Try Amazon Audible Plus

Amazon Audible Gift Memberships

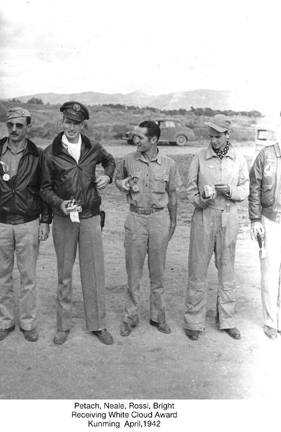

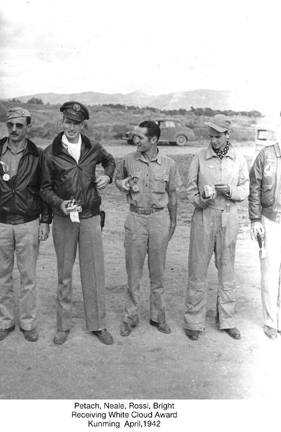

A Flying Tiger's Story by Dick Rossi. Part two.

A Flying Tiger's Story by Dick Rossi. Part two.

Continued:

Their transmitter was out of commission at the base causing communication problems but they were

able to monitor some of the other AVG transmissions so we learned that the flight of seven had only

made it as far as Lashio due to strong headwinds. Because there was some maintenance required, they

would stay overnight and go on to Rangoon in the morning.

Having their proposed take-off time and figuring they would give our old base a "buzz job," (which

I later found out they did) I planned to join them for the trip to Rangoon. When they had not

arrived after I had sat at the end of the runway for five minutes with my engine starting to

overheat, I took off for Rangoon. I had just taxied to a parking spot at Mingaladon when they

arrived. They had given me up for lost so were a bit shocked to see me there on the welcoming

committee.

After a bombing raid that night and a couple of intercept flights which turned out to be false

alarms, I was scheduled to go on an escort mission on the morning of 19 January. Frank Lawler and I,

along with two RAF pilots in Brewster Buffaloes, were to escort three RAF Blenheim bombers across

the Gulf of Martabon to Tavoy. We were to fly cover for the bombers as they went in to evacuate some

British personnel. One RAF fighter and Lawler were flying on the left side of the bomber formation

and the other RAF fighter and I were on the right side in an open formation.

More than halfway across the gulf the haze suddenly turned to fog and I lost sight of all the other

planes. We were flying at 2,500 feet, so I just held my course and altitude, checking my ETA for the

coast. Very soon I emerged from the fog bank and came out into bright sunlight with the coast a

short distance ahead, the RAF plane to my left was just a short distance ahead, but there were no

other planes in sight. I joined up on the RAF fighter and proceeded directly to the airport at

Tavoy. On reaching the airfield, we dropped down to 1,000 feet and started to circle the field on

opposite sides to await the others.

We had been there about five minutes and I was heading on a leg toward the coast with the RAF pilot

flying in the opposite direction on the other side of the field, when straight ahead I saw six

bombers suddenly appear over the hills just a little north along the coast heading for the airfield.

Since we had been escorting only three I had to assume they were the enemy. The RAF pilot was flying

with his back to them, so I immediately spun across to alert him and at the same time turned on my

gunsight and switches, then pulled around to attack the bombers. That’s when I got my first sight of

a Japanese fighter (red ball and all) as he passed directly underneath me. He had made a run on me

but did no damage. At the same time I saw a fighter with a red ball on its side making a vertical

dive on the bombers. That meant that the bombers were RAF and we were being attacked by Japanese

fighters.

What had happened up to this point was that the RAF had sent an additional three Blenheims on the

mission; they had made a course change slightly to the north and joined up with our three and all

were proceeding to Tavoy. Unknown to us was that the Japanese had captured the airfield during the

night. All the Blenheim bombers dove out to the coast and into the fog bank and returned to

Mingaladon.

I turned my attention to the fighter that had attacked me. He did a quick 180° turn and we were

closing head-on. He dove underneath me and I could not get a bead on him. He immediately flipped

over on my tail, but with my high speed I had plenty of room to go out and do a fast 180° turn and

come back for another pass. I saw the RAF fighter as I came around for another head-on pass. I

figured if I went into his area, he could pick the enemy plane off my tail. I concentrated on the

Japanese plane and we made the same maneuvers once again. When I turned around for another pass I

was pretty much into the morning sun. I figured that if I started firing real early, he would have

to fly through my line of fire to dive under me. All of this action was taking place at about 1,500

feet, so there was a limit on how low he could dive. Once again he dove under me and I used my speed

to get some distance between us. As I started to turn around for another attack I saw smoking

tracers all around me. The Japanese fighter had maneuvered me into the trap I had tried with the RAF

plane. I never did know if there were more than two fighters in the ambush and I never saw the plane

I had been fighting against after that pass. I then immediately put my nose down and headed for the

fog bank over the beach.

I leveled off at about 300 feet, flew for a couple of miles and then started to climb for altitude.

I was low on fuel and almost out of ammunition and knew I could not get back to Rangoon safely.

Knowing the RAF had a field north at Moulmein, I headed in that direction and climbed to 15,000

feet. Soon I saw the field at Moulmein and was about to start my descent when I saw four fighters

approaching. I was reluctant to lose my altitude but I was almost out of gas and very low on

ammunition. As they got closer I was able to recognize them as P-40s (much to my relief).

I leveled off at about 300 feet, flew for a couple of miles and then started to climb for altitude.

I was low on fuel and almost out of ammunition and knew I could not get back to Rangoon safely.

Knowing the RAF had a field north at Moulmein, I headed in that direction and climbed to 15,000

feet. Soon I saw the field at Moulmein and was about to start my descent when I saw four fighters

approaching. I was reluctant to lose my altitude but I was almost out of gas and very low on

ammunition. As they got closer I was able to recognize them as P-40s (much to my relief).

I quickly landed at Moulmein and started to refuel for the return to Rangoon. The gasoline had to

be filtered through a chamois, so it was about a two-hour process. I had two bullet holes through my

propeller but didn’t find any other damage.

At Moulmein I saw the second RAF fighter from our original mission. He had climbed to 4,000 feet

with Lawler after hitting the fog bank and had come over Tavoy at that altitude. He was engaged in

some skirmishes at that altitude and did not see Lawler again. He was unaware that the first RAF

pilot and myself were engaged below with the Japanese planes. He and the Japanese had broken off

contact but his aircraft had a bullet through his oil tank and the falling pressure sent him

scrambling for Moulmein.

While the RAF people were refueling our two planes we did a few repair jobs. I filed off the rough,

splintered metal on my prop (which had been caused by my own 50 cal. gun) and the RAF pilot plugged

up the hole in his oil tank. He fashioned a plug out of a tree branch, wrapped it with some cloth

and used it to plug up the hole. We tied strips of rags around the tank to hold the plug in place.

Rather than fly directly across the gulf to Rangoon, the RAF pilot wanted to follow the northern

shore in case the oil tank repair did not hold up and he would have to make an emergency landing. He

asked me to fly along side him so I could report his position if this should happen. Luckily, it

held up and we arrived at Mingaladon without any problems but several hours late, causing an air

raid alarm.

Since I arrived back hours after my normal gas supply would have been exhausted, I was reported

lost to Chennault. My fellow squadron mates laughed that they had already divided up my belongings!

The next day they were changing the prop on my shot-up #18 and I had a day off. Robert "Moose" Moss

had to bail out near Moulmein but was reported to have arrived at the field okay. We also heard via

Japanese radio that Charlie Mott, who was shot down in a strafing raid, had been captured. He was

the first AVG POW.

On the 21st of January, I went on an escort mission to Tak, about a 400 mile round trip. We had our

fighter planes at several altitudes but met no enemy aircraft. We ran several more escort missions,

which finally managed to stir up the Japanese.

A pattern developed where each time we went over and hit their fields, we would be in for a series

of attacks. Taking off so many times a day for many days seemed to make it all blend into a blur of

action, false alarms and real alarms throughout the day, one scramble after another, one fight after

another.

On 25 January, Chennault sent the 1st Squadron Leader, Sandell, down from Kunming to our base at

Mingaladon with twelve more pilots and planes. They arrived about dusk and we were glad to see the

new arrivals. The RAF was also bringing some more Hawker Hurricane fighters to Mingaladon. All this

raised our morale. Unfortunately, the next day during another big fight, we lost "Cokey" Hoffman. He

was a former enlisted Navy pilot and our oldest and most experienced pilot. We all felt the loss

deeply.

The rest of the month continued with the fast paced action interspersed with annoying night raids.

The night raids were an irritation and sleep interruption problem but did little actual damage and

lost them a few of their planes in the process. On the first of February the Japanese were in

control of Moulmein, having taken it during the night. That meant we lost another outlying field to

use for emergencies and refueling.

In Kunming we had a lot of trouble with our Squadron Leader, Sandell. Some of the members had gone

to Chennault to see about having him removed. The "Old Man" did not remove him but gave him a good

"chewing out." But with Sandell and most of the 1st Squadron in Rangoon, Sandell seemed to be a

changed man. After his first combat encounters with real bullets and a couple of victories, he

became downright likeable.

In one of our bigger battles on 28 January, I was flying Charlie Bond’s plane, #5. He was a little

piqued when I brought it back with a few bullet holes, the antenna shot off and one rudder cable

severed. I was perfectly satisfied to get down in one piece. It did not take our ground crew long to

have the plane ready to go again.

On 3 February, Chennault ordered the 2nd Squadron to start moving back to Kunming from Rangoon.

They started moving out a couple of days later and the rest of the 1st Squadron started to arrive in

Rangoon. During these few nights we had consistent night bombings by the Japanese. They scored some

good hits on the airfield and in the residential area, where most of our pilots were living. No one

was hurt but a couple of people were knocked out of bed by the bomb explosions. We had become lax

about heading for the air raid trenches so this served as a good wake up call to us.

The early raids on Mingaladon had knocked out the barracks on the field and damaged all the

buildings. The RAF took care of our billeting and put us up with local British residents. We had

breakfast and dinner with our hosts for which the RAF compensated them.

By 7 February the last of our 1st Squadron was in Rangoon and the last of the 2nd Squadron left

Rangoon for Kunming on the 8th. We were glad to see all the fellows now in Rangoon but it was a bad

day for us. Sandell was up testing his plane when it dove into the ground, killing him. He had

already shot down five planes to become an Ace and was doing a good job running the squadron. His

plane had been shot up a bit in a previous engagement and he had made a forced landing on the

airfield. A Japanese pilot followed him down and tried to make him crash. However, it was the

Japanese plane and pilot that were strewn all over the landscape, but he did manage to ruin the

empennage of Sandy’s plane. It had been repaired and Sandy was giving it a test hop.

Sunday the 8th was my day off and I was a pall barer for Sandell. With our small group these losses

hit us pretty hard. Chennault immediately wired down orders making Bob Neale our squadron leader and

Pappy Boyington the vice squadron leader. The 1st Squadron was now the representative of the AVG in

Rangoon.

Sunday the 8th was my day off and I was a pall barer for Sandell. With our small group these losses

hit us pretty hard. Chennault immediately wired down orders making Bob Neale our squadron leader and

Pappy Boyington the vice squadron leader. The 1st Squadron was now the representative of the AVG in

Rangoon.

With the fall of Moulmein, and the Japanese army advancing on Rangoon, many of the civilians were

evacuating to India. There was a lull in the Japanese day attacks and we flew quite a few bomber

escort missions, with no enemy aerial contact. But the Japanese ground forces kept advancing. Our

big worry now was how we would get our ground people out if the enemy cut the Burma Road north of

Rangoon. There were so many rumors flying around that we did not know what to expect.

We got the news that Singapore had fallen on 16 February and the Japanese would now be able to

concentrate their attacks on Rangoon. We were flying a lot of escort missions to aid the front line

Chinese troops, but did not seem to be accomplishing much. We heard rumors that the Japanese would

be parachuting into Rangoon. On the 20th, all the civilians were given orders to evacuate within

forty-eight hours. The exodus was really getting under way.

On 22 February we were told to be ready to leave on an hour’s notice. Our baggage had been sent up

the Burma Road and our unit had been reduced to a skeleton ground crew. Then came a revision to the

order saying we should be prepared to leave on a twelve hour notice. A couple of our pilots were

ordered to go up to Magwe to be able to fly patrols to protect our ground convoys.

The British had begun burning supplies on the docks and in the warehouses so they would not be

captured. The bombers were leaving and all criminals, the insane and lepers were released. They

could be seen wandering around the city in a daze. The Japanese sympathizers were getting bolder and

even firing on British officers. It was crazy and dangerous. Our food consisted mainly of whatever

canned goods could be gathered from abandoned stores and warehouses.

On the 24th we were told to hold Rangoon at all costs. With the new orders, Chinese soldiers were

sent to town to shoot all looters. We were told to increase our strafing missions and search out

enemy ground forces.

The future looked dismal due to the lack of spare tires and a dwindling oxygen supply. Our strafing

raids aroused the Japanese Air Force, and their attacks on Rangoon were renewed with a vengeance.

Communications had really deteriorated and when we received any, they were usually mixed up.

Climbing out on an alert, my flight leader Ed Liebolt, motioned for me to keep climbing and that he

was descending. We were at about 11,000 feet and I assumed he had failed to turn on his oxygen. It

had to be turned on in the baggage compartment before takeoff. He disappeared and was never seen

again. That day, the Japanese Air Force sent wave after wave against Rangoon. Between the AVG and

the RAF, we gave them a pretty hard time of it. We then received word that we would be relieved on

the first of March.

On 26 February, Bob Neale planned a morning strafing raid on Moulmein. He believed the Japanese

would be staging there because of all the sorties they were sending against us. Eight planes were to

go on the mission. Before we could take off we received an alert that "bandits" were inbound. We

scrambled, but one plane had trouble and did not get off. We climbed to 18,000 feet but it was a

false alarm. So Bob Neale decided to go on the previously planned mission. I was flying on Bob’s

wing and since George Burgard’s wingman did not get off, he joined up with us.

As we approached Moulmein we dove down to a low altitude and got below the level of the hills and

approached from the south. At an auxiliary field a few miles from Moulmein we saw two planes sitting

on the ground, which we set afire and pulled up over the hill to Moulmein. We made an attack on the

field just as three Japanese fighters were getting airborne. I shot down the leader of the three and

swung around to come back as others were taking off. I shot down another head-on and saw a Japanese

plane flying toward me on a collision course. I pushed over violently and headed for the water. I

was at 1,500 feet and leveled off at about 20 feet, only to see that I was heading for a ferry boat

carrying troops. I was able to get in a burst with all six guns from about 200 yards before pulling

up over the boat. Enemy troops were diving off the sides as I flew over. As I was turning around to

see what damage took place, I noticed two fighters heading south. Thinking they were heading for

their field in Tavoy, I gave chase hoping to sneak up on them, but after five minutes I was able to

identify them as British Hurricanes. I checked my fuel and ammunition and headed back to Mingaladon.

After refueling and rearming, Charlie Bond and I went out to see if we could find any sign of Ed

Liebolt. We searched for an hour with no results. As we were preparing to land we saw all our planes

starting to take off. By the time we got our altitude the bombers were pretty far east, high-tailing

it for home. Fritz Wolf and I found a small cluster of fighters east of the field and went after

them. I shot one, which burst into flames and then raked another from the side, but it went by so

fast I did not see what happened to him. Some of my guns had quit firing so I pulled up for altitude

to clear the gun jams. Then we got a call to land for fuel and ammunition as they wanted to keep us

as ready as possible. Later that afternoon we went back over Moulmein and found that the Japanese

had deserted it.

Continued in Part Three.

A Flying Tiger's Story, Part One

Return To Main Page

All text and images Copyright © J.R. Rossi 1995.

Reproduction for distribution, or posting to a public forum without express

written permission is a violation of applicable copyright law.