Try Amazon Audible Premium Plus and Get Up to Two Free Audiobooks

Amazon Audible Gift Memberships

A Flying Tiger's Story by Dick Rossi. Part three.

A Flying Tiger's Story by Dick Rossi. Part three.

Continued:

Our living accommodations in Rangoon had deteriorated so most of the pilots had moved out to the

"18 mile farm" where our ground crews were staying. We had a fried chicken dinner and went to bed,

but there was a lot of night bombing going on at Rangoon.

At 0200, Neale informed us that the Japanese had closed the Burma Road south of Toungoo and that

the RAF had evacuated the radio detection finder, so we would not be getting any more warnings. He

said he was going to try to get our ground crews out via the Prome Road, the last route of escape.

Because of the night bombings, we always dispersed our flyable P-40s to the outlying fields as a

way to protect them. There was one plane at Mingaladon, #78, that was badly shot up, but it was

repairable. Harry Fox and his crew went to Mingaladon to fix it. They were back by sunup to tell us

it was ready to go. Bob Neale took me to the field in the squadron station wagon. Sure enough, Fox

and his crew had the P-40 back in flyable condition. It had taken a shrapnel hit, but was otherwise

okay. I took off in it, the last AVG plane to leave Mingaladon, and flew over to our dispersal

field. About the time we finished refueling, we heard Japanese bombers approaching.

Because of the night bombings, we always dispersed our flyable P-40s to the outlying fields as a

way to protect them. There was one plane at Mingaladon, #78, that was badly shot up, but it was

repairable. Harry Fox and his crew went to Mingaladon to fix it. They were back by sunup to tell us

it was ready to go. Bob Neale took me to the field in the squadron station wagon. Sure enough, Fox

and his crew had the P-40 back in flyable condition. It had taken a shrapnel hit, but was otherwise

okay. I took off in it, the last AVG plane to leave Mingaladon, and flew over to our dispersal

field. About the time we finished refueling, we heard Japanese bombers approaching.

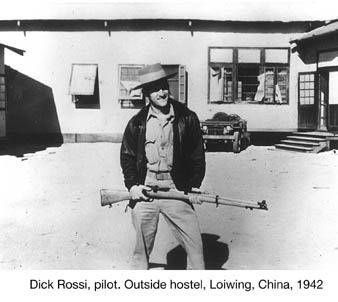

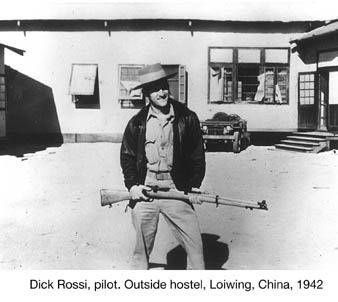

As preplanned, our flight of six P-40s immediately took off for Loiwing with Bob Little leading.

Others went to different bases. Little got lost but Fritz Wolf took over and we finally landed at

Lashio. Bob Prescott was down to four gallons of gas. After refueling, having lunch and a beer, we

took off for Loiwing.

As preplanned, our flight of six P-40s immediately took off for Loiwing with Bob Little leading.

Others went to different bases. Little got lost but Fritz Wolf took over and we finally landed at

Lashio. Bob Prescott was down to four gallons of gas. After refueling, having lunch and a beer, we

took off for Loiwing.

We were out of oil, oxygen and Prestone leaving Rangoon. I was low on Prestone leaving Lashio and

my engine overheated and began to backfire, then it cut out. The terrain was too rough for an

emergency landing so I started to bail out. As I put my leg out of the cockpit the engine caught on,

so back in the seat I went. This routine happened one more time until I caught sight of the Loiwing

field in the distance. Easing the power and starting a slow descent, I was able to reach the field

safely.

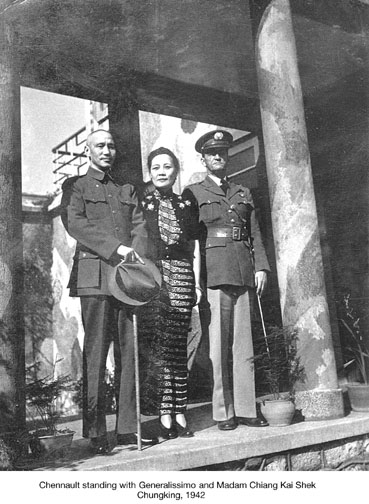

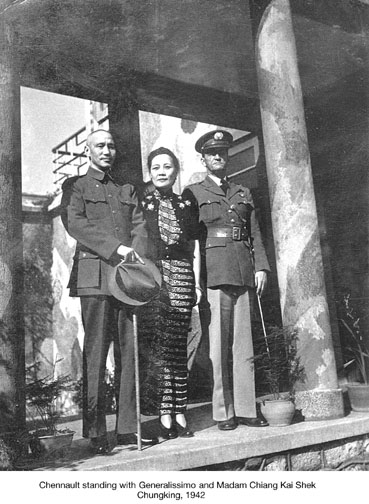

After two days at Loiwing with no action and one standby (because Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek was

at a meeting in Lashio), we were ordered to Kunming. We arrived without incident, to be

congratulated by Chennault. Both he and Harvey Greenlaw told us to rest, so we had one day off!

Arvid Olson’s 3rd Squadron had now gone to Magwe to take over the defense there. Five of their

squadron pilots had left for Magwe, got lost and cracked up their aircraft in emergency landings.

Two aircraft could be repaired to fly out. They wanted more planes at Magwe so Prescott, Wolf and I

requested to fly the planes there and then to stay in Magwe so that we could be where the action

was.

Arvid Olson’s 3rd Squadron had now gone to Magwe to take over the defense there. Five of their

squadron pilots had left for Magwe, got lost and cracked up their aircraft in emergency landings.

Two aircraft could be repaired to fly out. They wanted more planes at Magwe so Prescott, Wolf and I

requested to fly the planes there and then to stay in Magwe so that we could be where the action

was.

The final decision was to send three P-40s with Olson, Prescott and Wolf to Magwe, and Frank Swartz

and I would go there in an Army C-47 with our ground crew and all their tools. That turned out to be

one of the wildest rides I had ever had.

The pilot in command of the C-47 was ill, so they recruited a Chinese pilot. Harold Chinn from CNAC

was to ride as copilot for the newly promoted Army captain second-in-command. The plane had been

stripped - there were no seats, no safety belts and heavy toolboxes sitting all over the deck. All

of us passengers were sitting on the deck.

The C-47 was three quarters of the way down the field and the tail was still on the ground. We all

edged up toward the front to lighten the tail. We ran out of airstrip and began bouncing along the

rough ground before we finally made it into the air at a very slow speed. The plane got up to about

twenty feet and we felt a lurch as the plane passed over some trees about fifty feet tall. Then came

the horrible feeling as the plane was mushing toward the ground. We saw one wing suddenly raise and

a house passed under it.

We later found out that the Chinese army co-pilot flying the ship had just graduated from cadet

school and had only two landings in the C-47. The CNAC pilot, Chinn, had taken over the controls as

we ran out of field. Slowly we gained about 1,500 feet altitude above the ground (airfield was at

6,500 feet), but could not gain enough altitude to get over the west mountain. They were trying to

fly around it and fly in the valleys. We went up to the cockpit and said we all wanted to go back to

Kunming. The starboard engine was vibrating badly and throwing oil. They returned to Kunming and got

the plane on the ground and we happily disembarked.

The next day Swartz and I, with our eighteen ground crew, boarded a CNAC DC-3 flown by H. L."Woody"

Woods, an experienced Pan Am and CNAC pilot. We proceeded to Magwe via Lashio. The next day Woody

took the rest of the 1st Squadron back to Kunming.

On 13 March, three B-17s came in to evacuate women and children. One of the navigators was a fellow

named Svaboda who had washed out of Pensacola while I was instructing there. What a place to meet.

The next day I went on a strafing mission near Kyaikto with the 3rd Squadron Leader, Arvid Olsen. We

stopped at Toungoo for refueling and lunch on the way back.

For the next week I had alternating days of strafing missions. The 21st was a bad day. It started

out fine with the British sending nine Blenheims with Hurricane escort to Mingaladon where they did

a lot of damage to the enemy and shot down eight fighters. We were listening to their story when we

got an alert. I was flying #38 and its starter was out, so I was late getting off. It was a false

alarm. I was relieved for lunch by Frank Swartz and as we were returning to the field, we found our

planes taking off. By the time we reached the alert tent they were all in the air except for #38. We

called operations and were told the enemy was approaching from the southeast. Swartz had decided #38

was not fit to fly.

With Fritz Wolf’s help we hunted up a screwdriver and crank. Crew Chief John Fauth came to help and

we cranked up #38. Almost everyone else had already evacuated the field. I took off, but with

multiple layers of scattered clouds and haze, I was unable to see any of our P-40s. I guessed that

the enemy was now nearby and climbed for altitude northeast of the field. As I reached 23,000 feet

our radio announced that Japanese were strafing the town and field.

I came rushing down to 2,000 feet to get under the clouds, circled the town and field and did not

see another plane. I could see that the field had been hit hard by bombs. There were fires burning

and one Hurricane on the ground was on fire.

I then headed south thinking I might find some enemy aircraft. After about ten minutes and not

seeing anything, I figured it would be best to get back to the field in case anymore Japanese

aircraft showed up. In that lapsed time they came again hitting the field, buildings and several of

the Blenheims. More fires were burning.

With all the clouds and haze, they did a surprisingly good job of hitting our field. There were

twenty-seven bombers in each wave plus about forty fighters. Almost one hundred enemy planes had

come over, I had been in the air for almost two hours and I had not made contact. It was very

frustrating.

The pilots who did make contact said the Japanese planes were all faster than those they had met

before; no fixed landing gear fighters either. Ken Jernstedt was shot down but only slightly

injured. It was one of our worst engagements. We destroyed only a few of them.

Several of our people were hurt by bombs. Swartz had part of his hand blown off and a bad gash in

his throat. Two crew chiefs were injured. Will Seiple had a lung caved in from bomb concussion as he

lay on the ground. John Fauth had most of his right shoulder and part of his face blown off.

The next day was to be my day off, so I sat up most the the night with the injured. Part of the

time I had to hold a flashlight as "Doc" Richards worked on Fauth. He had already bandaged up

Swartz. Fauth was really in bad shape. Prescott and I rotated between the two rooms where Swartz and

Seiple were, and where Doc was working on Fauth. They were all conscious and suffering badly. I had

known Swartz from cadet days when we were both editors on the cadet yearbook at Pensacola. Listening

to them and trying to console them as they suffered, and watching Doc work on Fauth made me feel

terrible. I was sure I never wanted to be a doctor. That was the worst night of my life. About 0430

Fauth died.

The next morning I was washing up about 0830 when I heard someone yell, "Here they come!" We had no

warning and none of our planes got off. There were twenty-two bombers and a swarm of fighters. They

really blew the hell out of our planes with their bombing and strafing. Luckily, all of our people

got safely off the field.

About noon we got Swartz and Seiple on a DC-3 going to Calcutta. About ten minutes after they left

another wave of enemy planes came over. There were fifty-three bombers and another swarm of

fighters. Our warning system was non-existent, so everybody tried to stay clear of the field. After

a reasonable wait, we ventured back to the airfield. Old #38 was as full of holes as a sieve, but

did not burn. Some P-40s were burned right down to the ground. All of the Blenheims were destroyed.

We prepared to evacuate to Loiwing. Ed Overend and I each had a jeep and planned to travel

together. The crew chiefs figured they could make four P-40s flyable and worked at the field that

night with flashlights. Ed and I got up at 0330, had coffee and prepared to leave. Some of those

driving had already left during the night. And, sure enough, the crew chiefs had four planes ready

to fly. At 0430 we shoved off - destination Loiwing. We were on our own.

That afternoon we met up with Arvid Olsen and Parker Dupouy outside of Maymyo and sought out

sleeping quarters. We ended up at the headquarters of the American Military Mission. There we found

two reporters, Daniel DeLuce and Mr. Berrigan. Army Captain Jones was very helpful. I lucked out in

a coin toss with Overend and got to sleep on a Simmons mattress out on the porch of the quarters.

That afternoon we met up with Arvid Olsen and Parker Dupouy outside of Maymyo and sought out

sleeping quarters. We ended up at the headquarters of the American Military Mission. There we found

two reporters, Daniel DeLuce and Mr. Berrigan. Army Captain Jones was very helpful. I lucked out in

a coin toss with Overend and got to sleep on a Simmons mattress out on the porch of the quarters.

The next morning we arose and had breakfast with General Stilwell. We told him how to win the war,

but we’re not sure how much he listened. He didn’t have much to say. Ed Overend knew a missionary

family there and they gave us a gallon of fresh strawberries to take on our trip. That was a memorable treat.

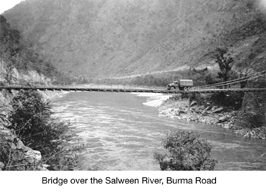

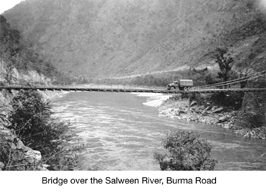

We drove in our jeeps for the next three days, up the Burma Road to Loiwing. It was an interesting

and sometimes thrilling three days. There were washouts, hairpin turns, all kinds of logistical

problems, food problems, fuel problems, but a great adventure. There were no planes at Loiwing, but

eight 3rd Squadron planes came in the next day, so we were then back on schedule.

During the next several days Chuck Older shot down a Japanese observation plane and "Fearless

Freddie" Hodges got married. We had a nice party for the bride and groom and even the Japanese

joined the celebration, in that we had an alert in the middle of the party and we all ran for the

slit trenches. Fortunately the Japanese never showed over the field, so we continued with the party.

During the next several days Chuck Older shot down a Japanese observation plane and "Fearless

Freddie" Hodges got married. We had a nice party for the bride and groom and even the Japanese

joined the celebration, in that we had an alert in the middle of the party and we all ran for the

slit trenches. Fortunately the Japanese never showed over the field, so we continued with the party.

On 8 April, in the morning, the Japanese sent an observation plane over. Then at about 1300,

thirteen fighters arrived on a strafing raid. Just before they arrived, a Blenheim had landed and

two P-40Es were brought in by Pan Am ferry pilots (one of the pilots named Dukelow had been in my

cadet class at Pensacola). Our P-40E and the Blenheim were shot up and the other P-40E was burned to

the ground.

It was my day off so I watched the attack from a slit trench. Our flyable P-40s had taken off and

climbed to about 22,000 feet. The Japanese came in low and were having a real picnic shooting up the

field when our gang pounced on them. Three new P-40Es flown by Olsen, Ken Jernstedt and Robert

Little happened to arrive from Kunming at the same time and joined the action.

I was in the slit trench with Doc Richards and saw two Japanese planes fall in flames fairly close

and two more go down a little further away. The fighters were the Zekes, very similar to the Zero.

We got seven of them and did not lose any of our own aircraft in the air. The next evening ten

planes of the 2nd Squadron arrived to join us. Then Chennault came in from Kunming to stay for a

while.

On 10 April, as the alert crew was on its way to the field, I saw five Japanese fighters diving for

the field. Some of the crew chiefs were sitting in the planes warming them up. We had about twenty

four planes all lined up like sitting ducks and they made run after run on them. Two of our crew

chiefs were in their planes as they were hit but luckily there were no injuries to our men as they

all dove for the slit trenches. Despite having lots of time and no opposition, the Japanese only

damaged nine of the twenty-four planes. Four of the nine were patched up and ready to fly in about

an hour, the rest were repaired later. The Japanese were back that afternoon with seven fighters but

we wiped out five of them on that mission.

We had been flying regular patrols over the front lines to boost the moral of the Chinese ground

troops. Bob Prescott and I got orders to go back to Kunming on the 20th. About thirty minutes after

we took off, we were contacted by radio and recalled. Prescott was then sent up in the Group

Beechcraft and I was told to wait for another P-40 that was being repaired. The next day I flew #59

up to Kunming which was an enjoyable trip. I followed the Burma Road all the way, sighting a couple

of airfields. The next day I was back on alert duty.

Kunming was quiet on 26 April, and I was at the hospital visiting Bob Brouk who had been strafed

while making an emergency landing at Nam Sang in Burma. He was hit in the thumb and leg. While

visiting, I received a call from George Burgard to get back immediately as we were to leave on a

CNAC plane at once. Burgard, Jim Cross and I were to go to Karachi, meet with thirteen Chinese

pilots from the CAF, and ferry sixteen P-43s back to Kunming.

We gathered some baggage and boarded a CNAC plane for Calcutta, but were forced to return because

of bad weather. We left the next day and had a very turbulent flight to Calcutta, but we didn’t mind

because this was great R & R for us. We waited three days in Calcutta for a BOAC flying boat to

Karachi.

We had to test fly and put slow time in on all of the P-43s. Eddie Goyette was checking out the

Chinese pilots. After the usual delays and a great vacation, we left Karachi on 11 May. We were each

leading a group of four, the fourth leader was a Chinese pilot, Y.T. Low. The trip to Kunming was

filled with problems including bad weather just about all the way. We had to turn around several

times but finally got to Dinjan, the last stop before crossing the "Hump" (Himalayas) into China.

The trouble took its toll and our flight was down from sixteen planes to ten. We remained overnight

there and Doolittle’s men came through on their way back to the States. They had had a really rough

time. The next day the ten of us took off for Kunming. The weather was terrible but we climbed on

top and flew over a solid overcast for more than 400 miles. Just short of Kunming the weather

cleared and Burgard led us in a screaming dive for the airport. As our flight of ten cleared the

hills west of the airfield, we caused a panic at the field. They had no word of our arrival and

those P-43 radial engines made us look like Japanese planes.

At 1900 that night we were told to be ready to be transferred up to Chungking at 0700 the next

morning. We all rushed around getting ready, however, the next morning the move was postponed. After

a few escort missions, some patrols and a couple of false alarms, the 1st and 2nd Squadrons took off

for Chungking on 9 June.

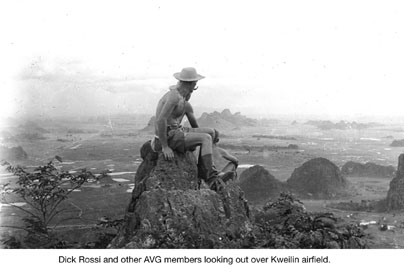

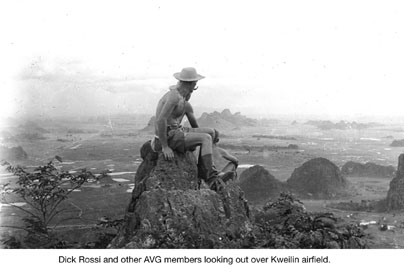

They had built nice quarters for us at the field outside of Chungking, but on arrival we were told

we would be leaving for Kweilin the next day. Since we had several more pilots than planes, a few of

us were to fly on a CNAC DC-3 with the "Old Man." Next day the weather was pretty bad so the P-40

flights were postponed, but those of us on CNAC flew to our destination.

We awakened the next morning to the sound of bombs falling. The Japanese had been making raids on

Kweilin for a long time and there was no opposition to fight them. They sent fighters and bombers to

hit the city and airport - all civilian targets, with devastating effects. The rest of our P-40s

arrived from Kunming that afternoon.

The Japanese had been routinely sending an observation plane over before the main attacks but the

"Old Man" decided to put us in the air early without waiting. So 12 June we got up at 0300 to get

ready to go to the field. We took off at 0520 and, sure enough, at 0600, about eighteen enemy

arrived. We had a big surprise for them. Us. We had fighters at three different altitudes and hit

them hard. Some of the fighting almost got down to ground level. For the first time we saw the

Japanese twin-engine fighters. Our guys thought it was a light bomber. We got ten of their planes

before they got away. No bombs fell on the city. The next night the grateful citizens of Kweilin

came out and gave us a party. We gave them a flyby over the city the next day as a salute.

The Japanese had been routinely sending an observation plane over before the main attacks but the

"Old Man" decided to put us in the air early without waiting. So 12 June we got up at 0300 to get

ready to go to the field. We took off at 0520 and, sure enough, at 0600, about eighteen enemy

arrived. We had a big surprise for them. Us. We had fighters at three different altitudes and hit

them hard. Some of the fighting almost got down to ground level. For the first time we saw the

Japanese twin-engine fighters. Our guys thought it was a light bomber. We got ten of their planes

before they got away. No bombs fell on the city. The next night the grateful citizens of Kweilin

came out and gave us a party. We gave them a flyby over the city the next day as a salute.

The 2nd Squadron moved to another field at Heng Yang. They went on a strafing mission and were

followed back to the field by the enemy. So seven of us from the 1st Squadron were sent over to Heng

Yang at dusk to cover them the next day as they returned from a planned mission. We were supposed to

come right back to Kweilin. We had no baggage, the weather turned terrible and we were stuck there

for ten days without change of clothes. I always carried a toothbrush in my shirt pocket, so I at

least had that.

We were getting a lot of night bombing. When the weather broke, four of us were sent further north

to a field at Ling Ling. There we were getting bombed again at night. At both Heng Yang and Ling

Ling they hit very close to our quarters. We were on alert all day and in the slit trenches most of

the night. At both locations the bombs landed close enough to splatter mud on me.

The Army Air Corp sent General Clayton Bissell out to sign up all of the AVG. Bissell was an old

enemy of Chennault's from his military days. Bissell’s speech to us was filled with demands and

threats as to what would happen to us if we didn’t sign up right then. It didn’t go over well. The

few who stayed on did so out of consideration for the "Old Man" who had become highly respected by

us all.

The Flying Tigers were officially disbanded as of midnight on 3 July, 1942. That was the end of my

combat, but not my flying, career.

The record of the AVG:

We were in actual combat for seven months; we had less than 300 people. As of Dec 2, 1941, there

were 82 pilots out of the original 100 P-40s sent out to Chennault, 78 remained with 62 in

commission, 68 with radios and 60 with armament. There were shortages of just about everything and

no spare parts to speak of. The group has a confirmed count of 299 combat victories with another

probable 600 aircraft destroyed on the ground. Our losses were 4 pilots lost in aerial combat, 7

shot down and killed by anti-aircraft fire during strafing runs, 8 killed in operational and

training accidents unrelated to enemy action. Four were MIA and 3 of those were found to be POWs.

Three died from Japanese bombing raids. One was shot down and seen alive, but no word as to his

fate. The American Fighter Aces Association confirms 20 AVG pilots as Aces with

another 6 pilots achieving Ace status during the next few years.

A Flying Tiger's Story, Page 1

A Flying Tiger's Story, Page 2

Return To Planes and Pilots of WW2 Main Page

All text and images copyright © J.R. Rossi 1995.

All text and images copyright © J.R. Rossi 1995.

Reproduction for distribution, or posting to a public forum without express

written permission is a violation of applicable copyright law.