Communist troops pushed southward, on June 30, 1950, President Truman committed U.S. ground forces to the battle. Shortly afterward, on July 7, the UN established an allied command under President Truman, who promptly named U.S. Army Gen. Douglas MacArthur as UN Commander. A few weeks later, on July 24. General MacArthur established the United Nations Command. Meantime, the Fifth Air Force, commanded by USAF Maj. Gen. Earl E. Partridge, established an advanced headquarters in Taegu, South Korea, 140 miles southeast of Seoul. Headquarters, Eighth U.S. Army in Korea, under U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker, was also set up at Taegu. During July 1950, as UN forces continued to fall back, most FEAF bombers and fighters operated from bases in Japan, over 150 miles from the battle front. This distance severely handicapped F-80 jet aircraft because of their very short range, even when equipped with wing fuel tanks. After only a short time over Korean targets, the F-80s had to return to Japan to refuel and replenish munitions. Cooperating with naval aviators, the USAF pilots bombed and strafed enemy airfields, destroying much of the small North Korean Air Force on the ground. During June and July, Fifth Air Force fighter pilots shot down 20 North Korean aircraft. Before the end of July, the U.S. Air Force and the Navy and Marine air forces could claim air superiority over North and South Korea. UN ground forces, driven far to the south, had checked the advance of North Korean armies by August 5. A combination of factors--air support from the Far East Air Forces, strong defenses by UN ground forces, and lengthening North Korean supply lines--brought the Communist offensive to a halt. The UN troops held a defensive perimeter in the southeastern corner of the peninsula, in a 40- to 60-mile arc about the seaport of Pusan. American, South Korean, and British troops, under extensive and effective close air support, held the perimeter against repeated attacks as the United Nations Command built its combat forces and made plans to counterattack. *The Republic of Korea was established by the United Nations on August 15, 1948, with Seoul as the capital city. North Korea, the Democratic Republic of Korea, was established on September 9, 1948, under a Communist regime with its capital at Pyongyang. In June 1950, the boundary between North and South Korea was the 38th degree, North latitude; i.e., the 38th parallel. |

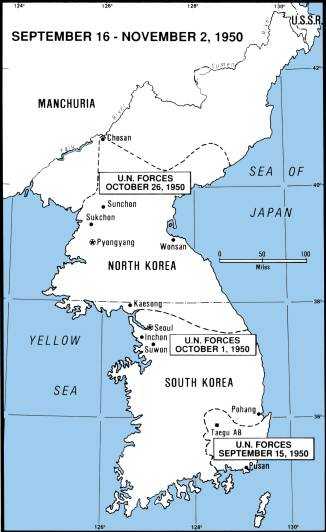

The first UN offensive against North Korean forces began on September 15, 1950, with the U.S. X Corps, under Army Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond, making an amphibious assault at Inchon, 150 miles north of the battle front. In the south, the Eighth U.S. Army, made up of U.S., ROK, and British forces, counterattacked the next day. The 1st Marine Air Wing provided air support for the landing at lnchon while the Fifth Air Force likewise supported the Eighth Army. On September 16, as part of a strategic bombing campaign, the FEAF bombed Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, and Wonsan, an east coast port 80 miles north of the 38th parallel. U.S. Marines attached to X Corps captured Kimpo Air Base near Seoul on September 17. Two days later the first FEAF cargo carrier landed there, inaugurating an around-the-clock airlift of supplies, fuel, and troops. C-54, returned wounded personnel to hospitals in Japan, and C-119s airdropped supplies to front-line forces. Bad weather hindered close air support of the Eighth Army, but on the 26th the L1.S. 1st Cavalry Division forged out of the Pusan Perimeter north of Taegu and within a day thrust northward to link up with 7th Infantry Division forces near Osan. 25 miles south of Seoul. Air controllers, using tactics similar to those developed in France during World War II, accompanied the advancing tank columns, supported tank commanders with aerial reconnaissance, and called in close air support missions as needed. On September 26, General MacArthur announced the recapture of Seoul, but street fighting continued for several more days. For a time in August and September 1950. before the recapture of Kimpo, all FEAF flying units had to fly from bases in Japan. The only continuously usable tactical base in Korea was Taegu, which the FEAF used as a staging field to refuel and arm tactical aircraft. On September 28 fighter-bombers returned permanently to Taegu. As US forces swept North Korean troops from South Korea, aviation engineers rebuilt the airfields, beginning with Pohang, on the east coast 50 miles northeast of Taegu. USAF flying units returned on October 7 to Pohang and to other rebuilt airfields at Kimpo, near Seoul, and at Suwon, 20 miles south of Seoul. Supported by a UN resolution, President Truman directed the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff to authorize pursuit of the retreating North Korean forces, and on October 9 the Eighth Army crossed the 38th parallel near Kaesong. American and South Korean forces entered the North Korean capital of Pyongyang on October 19. FEAF B-29s and B-26s continued to bomb surface transport lines and military targets in North Korea, while B-26s, F-51s, and F-80s provided close air support to ground troops. FEAF also furnished photographic reconnaissance, airlift, and air medical evacuation. For example, on October 20 the air force's troop carriers delivered 2,860 paratroopers and more than 301 tons of equipment and supplies to drop zones near Sukchon and Sunchon, 30 miles northeast of Pyongyang. The air-borne troops by-passed strong defenses established by the North Koreans, and taken by surprise, the enemy troops abandoned their positions to retreat further northward. Meantime, on the east coast of Korea, the ROK forces crossed the 38th parallel on October I and 10 days later captured Wonsan. On October 26 South Korean forces reached the Yalu River at Chosan. 120 miles north of Pyongyang. Communist forces counterattacked within 2 days along the ROK lines near Chosan, forcing the South Koreans to retreat. The People's Republic of China had entered the conflict against the Eighth U.S. Army in Korea in the west, and the U.S. X Corps in the east. At this point, the war in Korea took on an entirely different character as the tide turned against the UN forces. |

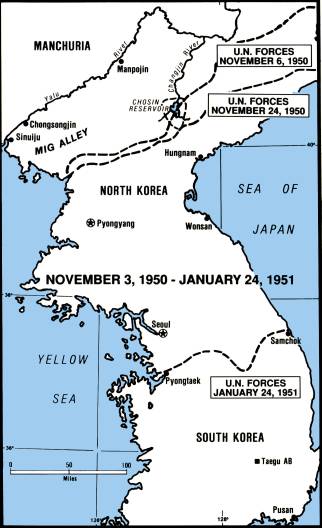

With Chinese troops fighting in North Korea against UN forces, on November 3, 1950, UN troops, under the protection of Fifth Air Force close air support, began to withdraw to the Chongchon River in northwest Korea. On November 8 FEAF bombed the city of Sinuiju. the gateway from Korea to Manchuria on the Yalu River. Chinese MiG-15 jet aircraft engaged the F-80 jets flying cover for the U.S. bombers, and in the first all-jet aerial combat, an American pilot scored a victory against a MiG. During the rest of November, FEAF medium and light bombers, along with U.S. Navy aircraft, attacked bridges over the Yalu River and supply centers along the Korean side of the river. The operations against bridges were usually unsuccessful because the bombers had to fly parallel to the river to avoid violating Chinese air space. B-29s also dropped their bombs from at least 20,000 feet to avoid flak. Nevertheless on November 25 the bombers destroyed a span of a railroad bridge at Manpojin, 150 miles north of Pyongyang, and on November 26 two spans of a highway bridge at Chongsongjin. 110 miles northwest of Pyongyang. The Communists simply built pontoon bridges or, as winter set in, crossed the Yalu on the ice. The B-29s did destroy North Korean supply centers, thus forcing the enemy to disperse its supplies or to hold them in Manchuria until needed. The United Nations Command planned a new offensive, unaware of the extent of the Chinese involvement. Even as General MacArthur kicked off the offensive on November 25-26, 1950, the Communist forces also launched a major attack, driving both the Eighth Army in northwest Korea and the X Corps in northeast Korea southward. In the Chosin Reservoir area, the U.S. 1st Marine Division was surrounded. Between December 1 and 11, the FEAF Combat Cargo Command, commanded by Maj. Gen. William H. Tunner, airlifted over 1,500 tons of supplies to the embattled Marines. FEAF pilots even dropped 8 bridge spans so that the Marines could build a bridge across a gorge. The division finally broke through the Chinese troops to UN lines near Hungnam, an east coast seaport 100 miles northeast of Pyongyang. The U.S. Navy, with some assistance from FEAF airlifters, evacuated the X Corps from Wonsan on December 5-15 and from Hungnam on December 15-24, leaving northeast Korea to the Communist forces. On the 27th the X Corps passed to the control of the Eighth Army, and by the end of the month, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, UN Commander, had placed Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, who had just arrived in Korea to replace General Walker, in control of all UN ground forces in Korea. Meanwhile, the FEAF had brought additional C-54s to Korea to meet the demands of the ground forces for theater airlift, and the air force began moving its tighter units, including a squadron of South African Air Force fighters, to airfields in North Korea, in order to meet the close air support needs of UN troops. The appearance of the MiG-15 jet fighter in November 1950 threatened UN air superiority over Korea because the MiG outperformed available U.S. aircraft. The FEAF requested the newest and best jet fighters, and on December 6, less than a month later, the 27th Fighter-Escort Wing, flying F-84 Thunderjets, arrived at Taegu. Then on December 15 the 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wing flew its first mission in Korea in F86 Sabrejets. Less than a week later, on the 22nd, the F-86 pilots shot down 6 MiG-15s, losing only 1 Sabrejet. The newer jet fighters permitted the UN Command to maintain air superiority. During December 1950 the FEAF flew interdiction and armed reconnaissance missions that helped slow the advancing Chinese armies. B-29s and B-26s bombed bridges, tunnels, marshaling yards, and supply centers. When the Chinese troops resorted to daytime travel north of Pyongyang in pursuit of the Eighth Army, Fifth Air Force pilots killed or wounded an estimated 33,000 enemy troops within 2 weeks. By mid-December Communist forces were moving only at night, though still advancing. On January 1, 1951, Communist forces crossed the 38th parallel and 3 days later entered Seoul behind retreating UN troops. Finally, on January 15 UN forces halted the Chinese and North Korean armies 50 miles south of the 38th parallel, on a line from Pyongtaek on the west coast to Samchok on the east coast. |

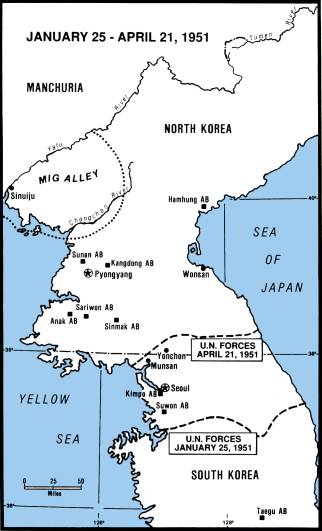

Taking the offensive on January 25, 1951, the UN Command began military operations directed toward wearing down the enemy rather than capturing territory. For 2 weeks UN forces, with close air support provided by Fifth Air Force fighter-bombers, advanced slowly northward against inconsistent but often stubborn resistance. On February 10 the troops captured Kimpo Air Base near Seoul. When thawing roads made ground transport virtually impossible, Brig. Gen. John P. Henebry's 315th Air Division airdropped supplies to the ground forces. For example, between February 23 and 28 the 314th Troop Carrier Group, flying C-l 19s, dropped 1,358 tons of supplies to troops north of Wonju, a town 50 miles southeast of Seoul. UN forces reoccupied Seoul on March 14. A few days later, on March 23, the Far East Air Forces airdropped a reinforced regiment at Munsan, 25 miles north of Seoul. In preparation, fighter-bombers and medium bombers, under direction of airborne tactical controllers, bombed enemy, troops and positions near the drop zones. The C-l19s continued the airdrop of supplies until March 27, as the paratroopers advanced from Munsan to Yonchon, 35 miles north of Seoul. By this time, Communist forces had established such a strong air presence between the Chongchon and Yalu Rivers in northwestern Korea that Fifth Air Force pilots began to refer to this region as "MiG Alley." The Fifth, unable to challenge the enemy's temporary air superiority in northwestern Korea from bases in Japan, returned its tactical fighter units to Korean airfields recently wrested from Communist control. By March 10, F-86 Sabrejets were once again battling Chinese and North Korean pilots in MiG Alley while flying cover for FEAF Bomber Command's B-29s against targets in the area. Through the rest of March and April, FEAF bombed bridges over the Yalu River and other targets under the protection of escorting jet fighters. In spite of the escorts, MiG pilots on April 12 destroyed 3 of 38 B-29s attacking bridges at Sinuiju, causing the FEAF Bomber Command to put Sinuiju temporarily off-limits to B-29s. On tbe eastern side of the peninsula, the Bomber Command carried on an interdiction campaign against railroads, tunnels, and bridges. U.S. naval aviators also were conducting missions against targets in the northeastern section of Korea between Wonsan and the Siberian border. From April 12 to 23 the FEAF Bomber Command attacked rebuilt airfields on the outskirts of Pyongyang, at Sariwon, 40 miles south of Pyongyang, and at Hamhung, on the east coast 110 miles northeast of Pyongyang. On the ground, the Eighth Army pushed north of Seoul to reach the 38th parallel on March 31. Soon after, on April 11, President Harry S. Truman removed the UN Commander, General Douglas MacArthur, because of his outspoken criticism of the President's prosecution of the war. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway replaced General MacArthur, and Lt. Gen. James A. Van Fleet inherited the Eighth Army command. With close air support from the Fifth Air Force, UN ground forces pushed north beyond the 38th parallel between April 17 and 21, until halted by a North Korean and Chinese counterattack. |

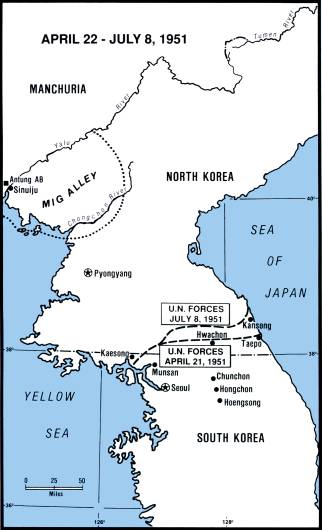

The Chinese Communist Forces' spring offensive began on April 22, 1951, with an assault on Republic of Korea Army positions 40 to 55 miles northeast of Seoul. United States Army and Marine forces joined a United Kingdom brigade to plug the gap opened in UN lines north of Seoul, and by May 1 the Communist drive had lost momentum. For the next 2 weeks the Chinese and North Koreans built their strength before attacking in the vicinity of Taepo, between the east coast and Chunchon, 45 miles northeast of Seoul. By May 20 Eighth Army forces had stopped the Communist troops just north of Hongchon, 50 miles east of Seoul. The UN Command launched a counterattack 2 days later, on the 22nd. along most of the battle line, except for a holding action just north of Munsan. ROK forces on the east coast quickly advanced northward to Kansong, 25 miles north of the 38th parallel. Advance in the center of the peninsula was slower, but by May 3 1 the Communist forces had their backs to Hwachon, 65 miles northeast of Seoul. Further west, UN troops had pushed the enemy troops to Yonchon, 40 miles north of Seoul. During the CCF Spring Offensive, the Far East Air Forces and the U.S. Navy maintained air superiority over Korea through aerial combat and continued bombing of North Korean airfields. The Fifth Air Force and a U.S. Marine air wing extended airfield attacks on May 9 to include Sinuiju airfield in the northwest corner of Korea. MiG fighters from Antung airfield just across the Yalu River in Manchuria offered little resistance to the American raid. Jet fighter-bombers destroyed antiaircraft positions, followed by Marine Corsairs and Air Force Mustangs that bombed and rocketed targets around Sinuiju airfield. F-86s protected the attack aircraft from MiGs. This mission destroyed all North Korean aircraft on the field, most buildings, and several fuel, supply, and ammunition dumps. All U.S. aircraft returned safely from the Sinuiju raid. General Stratemeyer, Commander of FBAF, suffered a heart attack in May 1951, and General Partridge became Acting Commander while Gen. Edward I. Timberlake temporarily took over the Fifth Air Force. Maj. Gen. Frank F. Everest succeeded to the command of the Fifth Air Force on June 1, and 10 days later, Lt. Gen. O. P. Weyland took over FEAF. Through most of May the Chinese pilots stayed on the Manchurian side of the Yalu River, but on the 20th 50 MiGs engaged 36 Sabres in aerial combat. During this fight Capt. James Jabara destroyed 2 MiGs. Added to his 4 previous victories, these credits made him the first jet ace in aviation history. MiG pilots again challenged Sabre flights escorting B-29 bombers on May 31 and June 1, but the Communists lost 6 more aircraft. FEAF, Marine, and Navy close air support of the UN ground forces, coupled with extensive artillery fire, forced the North Korean and Chinese forces during the spring of 1951 to restrict their movements and attacks to periods of darkness and bad weather. In addition, the air force used ground-based radar with considerable success to direct B-29 and B-26 night attacks against Communist positions and troop concentrations. The FEAF also supplemented sealift with its cargo aircraft by flying supplies, mostly artillery ammunition and petroleum products, from Japan to Korea. Transports usually landed at Seoul or Hoengsong, 55 miles southeast of Seoul; the 315th Air Division delivered 15,900 tons in April, 21,300 tons in May, and 22,472 tons in June 1951. Also, whenever rains slowed overland transport to the front lines, C-119s airdropped supplies to UN troops. In late May FEAF initiated Operation Strangle, an interdiction campaign aimed at highways south of the 39th parallel. The next month the campaign was extended, with somewhat greater success, to railroads. On June 23, 1951, the North Koreans, through the Soviet Union, proposed a cease-fire, and in July delegations began negotiations at Kaesong, North Korea, on the 38th parallel 35 miles northwest of Seoul. UN forces continued pushing the Communist troops northward until by July 8 the front line correlated closely with the armistice line established 2 years later. |

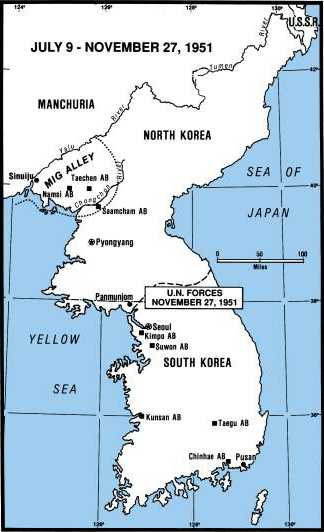

Although truce negotiations began on July 10, 1951, hostilities continued. When the parties suspended negotiations on August 23, the UN Command conducted an offensive in central Korea, to gain an important tactical position. But overall the UN ground forces fought a war of attrition. When the ground action subsided, the Far East Air Forces began to improve its Korean airfields. The Allies distributed their air power on the improved airfields throughout South Korea. In July 1951 the Royal Australian Air Force sent a squadron of jet fighters to Kimpo airfield, on the western outskirts of Seoul. U.S. Air Force units assigned to Kimpo included a fighter-interceptor group and a tactical reconnaissance group. A South African Air Force fighter-bomber squadron, flying Mustangs, operated from Chinhae airfield on the south coast, 10 miles west of Pusan. The USAF also stationed a fighter-bomber group at Chinhae. Other major UN airfields in Korea included 2 at Pusan, 1 with a Marine air wing assigned and the other hosting a USAF light bomber group. The USAF had stationed 2 fighter-bomber groups at Taegu, 140 miles southeast of Seoul; a fighter-bomber group and a fighter-interceptor group at Suwon, 15 miles south of Seoul; and a light bomber group at Kunsan, on the west coast 110 miles south of Seoul. The FEAF and Fifth Air Force used other airfields in South Korea primarily as staging bases from which to rearm and refuel aircraft, make emergency landings, and fly in supplies for front-line troops. The B-29s and cargo carriers operated from bases in Japan. The Chinese Air Force implemented an air campaign in late July to test UN air superiority. Through August the Communist pilots tried their tactics in scattered air battles, then in September they challenged Fifth Air Force pilots in earnest. During the month UN pilots engaged 911 Communist aircraft in aerial combat and shot down 14 MiGs, while suffering 6 losses. Aggressive Communist pilots nonetheless forced the Fifth Air Force to suspend tighter-bomber interdiction attacks in MiG Alley until the winter, and on October 28 FEAF Bomber Command restricted the vulnerable B-29s to night operations. The Chinese Air Force implemented an air campaign in late July to test UN air superiority. Through August the Communist pilots tried their tactics in scattered air battles, then in September they challenged Fifth Air Force pilots in earnest. During the month UN pilots engaged 911 Communist aircraft in aerial combat and shot down 14 MiGs, while suffering 6 losses. Aggressive Communist pilots nonetheless forced the Fifth Air Force to suspend tighter-bomber interdiction attacks in MiG Alley until the winter, and on October 28 FEAF Bomber Command restricted the vulnerable B-29s to night operations. UN fighter-bombers, no longer able to attack targets in MiG Alley, turned to the destruction of railway lines in the area between Pyongyang and the Chongchon River. On August 18 the UN Command expanded its railway interdiction campaign. The Fifth Air Force attacked railroads and bridges in the northwest but outside MiG Alley; FEAF Bomber Command hit transportation targets, especially bridges, in the center of North Korea; and U.S. Navy aerial units bombed railroads and bridges on the northeast coast. This campaign forced the Communists to resort to motor vehicles and to move supplies and troops at night. Thus, in August and September night-flying B-26s found lucrative targets on the roads of North Korea. Stronger flak defenses and worsening weather in October and November permitted the Communists to repair damaged railroads. Meantime, in October 1951, the North Koreans began to construct 3 new airfields within a few miles of each other at Saamcham, Taechon, and Namsi, all 50 to 70 miles north and northwest of Pyongyang. American B-29s attempted to destroy the newly constructed airfields. During the night of October 13 FEAF Bomber Command unsuccessfully raided the field at Saamcham. The Bomber Command staff subsequently planned daytime raids under the escort of F-84s and F-86s. The B-29s made successful raids on October 18, 21, and 22, damaging the landing strips and other facilities at all 3 airfields. However, on the 23rd MiG interceptors attacked the bombers and their escorts, shooting down 3 B29s and an F-84, while losing 4 MiGs. The B-29s returned to night raids but failed to destroy the North Korean airfields, and the MiG pilots flying from these fields continued to intercept and shoot down UN aircraft. On November 12, 1951, truce negotiations resumed at a new site--Panmunjom--and UN ground forces ceased all offensive action. By November 27 the UN had established defensive positions, and the Allies settled into a war of containment, although the Communists still pursued their effective air offensive. |

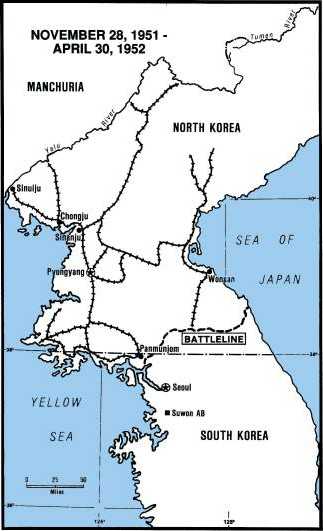

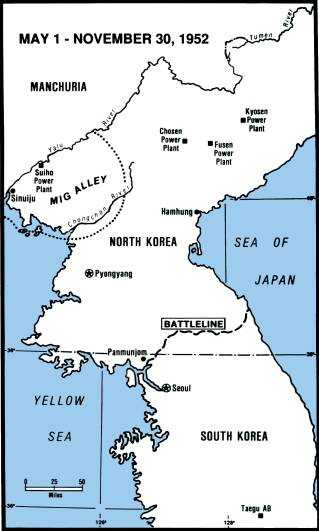

USAF offtcials recognized the need for more F-86s to counter the Chinese Air Force in Korea. The 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing at Suwon Airfield, 15 miles south of Seoul, consequently received F-86s from the United States to replace its F-80s. On December 1, 1951, the wing flew its first combat missions in the new Sabrejets. Members of the 51st and 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wings shattered the Communists' air offensive, downing 26 MiGs in 2 weeks, while losing only 6 F-86s. The Sabrejets achieved in the air the results that eluded the B-29s that bombed the enemy airfields near Pyongyang. For the rest of the winter, the MiG pilots generally avoided aerial combat; nevertheless, Fifth Air Force pilots between January and April 1952 destroyed 127 Communist aircraft while losing only 9 in aerial combat. In spite of increasing vulnerability to flak damage, the Fifth Air Force continued its raids against railways. In January 1952 the FEAF Bomber Command's B-29s joined this interdiction campaign. Although the Communists managed to build up supply dumps in forward areas, the UN air forces damaged the railways enough to prevent the enemy from supporting a sustained major offensive. The interdiction missions also forced the North Koreans and Chinese to divert materiel and troops from the front lines to protect and repair the railways. As the ground began to thaw, between March 3 and 25, the Fifth Air Force bombed key railways, but with limited success. For example, on the 25th fighter-bombers attacked the railway between Chongju, on the west coast 60 miles northeast of Pyongyang, the North Korean capital, and Sinanju, 20 miles further to the southeast. This strike closed the railway line for only 5 days before the Communists repaired it. The B-29s were somewhat more successful during the last week in March, knocking out bridges at Pyongyang and Sinanju. Fifth Air Force continued the interdiction campaign through April while looking for more effective means to block North Korean transport systems. In the winter of 1951-1952, with the establishment of static battle lines, the need for close air support declined drastically. To use the potential fire power of the fighter-bombers, in January 1952 the UN commander alternated aerial bombardment of enemy positions on 1 day with artillery attacks of the same positions on the next day. The Chinese and North Korean troops merely dug deeper trenches and tunnels that were generally invulnerable to either air or artillery strikes. After a month the UN Commander, General Ridgway, ordered the strikes stopped. With peace talks at Panmunjom stalemated and ground battle lines static, on April 30 UN air commanders prepared a new strategy of military pressure against the enemy by attacking targets previously exempted or underexploited. |

The new UN strategy sought to increase military pressure on North Korea and thus force the Communist negotiators to temper their demands. In May 1952 the Fifth Air Force shifted from interdiction missions against transportation networks to attacks on North Korean supply depots and industrial targets. On May 8 UN fighter-bombers blasted a supply depot and a week later destroyed a vehicle repair factory at Tang-dong, a few miles north of Pyongyang. The Fifth Air Force, under a new Commander, Maj. Gen. Glen O. Barcus, also destroyed munitions factories and a steel-fabricating plant during May and June. Meanwhile, Gen. Mark W. Clark took over the United Nations Command. Beginning on June 23, U.S. Navy and Fifth Air Force units made coordinated attacks on the electric power complex at Sui-ho Dam, on the Yalu River near Sinuiju, followed by strikes against the Chosin, Fusen, and Kyosen power plants, all located midway between the Sea of Japan and the Manchurian border in northeastern Korea. The aerial reconnaissance function, always important in target selection, became indispensable to the strategy of increased aerial bombardment, since target planners sought the most lucrative targets. One inviting target was the capital city of Pyongyang. It remained unscathed until July 11, when aircraft of the Seventh Fleet, the 1st Marine Air Wing, the Fifth Air Force. the British Navy, and the Republic of Korea Air Force struck military targets there. That night, following day-long attacks, the Far East Air Forces Bomber Command sent a flight of B-29s to bomb 8 targets. Post-strike assessments of Pyongyang showed considerable damage inflicted to command posts, supply dumps, factories, barracks, antiaircraft gun sites, and railroad facilities. The North Koreans subsequently upgraded their antiaircraft defenses, forcing UN fighter-bombers and light bombers (B-26s) to sacrifice accuracy and bomb from higher altitudes. Allied air forces returned to Pyongyang again on August 29 and 30, destroying most of their assigned targets. In September the Fifth Air Force sent its aircraft against troop concentrations and barracks in northwest Korea while Bomber Command bombed similar targets near Hamhung in northeast Korea. Along the front lines, throughout the summer and fall of 1952, the FEAF joined the U.S. Navy and Marines to provide between 2,005 and 4,000 close air support sorties each month. For example, FEAF Bomber Command not only flew nighttime interdiction missions but also gave radar-directed close air support (10,000 or more meters from friendly positions) at night to front-line troops under Communist attack. During the daytime the Mustang (F-51) pilots flew preplanned and immediate close air support missions. The 315th Air Division also supported the ground forces, flying supplies and personnel into Korea and returning wounded, reassigned, and furloughed personnel to Japan. C-124s, more efficient on the long haul, carded personnel and cargo. C-47s provided tactical airlift to airfields near the front lines, and C-l 19s handled bulky cargo and airborne and airdrop operations. During the summer of 1952, the 4th and 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wings replaced many of their F-86Es with moditied F-86Fs. The new Sabre aircraft had more powerful engines and improved leading wing edges which allowed them to match the aerial combat performance of the MiG-15 jet fighters of the North Korean and Chinese air forces. Even though the Communists had built up their air order of battle, they still tended to restrict their flights to MiG Alley and often avoided aerial combat with the F-86 pilots. By August and September, however, MiG pilots showed more initiative, and aerial engagements occurred almost daily. Even though the Communist pilots improved their tactics and proficiency, U.S. pilots destroyed many more MiGs, achieving at the end of October a ratio of 8 enemy losses to every U.S. loss. The Communists, in spite of the pressure of the air campaign, remained stubborn in the truce talks. On October 8, 1952, the UN negotiators at Panmunjom recessed the talks because the Chinese would not agree to nonforced* repatriation of prisoners of war. As winter set in, UN forces in Korea remained mired in the stalemated conflict. *Only those POWs who wanted repatriation would return to Communist control. Many enemy POWs preferred to remain in South Korea, but the Communist authorities insisted that these POWs also be returned. |

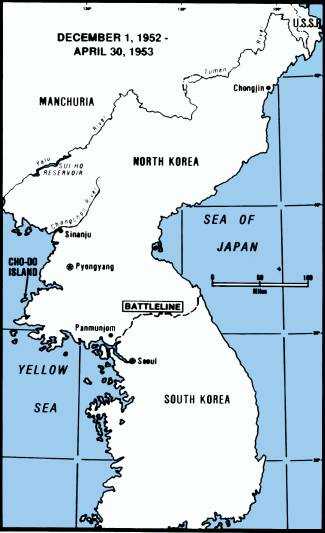

The military stalemate continued throughout the winter of 1952-1953. Allied Sabrejet pilots, meantime, persisted in destroying MiGs at a decidedly favorable ratio. In December the Communists developed an ambush tactic against F-86 pilots patroling along the Yalu River: MiG pilots would catch the UN aircraft as they ran short of fuel and headed south to return to base. During these engagements, some of the F-84 pilots exhausted their fuel and had IO bail out over Cho-do Island, 60 miles southwest of Pyongyang. United Nations forces held the island and maintained an air rescue detachment there for such emergencies. To avoid combat while low on fuel, Sabre pilots began to fly home over the Yellow Sea. MiG pilots at this time generally sought the advantages of altitude, speed, position, and numbers before engaging in aerial combat. The UN pilots, on the other hand, relied on their skills to achieve aerial victories, even though they were outnumbered and flying aircraft that did not quite match the flight capabilities of the MiG-15s. One memorable battle occurred on February l8, 1953, near the Sui-ho Reservoir on the Yalu River, 110 miles north of Pyongyang; 4 F-86Fs attacked 48 MiGs, shot down 2, and caused 2 others to crash while taking evasive action. All 4 U.S. aircraft returned safely to their base. While the Fifth Air Force maintained air superiority over North Korea during daylight hours, the Far East Air Forces Bomber Command on nighttime missions ran afoul of increasingly effective Communist interceptors. The aging B-29s relied on darkness and electronic jamming for protection from both interceptors and antiaircraft gunfire, but the Communists used spotter aircraft and searchlights to reveal bombers to enemy gun crews and fighter-interceptor pilots. As B-29 losses mounted in late 1952, the Bomber Command compressed bomber formations to shorten the time over targets and increase the effectiveness of electronic countermeasures. The Fifth Air Force joined the Navy and Marines to provide fighter escorts to intercept enemy aircraft before they could attack the B-29s. Bomber Command also restricted.missions along the Yalu to cloudy, dark nights because on clear nights contrails gave away the bombers' positions. FEAF lost no more B-29s after January 1953, although it continued its missions against industrial targets. On March 5 the B-29s penetrated deep into enemy territory to bomb a target at Chongjin in northeastern Korea, only 63 miles from the Soviet border. While Bomber Command struck industrial targets throughout North Korea during the winter of 1952-1953, the Fifth Air Force cooperated with the U.S. Navy's airmen in attacks on supplies, equipment, and troops near the from fines. In December l952 the Eighth Army moved its bombline from 10,000 to 3,000 meters from the front lines, enabling Fifth Air Force and naval fighter-bombers to target areas closer to American positions. Beyond the front lines, the Fifth Air Force focused on destroying railroads and bridges, allowing B-26s to bomb stalled vehicles. In January 1953 the Fifth Air Force attempted to cut the 5 railroad bridges over the Chongchon Estoary near Sinanju, 40 miles north of Pyongyang. Expecting trains to back up in marshaling yards at Sinanju, Bomber Command sent B-29s at night to bomb them, but these operations hindered enemy transportation only briefly. As the ground thawed in the spring, however, the Communist forces had greater difficulty moving supplies and reinforcements in the face of the Fifth Air Force's relentless attacks on transportation. At the end of March 1953, the Chinese Communist government indicated its willingness to exchange injured and ill prisoners of war and discuss terms for a cease-fire in Korea. On April 20 Communist and United Nations officials began an exchange of POWs, and 6 days later, resumed the sessions at Panmunjom. |

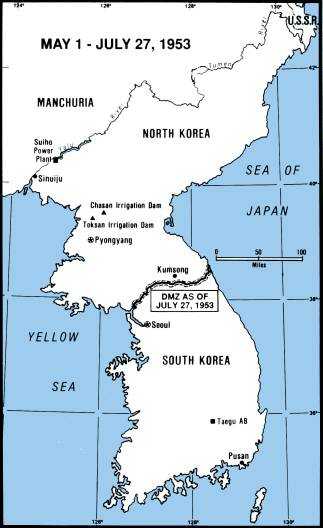

Although Communist leaders showed a desire to negotiate an armistice, they would not do so before trying to improve their military positions. During May 1953 Fifth Air Force reconnaissance revealed that the Chinese and North Koreans were regrouping their front-line forces. On the last day of the month, Lt. Gen. Samuel E. Anderson took command of the Fifth Air Force. Communist forces directed a major assault on June 10 against the Republic of Korea's II Corps near Kumsong, a small town in central Korea, 110 miles southeast of Pyongyang. With American aid, the South Koreans stopped the Communist drive by June 19 with little loss of territory. During the enemy offensive, UN pilots broke previous records in flying close air support sorties, with Far East Air Forces flying 7,032, the Marines, 1,348, and other UN air forces, 537. Also during June FEAF devoted about 1/2 of its combat sorties to close air support. Communist troops attacked again in central Korea on July 13, forcing the ROK II Corps to retreat once more. But by the 20th Allied ground forces had stopped the foe's advance only a few miles south of previous battle lines. Once again, during July, FEAF devoted more than 40 percent of its 12,000 combat sorties to close air support missions. During the Communist offensives, the 315th Air Division responded to demands of the Eighth Army and between June 21 and 23 airlifted an Army regiment (3,252 soldiers and 1,770 tons of cargo) from Japan to Korea. From June 28 through July 2, the airlifters flew almost 4,000 more troops and over 1,200 tons of cargo from Misawa and Tachikawa Air Bases in Japan to Pusan and Taegu airfields in Korea. These proved to be the last major airlift operations of the Korean conflict. In aerial combat, meanwhile, Fifth Air Force interceptors set new records. Sabrejet pilots fought most aerial battles in May, June, and July 1953 at 20,000-40,000 feet in altitude, where the F-86F was most lethal, and during these 3 months, claimed 165 aerial victories against only 3 losses-the best quarterly victory-loss ratio of the war. Fifth Air Force and FEAF Bomber Command also continued to punish the enemy through air interdiction, making attacks on the Sui-ho power complex and other industrial and military targets along the Yalu River. In addition, the Fifth Air Force in May attacked irrigation dams that had previously been excluded from the list of approved targets. On May 13 U.S. fighter-bombers broke the Toksan Dam about 20 miles north of Pyongyang, and on the 16th they bombed the Chasan Dam, a few miles to the east of Toksan Dam. The resulting floods extensively damaged rice fields, buildings, bridges, and roads. Most importantly, 2 main rail lines were disabled for several days. Between July 20 and 27 the UN Command bombed North Korean airfields to prevent extensive aerial reinforcement before the armistice ending the Korean conflict became effective on July 27, 1953. |

|

Korean Service MedalA gateway encircled with the inscription KOREAN SERVICE is embossed in the center of the obverse side of the Korean Service Medal. Centered on the reverse side is the Korean symbol that represents the unity of all beings, as it appears on the national flag of the Republic of Korea. Encircling this symbol is the inscription UNlTED STATES OF AMERICA. A spray of oak and laurel graces the bottom edge. The medal is worn with a suspension ribbon, although a ribbon bar may be worn instead. Both the suspension ribbon and ribbon bar are blue, representing the United Nations, with a narrow, white stripe on each edge and a white band in the center. Executive Order No. 10179, November 8, 1950, established the Korean Service Medal. A member of the U.S. Armed Forces earned the medal if he or she participated in combat or served with a combat or service unit in the Korean Theater on permanent assignment or on temporary duty for 30 consecutive or 60 nonconsecutive days anytime between June 27.1950, and July 27, 1954. Service with a unit or headquarters stationed outside the theater but directly supporting Korean military operations also entitled a person to this medal. An individual also received a Bronze Service Star for each campaign in which he or she participated, or a Silver Service Star in place of 5 Bronze Stars. These stars are worn on the suspension ribbon or the ribbon bar. Service members who participated in at least 1 airborne or amphibious assault landings are entitled to wear an arrowhead on the ribbon or ribbon bar. |

Korean Service StreamerThe Korean Service Streamer is identical to the ribbon in design and color. Air Force units received a service streamer if they were based in Korea between June 27, 1950 and July 27, 1954, or based in adjacent areas of Japan and Okinawa, where they actively supported other units engaged in combat operations. A campaign streamer is a service streamer with the name and dates of the campaign embroidered on it. A unit received a campaign streamer instead of a service streamer if it served in, or flew combat missions into, the combat zone during a particular campaign. Units participating in amphibious or airborne assault landings received the campaign streamer with an embroidered arrowhead preceding the name and dates. |

|