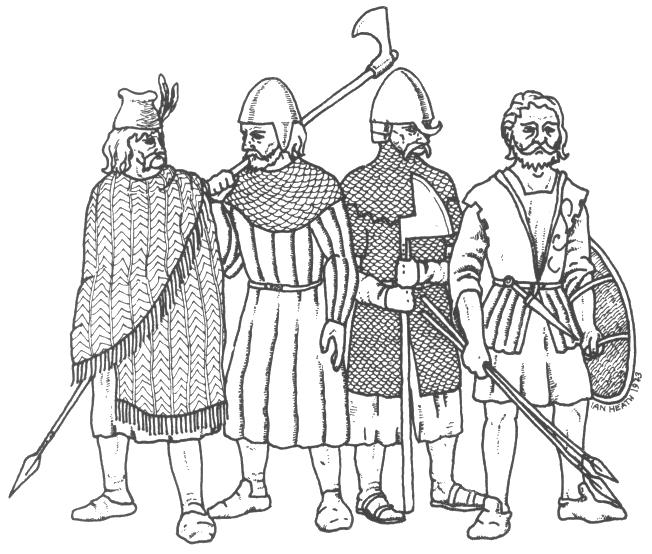

Above: alternative Gallowglas helmets; on the right is a 15th Century padded one.

Typical Irish sword of the 16th Century. Note ring at base of hilt with tang passing through it, and square ended scabbard. Irish swords of this period were usually straight and large. Note different types of scabbard on the following two illustrations, especially those with a dagger strapped to the outside of the scabbard.

Flags shown in print of Irish force at battle of Erne Fords, 1593. Colours not known.

Infantry flag on left, cavalry on right.