Shop Amazon - Create an Amazon Baby Registry

During the course of the Second World War, the United States produced many exceptional airmen who made their mark and will be remembered as long as people study those most defining years of the 20th century. Many have heard the names of the great fighter pilots, such as Bong, Gabreski and Boyington. However, some of the very best have never achieved the public recognition that they truly deserved. George S. Welch fits into that category. Despite being a featured character in the film epic, Tora, Tora, Tora, Welch simply isn't remembered in the company of the elite scoring leaders mentioned above. In many respects, this would be just fine with Welch. He was never one to seek out attention. Popular American culture has a tendency to accept Hollywood's definition of a hero. This is why names like Chuck Yeager and Pappy Boyington are known in nearly every home. Indeed, there were a great many brave men whose name is no more significant than that of one's bank manager or auto mechanic. Yet, many of these obscure individuals give up nothing in accomplishment and courage to any of the near mythical daredevils that have been popularized in the media. So, who are these men? George S. Welch was one of them. Perhaps his tragic and untimely death obscured his most remarkable life. Or, maybe it was his natural reluctance to live in the limelight. Whatever the cause, the time has come to give credit where it is due, and Welch is due no insignificant portion of glory.

Born on May 18, 1918, George was the son of an influential Du Pont research chemist. George's birth certificate lists his name as George Louis Schwartz, Junior. Having experienced a great deal of anti-German prejudice during the First World War, George's parents decided to formally change the last name of their two boys. Welch was his mother's maiden name, and it was decided to keep Schwartz as the middle name. Contrary to popular myth, George was not related to the Welch family of grape juice fame.>

Young George lived the life that his father's status and income provided. He attending private schools and excelled at sports. His academic abilities were remarkable, although he tended not to make any more effort than necessary. Following his graduation from St. Andrews in June of 1937, Welch attended Purdue and studied mechanical engineering. Having been smitten by aviation, George put in the mandatory two years to be accepted for Army Air Corps flight training. However, with the start of the war in Europe, there were more applicants than openings for Army aviation cadets. Finding himself far down on a long list, George returned to Purdue in the fall of 1939. Finally, after several months, He was ordered to report to Randolph Field for cadet training.

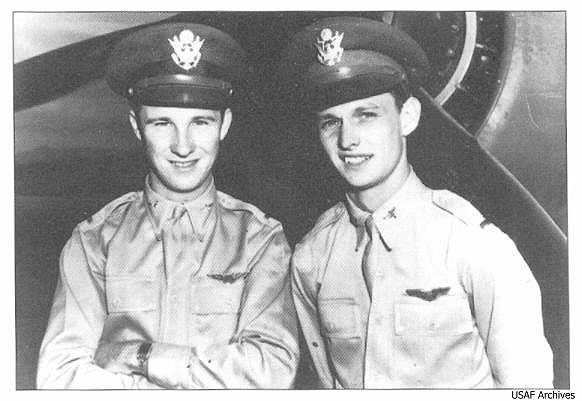

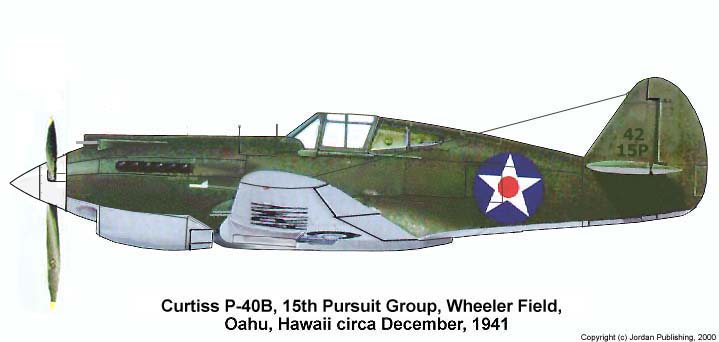

Little more than a year later, Welch was commissioned as a Second

Lieutenant and pinned on the wings of an Army Air Corps pilot. He

received his orders to what was know as a “dream assignment”. George

was to report to the 47th Fighter Squadron based at Wheeler Field on

the Hawaiian island of Oahu. When he arrived in February of 1941,

George was startled to see that the squadron was equipped with antique

Boeing P-26 fighters. His horror was soon assuaged when he was

informed that the Curtiss P-36 and the new P-40 were expected to

arrive in early May. “Good thing,” thought Welch. The P-26 was little

more than an airborne target by early 1941. Flying the little Boeing

against a modern air force would border on suicidal, as was demonstrated

10 months later in the Philippines.

Welch would settle into the slow pace of duty typical of pre-war Hawaii. Working days were short, with most flying suspended before the mid day heat became especially oppressive. There was an abundance of time off and parties were the favorite pastime, frequently lasting from sunset to dawn. George was never the wallflower type and took to the social scene with his typical self-confidence. Life was pretty good for the 24-year-old fighter pilot. However, things were about to change dramatically and forever.

Leaping into the same clothes he had worn the previous evening, George raced from his room just as Taylor burst out of his door. Welch and Taylor had flown their P-40B fighters over to the small airfield at Haleiwa as part of a plan to disperse the squadron's planes away from Wheeler. George grabbed the telephone in the duty office and called Haleiwa. Getting the Duty sergeant on the line, he told him to see that both fighters were fueled, armed and warmed up. He and Taylor were on their way. Running at full tilt, the two pilots piled into Taylor's car. Racing for the base gate, they were strafed by a passing dive bomber. Once on the road to Haleiwa, Taylor drove at breakneck speeds, frequently pushing 100 mph, and covered the winding 16 miles of road in little more than 15 minutes. Sliding to a stop in a cloud of dust and gravel, both men raced to their P-40s, now warmed up and ready. Jumping into the cockpit, Welch listened as his crew chief said, “Lieutenant, we don't have any .50 caliber ammo here. All that you're gonna have is the .30s.” “Ok” said Welch, as he got his harness buckled. The crew chief continued, "We got word that we should disperse the planes, sir." "The hell with that", said Welch, "get off." The crew chief slid off the back of the wing and George pushed up the throttle and taxied to the narrow airstrip. Ignoring the usual pre-takeoff check-list, George slowly fed in full power and roared off the grass with Ken Taylor two minutes or so behind him.

Retracting his landing gear, Welch reached down and grabbed the charging handles for the wing mounted .30 caliber machine guns. Climbing past 1,000 feet, he spotted a large formation of aircraft heading towards the Marine airfield at Ewa. With the throttle jammed full forward, Welch raced in after the Japanese. Lining up on a dive-bomber, he opened fire from very close range. Despite having a gun jam, his fire was dead accurate. The single engine, elliptical winged bomber exploded into flame and nosed straight over into the ground. Pulling off to make another run, Welch felt his fighter take hits from another bomber's rear gunner. Climbing away from the Japanese, Welch felt out the P-40 and determined that there was no damage of consequence. Rolling out into a dive, George headed back for the enemy formation. He arrived in time to see Taylor flame one of the “meatball” emblazoned dive bombers. Zooming in after another of the bombers (later to receive the Allied designation of Val) apparently headed back to its carrier, Welch again closed to point-blank range and sent the plane tumbling into the sea. Taylor had latched on to another of the Vals and sent him crashing into the ground just in from the beach near Barber's Point. Just as suddenly as it began, the sky was empty of enemy aircraft.'

Not far from Wheeler, both pilots headed in and set down on the

devastated airfield to replenish their nearly exhausted ammunition

supply. Fortunately, one of the field's fuel trucks had survived the

attack. Welch and Taylor remained in their cockpits gulping water

provided by their ground crews. Both aircraft were fully fueled and

armed, including the two .50 caliber guns mounted above the engine.

The armorers were unable to clear George's jammed wing gun. No

matter, another formation of Japanese aircraft were spotted heading

in. Welch waved the ground crew away and started the big Allison

engine. As he turned onto the runway he eased up the throttle and

roared down the field. Taylor rolled onto the runway and proceeded

to take off in the opposite direction. As Welch cleared the ground,

he pulled up his landing gear in time to see a Japanese fighter

strafing Taylor on his takeoff roll. Meanwhile, yet another of the enemy

fighters strafed Welch as his P-40 raced down the runway. Rolling into a hard

left turn, Welch felt the landing gear lock into their wells and went straight for the

fighter (an A6M2 “Zero”) that had attacked Taylor. Overhauling the

radial engine plane, he opened fire. His rounds exploded the Zero's

fuel tank and it crashed in a ball of fire just beyond the runway.

Welch then spotted a lone dive bomber headed for the safety of its

carrier

and took out after him at full power. It didn't take long for the

P-40 to close within range. Under a whithering rain of machine gun

bullets, Welch's fourth victim crashed into

the sea. Having used most of his ammunition supply, it was time to

return to Wheeler in order to rearm and top off the fuel tanks.

After George taxied in and cut his engine he

discovered that Taylor had been wounded by the marauding Zero that

had worked him over on his takeoff run. Taylor had ignored the rifle

caliber machinegun bullet that passed through his arm and went directly

for the enemy. Taylor had managed to hit several other Japanese

aircraft, but had not been able to see any of them crash, he was too

busy for that. All he could do was claim two probables. Likewise,

Taylor has stated that at least two other Japanese aircraft fell to

Welch. However, like Taylor's probables, wreckage was never discovered

out at sea. Once again, the two pilots refueled, rearmed and took

off on a third sortie. However, by this time the Japanese carriers

were already steaming away from Pearl Harbor. There would be no more

encounters that day. Much to Taylor's credit, he allowed only first

aid to be performed on his wound before taking off for the third time.

For their actions on the morning of December 7th, both Welch and

Taylor were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Later, Welch

was honored by President Roosevelt at a special White House ceremony.

Yet, this award was certainly less than what was deserved. Hap Arnold

was prepared to approve a recommendation for the Medal of Honor for Welch. However, it

was squashed by a local commander who argued that Welch and Taylor

had taken off without orders. Such was the stupefying mindset of the pre-war

Air Corps. Consider that the Japanese lost just 29 aircraft* during

the attack (plus four other "operational" losses). Now stop and look at what Welch and Taylor had accomplished.

At least 6, and probably 10 of the total Japanese losses were the

direct result of these two pilots. How could the Army accept the

“no orders” argument? What were these men supposed to do? Sit and

wait for some staff officer to issue orders? Enemy aircraft were attacking,

killing sailors, soldiers and airmen. There was no way that they would wait on the

ground for the Japanese to discover their P-40s and destroy them sitting

useless on the parking ramp. They were at war, and they were determined to

make the Japanese pay a price for their treachery, and they intended to do so

immediately.

Welch and Taylor not only met the minimum standards for the MOH, they

defined its meaning. Their actions on December 7th were fall above the

call of duty, and the risk they exposed themselves to was extreme.

When will the Air Force and the U.S. Congress finally give these valiant men their just reward?

If you believe that Welch and Taylor were stiffed by the Air Corps, take out a few

minutes and write or phone your Congressional Representative and

tell them about this injustice. Perhaps after nearly 60 years, we

can get Welch and Taylor the award they truly deserved.

* Japanese Admiral Nagumo was well aware that the American defenses had greatly stiffened. Nine Imperial Navy aircraft of the first wave had been shot down. At least eleven more had suffered some level of battle damage. More resistance awaited the second wave which suffered 20 of its aircraft shot down, nearly half to the Army fighters that had escaped the orignal attack and gotten into the fight in the hands of vengeful pilots. Many of the second wave suffered some battle damage, with nearly 40 aircraft having been hit by anti-aircraft fire and the aggressive American fighters. Indeed, some of these aircraft were beyond economical repair. Adding to those casualties were several operational losses. Nagumo, who had already decided that a two wave attack was all he could afford to risk, was more convinced than ever to turn for home. Additionally, the added specter of an American carrier Air Group finding his task force only reinforced his concerns. In general, Nagumo elected to err on the side of caution.

After December 7th, Welch continued to fly combat patrols around

Oahu. However, the news of his four confirmed victories had been

released to the press and soon he was ordered back to the States.

The country was badly in need of a hero, and Welch fit the bill.

After several hectic months of giving War Bond speeches across

America, Welch finally received orders to return to the Pacific.

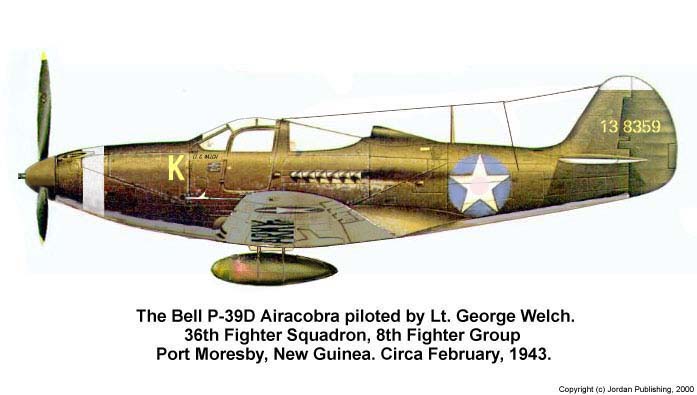

George reported to the 36th Fighter Squadron of the 8th Fighter

Group in New Guinea. The good news was that this squadron had been

seeing combat. The bad news was that is was flying the hopeless Bell

P-39 Airacobra. Welch found himself flying mostly ground support

missions, this being largely due to the P-39's poor combat performance

and its limited range. Certainly, the 37mm cannon was useful against

ground targets, but the Bell was at a serious disadvantage when

facing Japanese fighters. This was largely the fault of it being

fitted with an Allison engine that lacked a two speed, two stage

supercharger. This meant that performance dropped off quickly above

12,000 ft. At the altitudes necessary to engage the Japanese bombers

and fighters, the P-39 was an absolute dog. Welch did not view the lack of performance

at altitude as the primary sin of the P-39. What truly turned Welch against the

Airacobra was its limited combat radius. With the majority of air to air engagements

being fought beyond the reach of the Bell, opportunities to shoot down

more Japanese were nearly nonexistant. Naturally Welch noted

that there were squadrons on his base that were flying the P-38G

Lightning. Now, here was a fighter! Fast, long ranging and equally

important, its twin Allison engines were turbosupercharged. This allowed

the P-38 to climb higher and faster than the P-39. It was everything

Welch wanted and the performance of the P-38 was reflected in the tally of Japanese

aircraft being shot down. George wanted the Lightning, he wanted it badly and cornered

his group commander and inquired as to when 36th could expect to get the P-38. The

answer was: “When we run out of P-39s.” That was all Welch and the

pilots of 36th needed to hear. Virtually any problem encountered in

flight (real or imaginary) resulted in a bailout from that day forward. The operational loss rate

climbed dramatically. Welch found himself in hot water with the Group commander,

who pointed out that George had been very successful in the P-39.

Hadn't he shot down two Vals and a Zero on the one-year anniversary

of the Pearl Harbor attack? That didn't deter Welch, who knew he

could have splashed a hell of a lot more if he'd been flying the

Lightning. Finally, the Brass gave into Welch's repeated requests

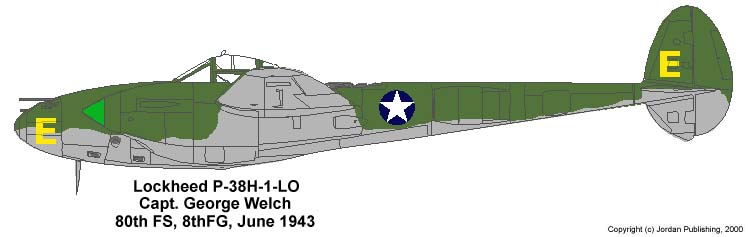

and transferred him across the field to 80th Fighter Squadron.

At last, George had his P-38, and he made the most of it.

On June 21, 1943, he destroyed two Zeros over Lae. Then, two months

later, George downed three Ki-61 Tony fighters near Wewak. Promoted to

captain, Welch was moved to 8th Fighter Group Headquarters. His

biggest day since Pearl Harbor came on Sept. 2, 1943, when he killed

three more Zeros** (these may have been Ki-43 Hayabusa fighters, called

the Oscar by the Allies) and a "Dinah" twin-engine fighter. The startling thing about

Welch's victories is that they all came in multiples. Virtually

every time he found himself in air to air combat, he shot down two

or more of the enemy. Shortly after his final kills, George became

aware that his rather common case of malaria had grown far worse.

Reluctantly, he reported to the base hospital where the doctors were

horrified at his condition and promptly shipped him off to a hospital

in Sydney, Australia. His recovery was slow, and the Air Corps

decided that George had seen enough combat. After flying 348 combat

missions and 16 confirmed kills, Welch was headed home. One can only

wonder what George's final score may have been had malaria not knocked

him out of the war. This writer is convinced that Welch would have

challenged Bong and McGuire for the ace's crown had he remained in

the theater. As it was, malaria sent him home just as things began

to heat up in the SWPA.

** It was not uncommon for pilots to refer to the Ki-43 as a Zero. There were many instances where Army pilots claimed to have shot down a Zero, only to have the wreckage found and properly identified as something else.

George arrived in the States with his new Australian bride. He was

promptly sent out to do more War Bond speeches. Eventually, he was

stationed in Florida where his talents were used in a fighter

tactics development program. Nonetheless, he was still in demand

for Bond rallies and this kept him terribly busy. General Hap Arnold

had recommended Welch to North American Aviation as a test pilot.

In the spring of 1944, George visited with Ed Virgin, the Chief of

Engineering Flight Testing and was offered a position. Welch promptly

accepted the offer and with Arnold's blessing, resigned his commission

with the USAAF. Within two weeks, George was test flying variations

of the P-51 Mustang.

Just over two years after the war ended, Welch would go on to rock the aviation world by doing something that so rattled the newly appointed Secretary of the Air Force, that it was covered up for over 50 years. For that story, please use the link below to go to Part Two - The Amazing George Welch: First Through the Sonic Wall.

Dr. William Wolf, 'Aerial Action... Pearl Harbor Attack', American Aviation Historical Society Journal, Spring 1989.

Al Blackburn, 'Aces Wild: The Race for Mach 1', Scholarly Resources, 1999.

Walter Lord, 'Day of Infamy', Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1957R.

Gordon W. Prange, 'At Dawn We Slept', McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Len Deighton, 'Blood, Tears, and Folly', HarperCollins, 1993.