Create an Amazon Business Account

Join Amazon Prime - Watch Thousands of Movies & TV Shows Anytime - Start Free Trial Now Create an Amazon Business Account |

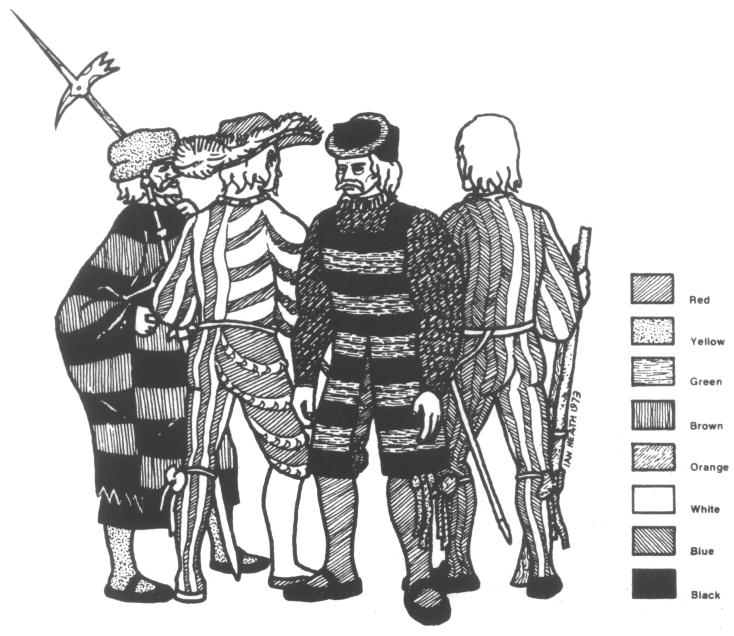

Lansknecht armour, probably of an officer, about 1550 (Tower of London Armouries). |

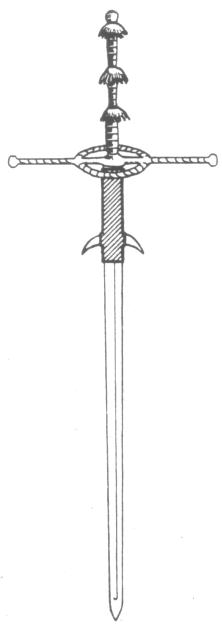

A two- handed sword of the type characteristic of the Lansknechts. Note the hilt, long enough to give a secure double-handed grip, and the 'Ricasso', a section of the blade covered with leather or material so that the grip could be shortened for close-quarter work. The small 'tongues' act as a guard. |

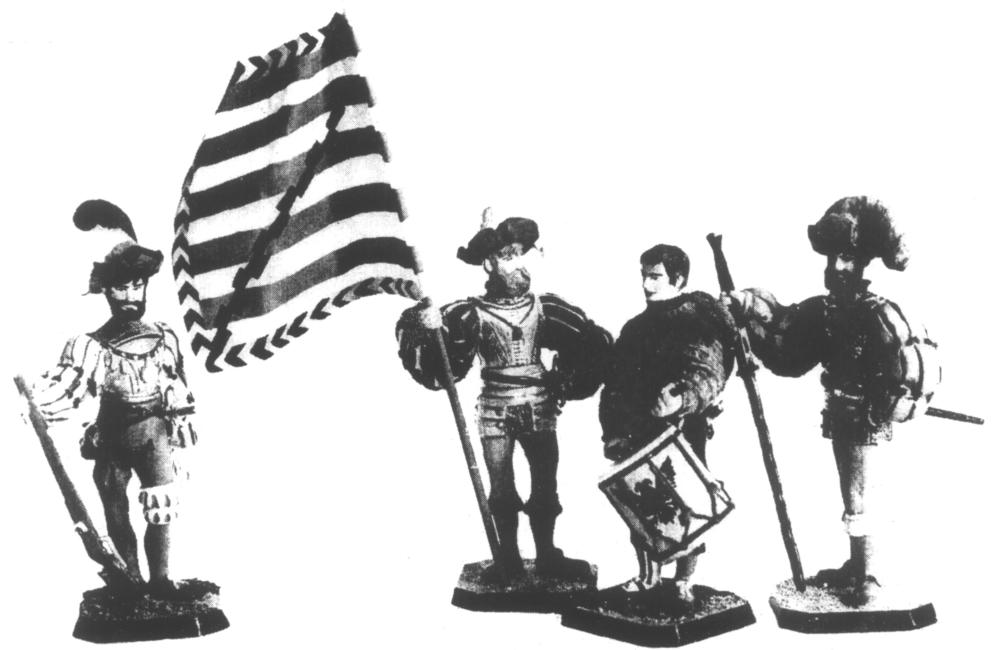

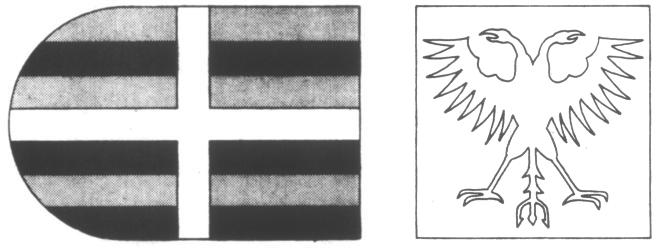

Left flag, probably of the Black Band, at Pavia, 1525. Colours white, red or blue(?) and black. Right Imperial Eagle flag, black on yellow, 1525. Eagle is usually crowned, but not in this example. |