Create an Amazon Wedding Registry

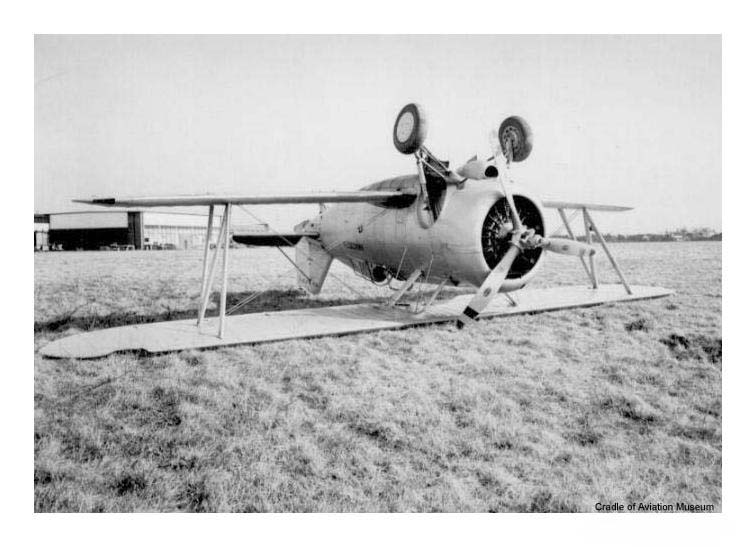

Shortly after the first F2F-1 was delivered, the next Grumman fighter made its first flight. Designated as the XF3F-1, it had been ordered the previous October. Essentially, the F3F was a redesign of its earlier F2F sibling, incorporating a slightly more powerful version of the Pratt & Whitney R-1535 than that fitted to the F2F. This new design produced less aerodynamic drag, and even though it was nearly 600 lbs heavier, it was more than 20 mph faster, although this extra weight resulted in a reduced rate of climb. Perhaps of greater importance to those who tested and flew the fighters, was the significant increase in overall maneuverability that accompanied the redesign.

The development program would suffer from the loss of two prototypes. One of which was caused by structural failure. In August of 1935, the Navy issued a contract for 54 F3F-1 fighters, the first of which was delivered on January 29, 1936. Despite the two crashes, the Navy was still very impressed with the new Grumman and their faith was fully justified once testing had begun on the third prototype.

With the F3F-1 now in service, and being well liked by its pilots,

Grumman proposed that the last aircraft of the order be delivered

with a more powerful Wright R-1820-22 Cyclone producing 850 hp.

Approval was granted by the end of July, and thus was born the XF3F-2.

Fitted with the nine cylinder Wright radial with its much greater diameter,

the XF2F-2 appeared even more portly than its predecessors. Nonetheless,

looks have always been deceiving when it came to Grumman aircraft, and

this one was no different.

Flight testing revealed that overall performance had improved, despite

the significant increase in diameter of the engine and its inherent

drag. Helping to convert the increased horsepower into thrust was a

new three-blade, adjustable propeller. The Navy promptly placed an

order for 81 of Wright powered fighters. And why not? Grumman's little F3F

had evolved into one of the world's best biplane fighter aircraft.

On December 1, 1937, the Navy accepted the first F3F-2, with the last

being delivered on 11 May 1938. It was determined that another

squadron of F3Fs were needed and the Navy placed an order for 27

improved F3F-2 fighters, plus one prototype which was given the

designation of XF3F-3.

These aircraft incorporated subtle improvements

to the aerodynamics (largely to to engine cowling, which was a major source

of drag) and equipment. These ‘cleaned up’ aircraft

managed to attain a maximum speed of 264 mph, or 33 mph faster than

the F2F-1 of two years earlier.

Ultimately, the F3F would remain in

service aboard U.S. Navy fleet carriers until the spring of 1941.

Being retired from front-line service did not consign the F3Fs to

the scrap heap. They would go on to serve in the Naval Reserve and

were extensively used as advanced trainers during the first year of

America’s involvement in the Second World War.

With the day of the carrier borne biplane clearly at an end, the Navy

issued a requirement for a monoplane fighter and announced a competitive

fly-off. Grumman was requested to submit a biplane design, as the

Navy wanted to hedge its bets against the possibility that the

monoplanes would not prove to be acceptable. Grumman proposed a yet

another improvement on the F3F.

It would be longer, and have a greater wing span, with the upper and

lower wings being of the same span for the first time. Designated as

the XF4F-1, Grumman realized that the fighter would be at a distinct

performance disadvantage to the competition, which included the

Brewster XF2A-1 and the Seversky XFN1-1. Therefore, Grumman presented

a strong argument that they be permitted to submit a monoplane design

as well. The Navy agreed and thus was born the XF4F-2.