Shop Amazon - Create an Amazon Baby Registry

THE GREAT CAVALRY BATTLE

OF LIEBERTWOLKWITZ

(14th October, 1813)

by Peter Hofschr÷er

Minature Wargames 42

The first two parts of this series covered the forces involved in some detail. With part IIb there was a map of the battlefield showing the positions of the troops involved so it is assumed that the reader of this part of the article has that information in front of him.

Terrain & Weather

The terrain around and in front of the French position consisted largely of flat-topped hills with gentle slopes. Most of the hollows between them had gentle slopes although a few had steep sides. Between Liebertwolkwitz and Grosspoesna was the 'Niederholz', a wood consisting of alder trees. Due to recent heavy rainfall, most of the hollows were wet and muddy, thus making heavy going for the cavalry in particular. Movement in close order by the infantry was also not easy.

The 1,400 pace wide plateau between Liebertwolkwitz, Gueldengossa and Wachau made particularly good going. The highest point on this hill, the 'Galgenberg' ('Gallows Hill') was an excellent position for the artillery as from this hill, the whole of the battlefield with the exception of Gueldengossa could be seen. Furthermore, it was impossible to see over this hill from the south, so the enemy would be unaware of any movements and troops to the north of this hill.

The soil was chalky lime. It had been softened by the rain and the ploughed fields between Liebertwolkwitz, Wachau and Gueldongossa did not make the going easy. It is not surprising that the horses soon became tired and as a consequence of this, their pace soon dropped to a walk and the battle was broken up by long pauses.

The weather on 14th October 1813 was damp and foggy. The fog lifted about midday and it became sunny. The battle began in earnest only when the fog had lifted.

The Plan of Battle

The reports coining into Wittgenstein's headquarters at dawn confirmed his view that the French were falling back and were now on the heights running from Markkleeberg to Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz. This led Wittgenstein to believe that he should follow up quickly and attack what he thought would only be a rearguard. His preparations for the battle were therefore rather hasty.

Wittgenstein ordered the cavalry of the vanguard to move up to Liebertwolkwitz via Croehern and Gueldengossa. The infantry of the vanguard was to occupy Croehern.

Prince Eugene of Wuerttemberg was ordered to form his men up in two lines and to advance from Madgeborn to Gueldengossa and to take up a position on the heights to the north of this village.

Prince Gortschakow II was ordered to march through Stoermthal and then deploy into two lines.

General von Kleist was ordered to send his Reserve Cavalry to Croebern to support Pahlen whilst the main body of his corps was to remain in Espenhain in reserve.

The 3rd Russian Cuirassier Division followed up Kleist's Reserve Cavalry later on. Rajewski's Grenadier Corps also remained in reserve.

Murat's position is clear from the map. He also had a division of the Young Guard in Holzhausen and Augereau's Corps on the Thornberg to the south of Leipzig in reserve, although they were not involved in the action described below. His instructions were to delay the Allied advance for as long as possible, but not to get involved in serious fighting.

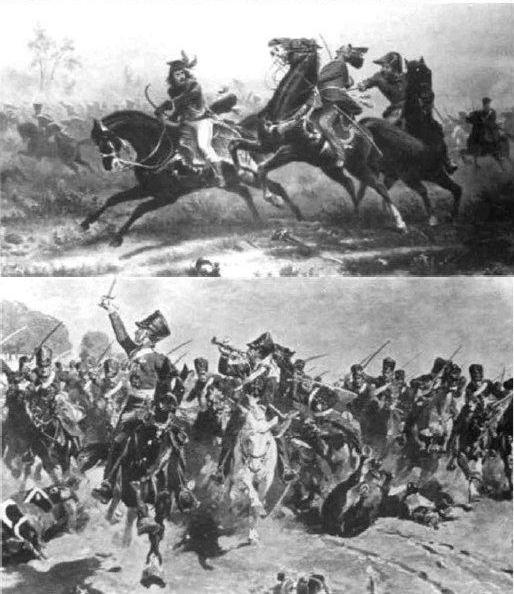

Photo 1) The Neumark Dragoons approaching Wachau.

Photo 2) The first attempt to take Murat prisoner fails!

The First Moves

Pahlen's column moved forward. His vanguard, Illowayski's Cossacks, reported back that the area between Wachau and Markkleeberg was occupied in strength by the enemy and a strong force of his cavalry was in position near Markkleeberg and that he was already skirmishing with them. Pahlen sent the Grodny Hussars up to support the Cossacks, but his main body continued towards Liebertwolkwitz. Once Pahlen reached Gueldengossa; he sent the Sumy Hussars forward, supporting them with his Prussian regiments. He wanted to hold this position until the Prussian Reserve Cavalry and Duka's Cavalry Division arrived. Although a large force of French was in front of him, the cavalry were dismounted so he was not expecting an immediate attack.

Wuerttemberg's Corps moved up too and halted when he saw the strong French force in front of him.

Murat appeared, members of his retinue fired off their pistols at Wuerttemberg's scouts and Murat himself rode off to give his cavalry the order to attack Pahlen.

Baron Diebitsch, Barclay de Tolly's Quartermaster General rode up to Pahlen and ordered him to attack the French whom he perceived to be retreating. Pahlen obeyed the order of his superior, even though he thought it wrong. Wuerttemberg took Diebitsch to the other side of the hill and showed him the long line of enemy cavalry who had mounted up in the meantime and the mass of cannon, saying: "Now, take a look yourself". This demonstration succeeded in getting Diebitsch to change his mind about the enemy's intentions, but it was too late to change his orders; the battle had already begun.

The French batteries opened up and the Sumy Hussars desisted from the advance. Division L'Heritier followed by Division Subervie moved forwards in a column. The Russian Battery Nikitin was threatened and started firing canister at the leading French regiment. The Sumy Hussars became aware of the threat, turned and charged the leading French regiment, throwing it back. The next French regiment then pushed the Russian Hussars back.

In the meantime, the Neumark Dragoons had moved up. Pahlen cried out to them: 'Now, brave dragoons, at them, you'll soon throw them back!" This the dragoons did, but their advance was halted by the next line of French dragoons. They had, however, gained enough time for the Sumy Hussars to rally and the threatened battery to limber up and get away.

The next unit to arrive was the Silesian Uhlans who rode up to hill 162.5 and saw the cavalry battle that was taking place. The East Prussian Cuirassiers also moved up to this position and let the Sumy Hussars pass through their ranks before charging the halted French in front of their position. The French were in the process of rallying when hit by the East Prussians and in the flank by the Silesian Uhlans. The French were thrown back and pursued by the Prussians. The Uhlans got as far as the battery on the Galgenberg. Three or four fresh regiments of French cavalry counter charged the Prussians in the front and flank and drove them back to hill 162.5 where the Neumark Dragoons, who had just rallied, hit the pursuing French in the flank and forced them to desist from their pursuit. At this point, an officer of the Neumark Dragoons almost took Murat prisoner, but was killed by his groom.

There was now a pause in the action whilst both sides rallied and rested .

This first part of the action gives a good indication of the tactics used by the cavalry of this time. Charge and counter charge, followed by a pursuit which was broken off once the enemy brought fresh troops into play. The French seem to have favoured the column which did not allow them to take full advantage of their superiority in numbers, whilst the Allies were somewhat more flexible with their cavalry, using squadrons to attack the flanks of the French, thereby forcing back superior numbers.

Events on the Allied Left Flank

At first, there were only minor skirmishes between the Poles and the Cossacks on this flank. When a few formed squadrons of Poles moved up to clear the Cossacks, the Grodno Hussars were sent in as re-inforcements.

At about the same time that the Prussian Reserve Cavalry debouched from Croebern, an order from Murat to the 4th Cavalry Corps arrived. It was instructed to attack the allied cavalry between Croebern and Gueldengossa. Roeder, the commander of the Prussians, saw the French start their movement and deployed the Brandenburg Cuirassiers and 7th Horse Battery to cover the remainder of his force whilst it debouched from Croebern. The French halted their movement, not wanting to take on the Prussians. Roeder then sent the Brandenburgers off to Gueldengossa, following the Silesian Cuirassiers whilst his brigade of militia cavalry was sent to support the Cossacks and Grodno Hussars which were deployed near the Auenhain sheep farm.

The French, seeing the Prussian cuirassiers moving off, but apparently not seeing the militia cavalry moving up, went over to the attack. The Russians were put to flight, but the Poles were quickly repelled by the militia cavalry which made a surprise attack on them from dead ground. The militia did not follow up vigorously and the fighting on this flank degenerated into half hearted skirmishing.

Events on the Allied Right Flank

Paumgarten was moving and by around 11.30am, he had reached Seifertsheim (see map). His orders were to attack Liebertwolkwitz from the north. When he reached the Kolm Berg, Paumgarten could see that the French were covering the flat area to the north of Liebertwolkwitz in force. He decided to attack the French and his hussars and border troops (Grenzer) engaged the enemy skirmishers deployed on the west bank of the ditch running to the cast of the Kolm Berg. However, the Austrians made little progress.

The Austrians brought up a horse battery and finally took the western batik, but the fire from the French artillery pieces was so effective that the advance was halted. The battle on this flank bogged down.

Events in the Centre

Capture of Lieberwolkwitz by the Austrian 4th Corps

At about noon, Count Klenau received Wittgenstein's order to attack. He was in Grosspoesna with his reserve cavalry. Klenau was aware that the only way to will the cavalry battle was to take Liebertwolkwitz itself and thereby force the French artillery deployed near the windmills (W.M. on maps) to withdraw. Regiment Erzherzog Karl moved up through the wood, ready to attack, the 2nd Battalion in front followed up by the 1st. On its right flank was a battalion of the Regiment Lindenau. The trees hid this deployment from the French. The Erzherzog Ferdinand Hussars and border troops were used to push back the French voltigeurs. Austrian artillery was deployed to support the forthcoming attack. All was ready when the order arrived at noon. Klenau attacked immediately.Map 1) The attack of the Prussian Reserve Cavalry. Note the way in which Murat used the Galgenberg to mask the movement of his cavalry reserves. Note also the way in which the Allies strove to gain the flanks of the attacking French. The cavalry regiment in the centre was not the "Westpreuss" (West Prussian) as shown on this map, but the "Ostpreuss" (East Prussian). This printing error is not repeated on the next map!

To protect the infantry from counter measures from the French cavalry, Klenau had the Erzherzog Ferdinand Hussars deploy in skirmish order to their front whilst formed bodies of the Hohenzollern Chevauxlegers covered the flanks. They were supported by the 2nd Battalion of the 2nd Walachian Border Regiment deployed in skirmish order with close order supports. The Corps Reserve Cavalry followed up to the rear to prevent any counterattack by the enemy.

Klenau's deployment was most thorough and skilful. He used the terrain to hide as many of his movements as possible. All three arms were used to support each other and he kept the advantage of surprise up his sleeve for as long as possible. Such a well organised attack was likely to meet with success.

This attack came as a complete surprise to the French. Although the men positioned around the edge of the town offered a strong resistance, panic and confusion broke out within Lieberwolkwitz itself. The guns positioned around the entrance to the town fell back, heightening the confusion.

A bitter street battle followed. The three battalions of Austrian infantry took almost all of the town and only the church and a few houses at the northern edge remained in French hands. The French counter attacked and regained some of the town. The Austrian cavalry and border troops had in the meantime forced the French artillery by the windmills to withdraw and thus the objective of Klenau's attack had been attained. Austrian re-inforcements moved up and by 2pm, all of Liebertwolkwitz was in Austrian hands. However, the French, particularly the artillery, fought back so well that all attempts to break out from Liebertwolkwitz were beaten back.

The way was now clear for the cavalry battle in the centre to continue.

Photo 3) The church in Liebertwolkwitz. It changed hands severa1 times during the course of the battle. Moreover, the unfortunate residents of this town had sought refuge in it. It must have been a little crowded inside.

Further Cavalry Battles in the Centre

We left the battle here at the point where both sides had come to a halt and were rallying and reforming their tired troops. The Allies formed up to the south of hill 162.5, with Roeder's Prussian cuirassiers forming the front rank and the two Russian hussar regiments (Sumy and Lubny) forming the second.

The French did not remain inactive whilst this was going on. A number of squadrons of dragoons were used in skirmish order to attempt to disrupt the Allies. The French dragoons were armed with a long carbine which was superior in range to the firearms carried by the Allies and they made quite an impression. The Allies detached their flankers and sections of the Tschugujew Uhlans and Cossacks to deal with this threat from the French. Officers and even troopers of both sides engaged in duels and fights with each other.

Once the French had rallied their cavalry, they moved over to the offensive again. Murat placed Division Milhaud to the fore with the front rank consisting of the 25th Dragoons to the right and the 22nd Dragoons to the left, both in line. The 20th, 19th and 18th Dragoons were formed up in a column of divisions (each of two squadrons) behind the centre of the front rank. Division L'Heritier and the two light divisions were placed to the rear.

The advancing French pushed the Allied skirmishers out of the way and moved forward to hill 162.5 at a trot. Pahlen ordered Roeder to counter attack. The Silesian Cuirassiers wheeled left and charged the enemy with the East Prussians. The Brandenburg Cuirassiers moved through the Russian skirmishers and followed up in reserve. This force hit the right flank of the French line which was thrown back onto the following column. The Brandenburgers added their weight and the French were forced back. The French formations were not yet broken open and the Prussian pursuit had little effect at first. Once, however, the French began to open up, many were cut down. Murat was almost taken prisoner again. The Prussians continued the pursuit right back to the Galgenberg and into the French guns. They cut down a number of the gunners and attempted to drag off some of the guns. At this point, the French staged a counter attack. Milhaud's Division and the light cavalry were to hand. Infantry hurried from Wachau to save the guns and the beaten dragoons halted. The Prussian cuirassiers were surrounded and had to hack their way out. Losses were high, particularly for the Silesian Cuirassiers. The fighting mass of friend and foe worked its way back to the Prussians starting point on hill 162.5.

The Allied artillery batteries were unable to fire on the French as both sides were mixed together. However, fresh cavalry were to hand. The Neumark Dragoons charged, supported by the Silesians and Tschugujew Uhlans and some of the Russian hussars. The French offered little resistance. Their exhausted horses fell down ditches where they were set upon by Cossacks.

Another pause in the action followed. Both sides rallied their troopers under cover of their flankers. The artillery ceased fire: The Allies were joined by squadrons of Austrian cavalry from the Hohenzollern Chevauxlegers and Ferdinand Hussars.

The skirmish action continued and increased in intensity. The French maximised the effect of their better carbines. Platoons and even whole squadrons of dragoons rode up to 200 paces from the enemy and shot at them. The Allies could not fire back effectively as their firearms were out of range. Instead, they were forced to make continuous attacks on the French, tiring their horses out merely to stay alive. The Silesian Uhlans alone made some 16 attacks on this day. The French later attempted to attack the Prussian cuirassiers with a large force whilst they were still rallying, but this attack was thrown back by the Tschugujew Uhlans who launched a surprise attack from dead ground into the flank of the French.

The Decisive Phase of the Cavalry Battle

It was now between 2pm and 2.30pm. It must by now have been clear to Murat that he was not going to achieve his objective of defeating the enemy cavalry whilst they were on their approach. march. He should have pulled his forces back and remained on the defensive, but his fighting spirit had been awakened by the battle and he made ready for another attack.

The battle for possession of Liebertwolkwitz was continuing, the French artillery on the Galgenberg engaged in counter battery fire with Allied guns opposite. Under the cover of this fire, Murat formed up his troopers again. Division Milhaud led the attack, with Division L'Heritier following up. Both divisions were in a column of squadrons. Some reports mention that Polish cuirassiers led the attack and this is quite possible. The light cavalry was formed up to the rear.

At 2.30pm. the French guns ceased firing and out of the smoke, the French cavalry came galloping up to hill 162.5 as fast as their horses would go. This impressive mass of horsemen struck fear in the Allies. Even the holes torn in their lines by the Allied artillery on their flanks did not stop them. The Allied skirmishers were driven back on their main bodies.

The column continued towards the Brandenburg Cuirassiers who started to counter charge. The two right squadrons of this regiment had an overlap and wheeled left into the flank of the French. The Silesian Uhlans supported this movement. Parts of the Sumy and Lubny Hussars covered the Brandenburger's left flank.

Klenau, seeing what was going on, used his initiative and sent part of his light cavalry off to attack the flank of the French. Two squadrons of Erzherzog Ferdinand Hussars and six troops of the Hohenzollern Chevauxlegers closed in on Milhaud's flank, the O'Reilly Chevauxlegers and Kaiser Cuirassiers moved up in support. The first wave brought the French to a halt, the second threw them back. The French broke and were pursued over the Galbenberg and nearly as far as Probstheida (off the map) where the sight of fresh French formations brought the Allies to a halt. The Allies reformed and withdrew to the other side of the Galbenberg in good order where they were met by Duka's Russian Cuirassier Division which had just arrived on the battlefield. It was however not to see action as the French cavalry had been driven from the battlefield for good.

Map 2) The final French charge. Murat left the left flank with too little protection. The capture of much of the town of Liebertwolkwitz by the Austrians had obliged the artillery earlier deployed to the south of the town to retire. Klenau's charge into the flank of the French sealed their fate once and for all that day.

The Recapture of Liebertwolkwitz

The battle was not yet over. Although the French cavalry was beaten, the battle itself was to continue until nightfall.

The Allies had won the initiative and gained a partial victory. What they needed to do now was clear the remaining French, from Liebertwolkwitz and thereby force the French to withdraw from their position. Such a defeat of Murat may well have brought about a quicker settlement to the Battle of Leipzig. This was, however, not to be. Wittgenstein did not use his initiative, but stuck to the letter of his orders to 'undertake nothing serious' despite the change of circumstances.

Even Klenau, who still held most of Liebertwolkwitz, was not re-inforced. Neither was he ordered to withdraw. He was left out on a limb in a position that could not be held for much longer without positive action to clear the heights to the west and north of the town. The initiative passed back to Murat. At 4pm, his infantry launched a new attack on Liebertwolkwitz.

With three fresh regiments, he attacked the town from three sides whilst the divisions of the 5th and 2nd Corps between Liebertwolkwitz, Wachau and Markkleeberg started to move forwards. The Allied artillery stopped the latter movement, but the storming of Liebertwolkwitz was successful. The Austrians were driven back after a hard fight, holding on to the church and the southern edge of the town. Between 5 and 6pm, the French took the church. The last of its Austrian defenders were trapped against a wall by a narrow gateway where they were slaughtered.

After nightfall, Klenau withdrew from the town. Camp was struck on the battlefield.

Photo 4) The gate where a number of Austrians were massacred is no longer there. A memorial stone has been placed close to its original site.

Losses

The Austrians lost a total of 33 officers, 1515 men and 125 horses in this battle; 5 officers and 408 men were killed, 26 officers and 973 men were wounded and 2 officers and 134 men taken prisoner.

The Prussians lost 24-25 officers, 270-280 men and 250-260 horses, not including any losses sustained by the Militia Cavalry Brigade which must have been minimal.

The Russians losses can only be estimated, and it would not be unreasonable to say that they must have lost around about the same as the Prussians.

This would make the total Allied losses 80-85 officers, 2000-2100 men and 600-650 horses.

There is little reliable information available on French losses. According to Martinien, they lost 2 generals and 96 officers, excluding the Poles, so their total loss was probably a little more than the Allies. The Austrians alone had taken over 800 French prisoners.

The bulk of the allied casualties were in fact suffered by the Austrians. They had committed a good 6,000 men to the various assaults on the town of Liebertwolkwitz and suffered heavy casualties in the bitter street fighting. Regiment Lindenau lost 17%, Erzherzog Karl 13 %. The five Austrian artillery batteries which stood under fire for a long period lost about 20%. Two thirds of these losses were wounded or prisoners. Again, these figures are much lower than one tends to see on a lot of wargames tables.

An analysis of the casualties is also interesting. The worst loss by an allied cavalry unit was sustained by the Silesian Cuirassiers. Dead and wounded totalled 14 officers, 169 men and 80 horses. This was the unit that was surrounded when attempting to drag off French guns Moreover, it undertook a number of charges during the course of the battle. It started the battle with 564 men and thus lost some 32% of its strength. The losses to horses were lower than to men which was not usually the case as horses, being bigger targets, tended to suffer greater losses than their riders. The bulk of these casualties were probably men wounded hacking their way out from around the French guns. More typical of the losses sustained in such a see saw cavalry battle spread over a day were those of the Brandenburg Cuirassiers, always in the thick of the action. They lost 2 officers, 20 men and 30 horses from 440, or a mere 5%.

Actually involved in the fighting were between 5,600 and 5,800 allied cavalry troopers. Total losses were around 10% of that figure. Had the Silesian Cuirassiers not got themselves into such a predicament, then the total loss would have been around 8%. This was for a whole day's fighting in which numerous charges and counter charges were undertaken with skirmishing in the intervals. Most wargames the author of this article has seen tend to have much higher rates of casualties. The cavalry tended to suffer its greatest losses from artillery fire when attacking and from enemy cavalry when broken and retreating. On neither occasion were they capable of offering any resistance. When they were, losses were negligible.

Photo 5) The memorial stone in the churchyard in Liebertwolkwitz. It was placed there in October 1984 by local people.

Conclusions

Despite their superiority in numbers, the French cavalry suffered a defeat here. Victory in the various cavalry actions did not go to the larger force, but to the one that gained the flank of the enemy and kept a formed reserve up his sleeve the longest. The French seemed to have made little effort to protect the flanks of the columns of dragoons they sent forward. True, the light cavalry was deployed in such a way that it could have protected the flanks of the main attack, but once the front of the main body had been thrown back, the light cavalry went with them. In the final attack launched by Murat, he should surely have used his light cavalry to keep the Austrians at bay. That attack may well have succeeded if he had done so.

The Allies spread their cavalry formations over a wider front and in less depth. They did this on the same terrain as the French, so there was nothing stopping the French from deploying in the same fashion. The result may well have been different as the French would have been able to bring their superior numbers into play.

Much is said of the poor quality of the French cavalry at this time and that could be offered as the reason for their defeat. However, despite a lack of training and unsuitable mounts, the French cavalry was capable of mounting several attacks, rallying and pursuing and keeping a formed reserve, which must indicate a certain level of tactical ability and training. Moreover, the French cavalry shone when it engaged in skirmishing. Only experienced troops make good skirmishers, so it is the view of the author of this series of articles that many historians tend to underrate the French cavalry of 1813. It came close on a number of occasions to beating the Allied cavalry and it was only Murat's poor tactical deployment which deprived them of victory.

The Allied cavalry must also be praised. Faced by an enemy superior in numbers who mounted several large attacks over the course of a day, the Allied cavalry never hesitated to counter charge and showed great flexibility. They always got the overlap and always gained the flank. They almost carried off French guns as trophies. Murat himself came close to being captured twice. The Prussians and Russians acted together as one, the Austrians showed great initiative and their intervention brought about victory. Only orders from the Army Command and lack of initiative by Wittgenstein prevented Liebertwolkwitz from being a significant Allied victory.

Photo 6) The centre of Liebertwolkwitz. The timbered house has been restored to how it looked at the time. The remaining houses were rendered over subsequent to the battle. They are slowly being restored to their original state. The lack of motor vehicles indicates which part of Germany Liebertwolkwitz is in!

Bibliography

By far the most comprehensive and thorough work written on this battle was Hugo Kerchnawe's Kavallerieverwendung, Auflaerung und Armeefuehrung bei der Hauptarmee in den entscheidenden Tagen voir Leipzig which was published in Vienna in 1904. Other books cover the battle, but in not as much detail.

Another solid work which covers this battle is Rudolf von Friedrich's Geschichte des Herbstfeldzuges 1813. The 2nd Volume, published in Berlin in 1904 was the source of most of the maps used.

A number of regimental histories of units involved were consulted, but little would be gained from listing them here.

French sources consulted included:

L. A. Picard's La cavalerie dans les guerres de la revolution et de l'empire published in 1895. This work attempts to excuse Murat's performance and, in the opinion of the author of this series, does not do a very good job of that. An explanation and analysis of his actions may have been more appropriate.

Other French works covering this campaign tended to lack any real details of this battle.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Philip Wright for his help in locating the French sources.

| Part I | Part II | Part IIb |