Try Amazon Fresh

Join Amazon Prime - Watch Thousands of Movies & TV Shows Anytime - Start Free Trial Now

P-47 Thunderbolt: Aviation Darwinism

Chapter Two:

P-47 Thunderbolt: Aviation Darwinism

Chapter Two:

In April of 1939, after losing

more than $550,000 dollars the year before, the board members of

Seversky Aircraft voted Wallace Kellet in as President of the

corporation and Major Seversky lost control of his beloved company.

By September, the company had been reorganized and renamed Republic

Aviation Corporation. Seversky did not go without a fight. By the

time Seversky was finally satisfied with the settlement, it was well

into September of 1942.

Meanwhile, the Air Corps made an effort to keep the new company afloat

by awarding Republic a contract for 13 aircraft based upon the Seversky’s

AP-4. Designated the YP-43, these along with P-35, EP-106 (an export

version of the P-35 for Sweden) and 2PA-204A Guardsman kept the

production lines open and allowed Republic to retain the core of its

skilled workforce.

The YP-43 contract was truly based upon more than keeping Republic

operating. The decision was also predicated upon the outstanding

performance of the AP-4. Much to the delight of the USAAC, the AP-4

proved to be even faster than the Spitfire Mk.I above 22,000 feet.

Although the major contract had been awarded to Curtiss for the low

altitude P-40, the Air Corps was well aware that much of the aerial

combat now underway in Europe was being conducted at higher altitudes

than that which the P-40 was capable of operating at with any reasonable

level of performance.

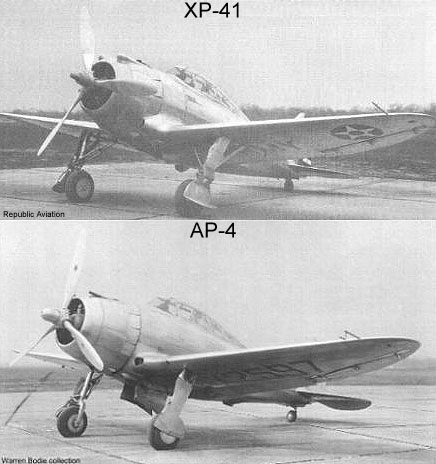

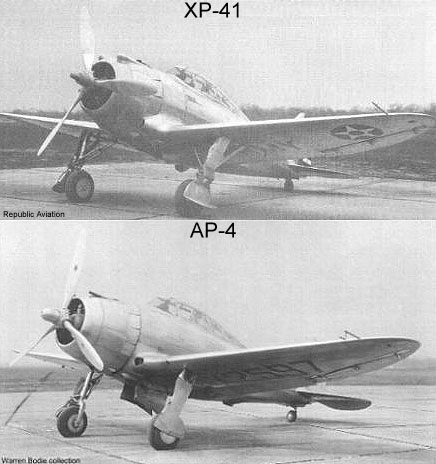

In this composite photo of the XP-41 and

AP-4, the differences between

In this composite photo of the XP-41 and

AP-4, the differences between

the two are evident. The AP-4 has a superior landing gear

design. You can

also see the turbo-supercharger beneath the rear fuselage

of the AP-4. The

XP-41 uses a different air intake than that in the AP-4's wing root.

The XP-41

uses a Curtiss Electric propeller, the AP-4 employs a Hamilton-Standard.

The AP-4 was not the only U.S. fighter to employ a turbo-supercharger

for high altitude performance. Curtiss was flying the XP-37 and the

YP-37, Bell had built the XP-39 Airacobra and Lockheed had presented

the high performance XP-38. Each of these aircraft used the Allison

V-1710 V-12 engine and each was suffering teething troubles.

Ultimately, the Curtiss fighter was relegated to the scrap heap.

The Air Corps stripped the XP-39 of its turbo-supercharger, reducing

the Airacobra to being one of the most ineffective fighters of its

day. The XP-38, after years of development, would eventually go on to

be one of the finest fighters of the war. However, it would not be

combat ready until well into 1942.

A rare and beautiful photo of the new USAAC fighters of 1940.

A rare and beautiful photo of the new USAAC fighters of 1940.

In accending order, a YP-43, an early P-40, a P-39C and a YP-38.

Special thanks is in order to author Warren Bodie for his

generous permission to use his personal photos in this story.

Once a contract for the 13 YP-43 fighters had been issued, Kartveli and

his team began refining the AP-4, reducing the amount of glass

behind the cockpit and moving the air inlet from the leading edge of

the wing root to a location below the engine. This resulted in the

classic oval cowling that continued with the P-47. The redesigned

cockpit glass would also be carried over to the Thunderbolt.

One of the YP-43 aircraft with the

original tail wheel installation.

One of the YP-43 aircraft with the

original tail wheel installation.

The contract called for certain performance guarantees. Maximum speed

was required to equal or exceed 351 mph. The YP-43 bettered that by

5 mph. The fighter was required to climb to 15,000 feet in 6 minutes

or less. The YP-43 was able to exceed this by nearly 400 ft/min. The

first YP-43 took to the air for the first time in March of 1940.

While it lacked armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, it provided the

USAAC with its first fighter that could offer performance on par

with the fighters now doing battle over Europe. However, with only

13 currently on contract, the fighter’s performance mattered little

when the warring powers were putting up hundreds of high performance

fighters with many more under construction. The realization that the

United States was woefully prepared for a modern air war was not

lost on the USAAC. The flurries of design activity were about to

break out into a full snowstorm as America began to come out of her

isolationist muddle.

Soon after receiving the first of the YP-43’s, the Air Corps discovered

that although the new fighter was considerably longer than the P-35,

it was no less prone to ground looping. Eventually, Republic redesigned

the tail wheel assembly. The new design raised the tail of the

aircraft nearly a foot higher. This reduced the tendency to ground

loop and improved vision over the nose. The new tail wheel was no

longer fully retractable. Eventually, 272 P-43 Lancers would be

manufactured. Of these, 108 would be sent to the Chinese to fight

Japan. But, not before many passed through the hands of the

Flying Tigers (AVG).

A P-43A in USAAF Training Command service, circa

1942. Note the revised tail wheel assembly.

A P-43A in USAAF Training Command service, circa

1942. Note the revised tail wheel assembly.

Claire Chennault utilized some of his AVG pilots to ferry the newly

arriving P-43’s to the new owners. In general, the Flying Tigers were

much impressed with the P-43. They liked its excellent speed at high

altitude. This was something that their Curtiss Tomahawks lacked,

having only a single stage supercharger. The little barrel bellied

P-43 made good power right up through 30,000 ft. The Tomahawk, on

the other hand, was running out of breath by 20,000 ft. The pilots

liked the Lancer’s good handling and rapid rate of roll (although

the Tomahawk was a fast roller as well). They were also pleased to

see that the Republic fighter carried the same armament as their

trusty Tomahawks, twin .50 caliber machine guns above the engine

and two .30 caliber Brownings in each wing. The fact that the air

cooled radial engine did not have a Prestone cooling system did not

go unappreciated. The Curtiss could be brought down by a single

rifle caliber bullet striking any portion of the Allison engine’s

cooling system. This was not the case with the P-43. In short, there wasn’t

anything not to like about the P-43.

Some of the AVG pilots went to Chennault and asked if they could

retain some of the Lancers for their use, alongside the Tomahawk.

They pointed out that the Lancer could out-climb the Curtiss and get

far above Japanese formations, something they could seldom achieve

with their P-40’s. However, Chennault turned down their request, and

believed that he had good reasons to do so. Perhaps the primary

reason was that the first P-43’s delivered lacked armor and self

sealing fuel tanks. The risk of his pilots being incinerated was

certainly a real concern for Chennault. A few months later the AVG

ferried additional Lancers in. These were P-43A’s equipped with both

armor and self sealing fuel tanks. However, the self sealing tanks

steadfastly refused to seal. They leaked so badly that Chennault

displayed no interest in these either. The AVG would soldier on

with their Tomahawks and a few P-40E’s until they disbanded on

July 4th, 1942.

Let us digress to earlier events at Farmingdale. In September of

1939 things were really beginning to jump at Republic. The Air Corps

issued a circular proposal in that year calling for a lightweight

interceptor. Curtiss jumped in with a lightened variation of the

P-40 airframe designated the XP-46. Republic submitted a very

similar design which the Air Corps designated the XP-47. Both

aircraft offered the same basic concept: Build the smallest possible

airframe around an Allison V-1710 V-12 engine. This was also the

first design from either Seversky or Republic that was to be powered

by a liquid cooled engine. The major difference between the Curtiss

and Republic effort boiled down to Kartveli electing to use a

turbo-supercharger. As it was, Kartveli’s design never moved beyond

the mock-up stage and the XP-46 showed no performance improvement

over the P-40.

While the XP-47 program was underway, Republic engineers were looking

to improve the performance of the P-43. The result was a contract to

develop the lightweight XP-44. Based upon the P-43 airframe, Republic

planned to install the Pratt & Whitney R-2180 engine in a reworked

Lancer. However, this powerplant did not produce the expected

horsepower and the design team upgraded to the Wright R-2600. This

engine made a reliable 1,600 hp. Yet, it proved to be unsuitable for

turbo-supercharging. Finally, good fortune smiled on the XP-44 in

the form of the P&W R-2800 Double Wasp. With a contract for 80

examples in hand, Republic set out to modify a P-43 airframe to

take the new powerhouse 18 cylinder engine.

To understand how important the R-2800 engine was to become, it is

essential to know that many of America’s best fighters and bombers

of WWII were powered by this redoubtable engine. These include, but

is not limited to, the P-47 Thunderbolt, the F4U Corsair, the F6F

Hellcat and the B-26 and A-26 bombers. The R-2800 that was to be

fitted to the XP-44 produced 1,850 hp. Later variants used in the

P-47M and P-47N produced as much as 2,800 and considerably more

(up to 3,600 hp) on dynamometers.

Slowly, but steadily, work progressed on the XP-44 mock-up, now

known by some at Farmingdale as the “Rocket” (an earlier design

concept by Republic, the AP-10, was also called the Rocket).

Performance projections were impressive. A maximum speed of 402

mph was expected at 20,000 feet. Climb rate should approach, or

even exceed 4,000 ft/min. Armament was to consist of four .50 caliber

Browning machine guns, two mounted above the engine and one

installed in each wing. Fuel capacity was no greater than the P-43.

With the increased thirst of the far larger R-2800 engine, range

would be limited. There is little doubt, however, that the P-44

would have been an effective interceptor.

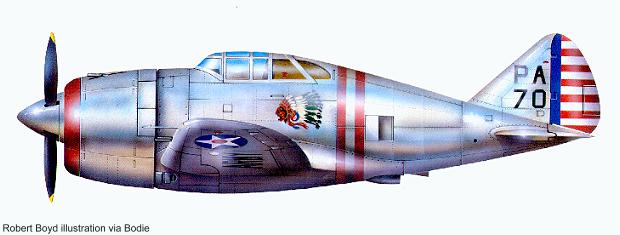

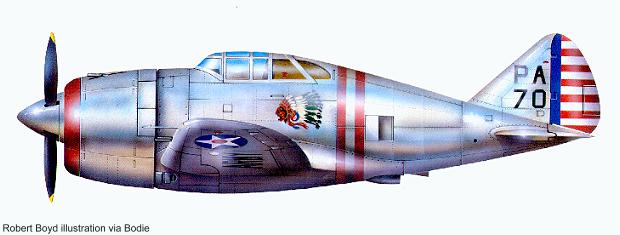

Bob Boyd's terrific

illustration of the proposed P-44 is based upon photos of the XP-44 mock-up.

Bob Boyd's terrific

illustration of the proposed P-44 is based upon photos of the XP-44 mock-up.

Unfortunately, the Air Corps did not need a short range interceptor.

Indeed, as data from the European war was analyzed, it was becoming

very clear that a fighter of far greater capability was going to be

needed. The need to fly even faster, at greater altitudes, over

longer distances was now evident. The Experimental Aircraft Division

of the USAAC called in Kartveli and informed him that the XP-44

contract was cancelled. So was the XP-47 lightweight fighter

contract. They had drawn up a new set of requirements and authorized

a new contract to design and develop a new fighter that would be

designated the XP-47B. The fighter had to meet these new requirements,

some of which were:

1) The aircraft must attain at least 400 mph at 25,000 feet.

2) It must be equipped with at least six .50 caliber machine guns, with eight being preferred.

3) Armor plate must be fitted to protect the pilot.

4) Self sealing fuel tanks must be fitted.

5) Fuel capacity was to be a minimum of 315 gallons.

Kartveli realized that the P-43/XP-44 airframe was not capable of

being adapted to these new requirements. Therefore, he began sketching

a new design on the train returning to New York. He kept the basic

cockpit design, stretched the fuselage, reshaped the tail surfaces

and increased the wing span. When Kartveli arrived at Pennsylvania

Station in Manhattan, he had the basic outline of the fighter would

ultimately break the back of the Luftwaffe in 1944.

Go to Chapter Three

Return to the Planes and Pilots of WWII

Return to the Cradle of Aviation Museum

Return to the Cradle of Aviation Museum

Unless otherwise indicated, all articles Copyright © Jordan Publishing Inc. 1998/1999.

Unless otherwise indicated, all articles Copyright © Jordan Publishing Inc. 1998/1999.

Reproduction for distribution, or posting to a public forum without express written

permission is a violation of applicable copyright law. The Cradle of Aviation

Museum patch is the property of the Cradle of Aviation Museum.

Reproduction for distribution, or

posting to a public forum without the written permission

of Jordan Publishing Inc. is prohibited.