Try Amazon Audible Plus

Throughout the giant aircraft carrier, the crew could feel the tempo of the ship’s screws increasing speed as a slight shudder passed along the hull. Behind the vessel, the wake churned and boiled as the four large propellers bit into the brown water. Those members of the crew who had the opportunity, looked out upon the sea as another large carrier, the Kearsarge, kept pace a few thousand yards distant. Once again, they were headed off to war, not far from the coast of Korea. There they would unleash the power of the air group, the sole reason for the Oriskany’s existence.

Onboard the U.S.S. Oriskany, Carrier Air Group 102 was hard at work preparing their aircraft for the combat operations that would begin within a few days. Flight operations would likely begin with anti-submarine patrols and reconnaissance flights. Soon, the ship would become part of Task Force 77.01, consisting of the Oriskany along with the carriers Kearsarge and Bon Homme Richard, escorted by the battleship Missouri, the heavy cruiser Toledo and the requisite herd of shepherding destroyers.

On the morning of October 30, flight quarters was called away and

thus began a full day of flying. Before the last engine fell silent on

the flight deck, forty-four sorties were flown; eleven of which were special

photographic reconnaissance missions, with some flown by the F2H-2P Banshees

of VC-61. The 31st of October was quiet, with no flight operations being

conducted as the Task Force steamed to operational area SUGAR off the North

Korean coast. Having arrived on station, the weather steadily deteriorated,

which effectively canceled all flight ops scheduled for next two days.

Finally, on November 2nd, combat operations began in earnest. Ninety-seven

sorties were flown, with many different targets being attacked. All aircraft

returned safely. Another heavy day of combat operations followed on the

4th, with 103 sorties being flown. CVG-102 also suffered it first loss

when a VA-923 AD-3 was hit by ground fire, forcing the pilot to bail out

south of Wonson. It was assumed that the pilot, Ensign Riker, was captured.

Combat missions piled up with 93 sorties on the 5th and 52 more on the

6th of November. Between November 8th and 17th, the air group flew more

than 500 combat sorties, despite three days of heavy weather that grounded

all aircraft. Operations were becoming almost routine, or as routine as

such things can get in a shooting war. Yet, events were about to take a

turn towards the surreal.

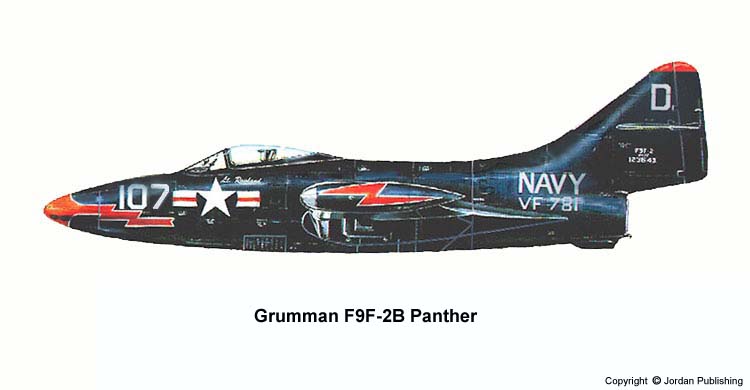

When the pilots of CVG-102 manned their aircraft on the morning of November 18, they did not have the slightest inkling that this day would be significantly different than the prior days of this deployment. VF-781 was to fly the afternoon Combat Air Patrol over the Task Force. Normally, this is a routine operation that was almost always uneventful. Eight of the squadron’s new and improved F9F-5 Panthers took up their patrol split into two divisions of four aircraft. Shortly after 13:40 PM, Oriskany’s Combat Information Center reported unidentified aircraft flying on a heading that would take them directly over the Task Force. Their range was 83 miles, at 345 degrees and closing rapidly. Oddly, these aircraft were not coming in from Korea. Their reciprocal course indicated that they had just taken off from the immediate vicinity of Vladivostok. These were Soviet aircraft. Lt. Claire Elwood’s division of four Panthers was closest to the Russian bogies, and Elwood was ordered to take his aircraft and intercept the incoming Soviets. This was bad timing for Elwood. He had just discovered that his fuel boost pump had failed. With his concern about getting back to ship becoming his first priority, Elwood detached LTJG Royce Williams and his wingman LTJG David Rowlands to execute the intercept, while he nursed his ailing jet, escorted by LTJG John Middleton, back to the Oriskany.

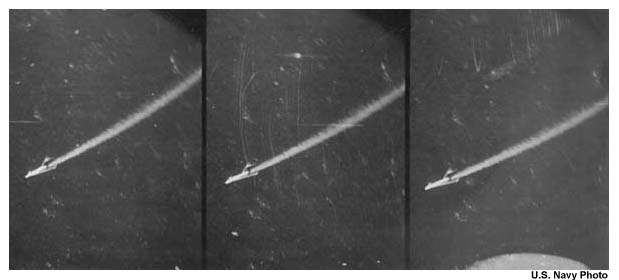

Climbing through 15,000 feet, Williams spotted the Soviet

fighters

very high up. He counted seven vapor trails that marked the MiGs in the

clear sky. They seemed to be flying a loose abreast formation and

Williams caught

sight of the sun glinting off of their wings as the MiGs rolled into a

diving turn and split into two sections. As the MiGs came down into

warmer air, Williams lost sight of the Soviet

aircraft, as they no longer generated the telltale vapor trails. This

caused the two pilots to rely upon CAP Control to keep them informed as

to the position of the intruding MiGs.

Leveling off at 26,000 feet, Williams was startled to see four of the

Soviet

fighters executing a flat-side firing attack from the ten o’clock

position.

Williams and Rowlands broke hard into the MiGs, spoiling their gunnery run. As the Soviets whistled by, recovering to the right, they became strung out. Pulling heavy G loading, Williams continued around in his left turn, rolling out behind the rear-most MiG. Williams’ centered the trailing MiG in his radar ranging gunsight. With a 15 degree deflection and being cleared by the Oriskany to fire, Williams hit his trigger button sending a compact stream of 20 mm shells into the MiG. Chunks of the MiG flew off as heavy smoke poured from the stricken fighter. Rolling slowly, the Soviet fighter fell off on one wing and began to spin. Down it went, without the slightest hint of control. It was last seen by Rowlands at about 8,000 feet above the sea, its spiral ever tightening. There was no time to watch it crash; MiGs were everywhere, intent on killing the aggressive Panthers.

As LTJG Rowlands tried to appraise the tactical situation, he suddenly realized that their emergency break turn had caused him to become separated from Williams, and this left them both in a decidedly dangerous position. Spying the MiG clobbered by Williams, Rowlands, for some unknown reason, followed it down long enough to get some gun camera film of the stricken fighter. Climbing back up to the fight, he immediately found himself targeted by several Soviets who began making slashing attacks at the maneuvering F9F, forcing Rowlands to constantly turn his aircraft to spoil their aim. Hauling around in a tight climbing turn, Rowlands discovered himself in the catbird seat with a MiG dead ahead, oblivious to his presence. Closing the gap between his Panther and the unsuspecting Russian, Rowlands fired a long burst. He observed his cannon shells slam into the Russian jet, tearing great hunks of aluminum out of the fuselage and initiating a thick plume of white smoke. As he closed up for second burst, he spotted another MiG sliding into firing position dead astern of his F9F. Breaking hard, he found the MiG still clinging to his tail. Rowlands watched over his shoulder as the Soviet pilot struggled to get his guns to bear on the Panther and the Russian snapped out several bursts from his twenty-three and thirty-seven mm cannons. Monstrously large red balls came streaming by the belly of the Grumman. Rowlands continued tightening his turn, but the MiG still followed. Finally, he felt the aircraft buffet as Grumman hung on the edge of a stall, and then finally fell out of the lufberry. Surprisingly, the MiG did not jump on him, but poured on throttle and climbed away. Rowlands could not have known that it was dangerous to fly a MiG-15 into an accelerated stall, as it was extremely difficult to extract it from the resulting spin. The MiG pilot could do little more than climb out and look for a better opportunity.

Meanwhile, Williams had his hands full too. Working his way close

behind one of the Soviet fighters, Williams had a perfect set-up at minimal

range. Suddenly, the MiG’s speed brakes popped out, rapidly slowing the

little swept-wing fighter. Pulling back hard, Williams broke up and to

the right to avoid flying right up the MiG’s tailpipe. Seconds later, a

single cannon round from another MiG exploded against Williams’ fighter. This shell

destroyed the rudder controls and blew out the aileron boost. With the

maneuverability of his jet seriously impaired, Williams jinked like a madman in an attempt to disrupt

the enemy pilot’s marksmanship as he dove for the cover

of a nearby cloud bank. Rowlands spotted both the damaged Panther racing

for the clouds, and the MiG in hot pursuit. Diving down, Rowlands

closed on the MiG from dead astern, which was firing snap shots at the fleeing Grumman.

Completely intent on killing the F9F in front of him, the Russian never

saw the dark blue Panther easing in to point-blank range behind him. Closing

to mere yards behind the MiG, LTJG Rowlands pressed his trigger. Silence.

With his guns empty Rowlands found himself overshooting a completely healthy

and hostile MiG. Chopping his throttle, he dumped his speed brakes. Finding

himself flying perfect formation with the Russian, Rowlands looked across

to the Soviet pilot who, in disbelief, stared back at him.

While his squadron mates were fighting off the swarm of hostile MiGs, LTJG Middleton was finally released from escorting Elwood. Turning towards the fight, he pushed the throttle to its stop and roared off to help his comrades. Climbing through the same clouds that his friends were trying to reach, Middleton burst out and spotted the two Grumman jets. Skidding his nose towards the nearest MiG, he fired in a head-on pass. This MiG executed a break, away from the two retreating F9Fs. A second MiG tried a run at Middleton, who quickly reversed, climbing into the sun. Apparently, the Soviet pilot never saw Middleton reverse yet again, diving down for a 90 degree deflection shot. Opening fire, Middleton saw heavy strikes all along the MiG’s length. Swinging in behind the MiG, the American was about to fire again when the MiG’s canopy came off and the pilot bailed out. After the Soviet’s parachute blossomed, Middleton watched the wrecked MiG dive straight into the sea. With other Russian fighters still in the area, Middleton alternately watched his tail and the Soviet pilot until he landed in the cold wave-tossed ocean. That no other MiGs chose to go after the lone Panther was the likely result of the stand-by CAP arriving on the scene after having been catapulted from the Oriskany. They caught a fleeting glimpse of two MiGs turning for home at full speed. Middleton requested that the Soviet pilot be picked up, and orbited the downed airman for as long as his fuel allowed. Finally, he was forced to head for the carrier.

Both Williams and Rowlands trapped safely aboard the Oriskany, with Middleton arriving not long after. No sooner had the aircraft been shut down, technicians began removing the gun camera film magazines for developing. All three pilots were required to sit through long debriefing sessions. With their accounts in hand, the film was reviewed and several conclusions were drawn.

There was no doubt that the MiG-15s engaged were Soviet. Williams was credited with the destruction of one MiG, this being verified by the gun camera film. Middleton was also credited with a MiG shot down. Rowlands was credited with one MiG seriously damaged. Williams’ holed fighter would be quickly repaired and back in service within hours. One question no one could answer was; why did the MiGs attack? Was this the decision of the airborne commander? Or, more ominously, did the order to fire on the Navy jets come from higher in the Soviet chain of command? Clearly, the Soviets had fired first. Their radio transmissions had been recorded and one voice speaking in Russian had authorized the aircraft to fire on the Navy jets. One other observation was recorded. No identifiable markings were observed on the Soviet MiGs. This in itself leads one to conclude that this little Soviet adventure had been planned far enough in advance to remove all markings from the fighters. Moreover, it establishes to a reasonable degree that the motivation was to test the defenses of the U.S. Navy Carrier Task Force. Perhaps, the Soviets were probing the defenses of the task force, intending to pass on anything they learned to the Chinese and North Koreans.

Whatever the reason, the Soviets did indeed learn something. They learned that flying the better aircraft was no guarantee of success. They also learned that the Navy pilots were well trained and highly skilled, not to be toyed with while maintaining any expectation of getting home unscathed. No further Soviet aircraft ventured out to the Task Force, although an eleventh-hour Soviet search was mounted for their missing pilot, and almost certainly proved fruitless. Any concern that this was the beginning of some sort of Russian intervention was soon dismissed. Nonetheless, the Task Force kept a wary eye on the radar for intruders coming south from Vladivostok thereafter.

Months later, President Eisenhower paid a visit to Korea. While there,

he asked to meet the Navy pilots who had taken part in the fight with the

Soviet MiGs. After the meeting, the three awe-struck airmen were admonished

to keep quiet about the incident. Williams, Rowlands and Middleton finished

their tours and returned to their civilian lives. In all probability, they

would have passed into obscurity like so many other veterans. Yet, the

story of their 15 minute engagement with the MiGs of the Soviet Union have

made them symbols of what it means to wear the gold wings of an Naval Aviator.

Bibliography:

Combat Action Report, U.S.S. Oriskany October 28 - November 22, 1952. Available here in .pdf format.

Combat Action Report, CVW-102 November 18, 1952. Available here in .pdf format.

Angelucci, Enzo and Bowers, Peter. American Fighter. Orion Books 1987

Bruning, John. Crimson Sky: The Air Battle for Korea. Brassy's 1999

Sewell, Stephen. Soviet Air Order of Battle, 1950-53.

Standard Aircraft Characteristics: F9F Airplane. U.S. Navy. Available here in .pdf format.