Try Amazon Audible Premium Plus and Get Up to Two Free Audiobooks

The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt had the distinction of being the heaviest single engine fighter to see service in World War Two. Parked alongside any of its wartime contemporaries, the Thunderbolt dwarfs them with its remarkable bulk. Despite its size, the P-47 proved to be one of the best performing fighters to see combat. Produced in greater numbers than any other U.S. made fighter, the story of how it came to exist is at least as interesting as its many accomplishments.

The development of the Thunderbolt was a classic instance of design evolution tracing its origin back to Alexander P. de Seversky and his highly innovative aircraft of the early 1930’s. Seversky, a Russian national, was a veteran of World War One. Seversky flew with the Czarist Naval Air Service and suffered the loss of a leg as a result of being shot down in 1915. Unfazed, he managed to convince his commanders to allow him to fly again using an artificial leg. Ultimately, Seversky was credited with no less than shooting down thirteen German aircraft before the Czarist government reached an armistice with the Kaiser Wilhelm in 1917. In early 1918 Seversky was appointed by the Czarist Government to study aircraft design and manufacturing in the United States. While he was in the U.S., the Communist revolution made it exceptionally dangerous to return home. Seversky had heard of the mass executions of his fellow officers and promptly applied for American citizenship.

Even in his early years in America, Seversky was obviously skilled at promoting himself, because he managed to gain a position as a test pilot and consultant with the fledgling United States Army Air Service. Seversky’s brilliance was quickly recognized and he was assigned as an assistant to General Billy Mitchell. Over the span of the next 8 years, Seversky applied for no less than 360 U.S. patents. This included a gyro-stabilized bombsight purchased by the Army Air Corps. He even managed to obtain a commission in the Army Air Corps Reserve. Major Seversky formed a company registered as Seversky Aero Corporation. Unfortunately, the small company did not survive the stock market crash of 1929. Undaunted by this serious financial setback, Seversky attracted enough investors to form a new firm. In February of 1931, he was elected president of the new Seversky Aircraft Corporation. The Major quickly surrounded himself with several expatriate Russian engineers including Michael Gregor and the man who would ultimately head the P-47 design team, Alexander Kartveli.

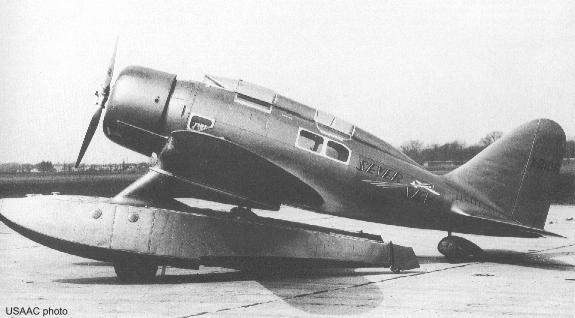

The Russian connection quickly produced fruit. The first design was

manufactured under contract by Edo Aircraft Corporation of College

Point, Long Island, NY. Designed as a low wing monoplane design,

this first aircraft, designated the SEV-3, was a floatplane. Edo,

being the leading manufacturer of aircraft floats, was an ideal

choice when one considers that Seversky had no manufacturing facilities.

Even with Edo’s expertise, construction still took two years, largely

due to the lack of capital funds. Finally, in June of 1933, the SEV-3

took off from Long Island waters with Seversky at its controls. Painted

in a stunning bronze, the SEV-3 was one of the more advanced aircraft

in the world. Several months later and fitted with a more powerful

engine, the SEV-3 set a new world speed record for amphibians. One

major contributor to the plane’s excellent speed was its distinctive

thin, but broad semi-elliptical wing. This basic wing design would

still be seen on the P-47 a decade later.

Seversky turned out several variations on the SEV-3 theme over the

next several months and tried to sell the design to the Air Corps.

The company finally gained a contract to manufacture a new Air Corps

trainer designated the BT-8. It was very easy to spot the resemblance

to the original SEV-3.

Eventually a further development of the SEV-3 would be submitted for

an Air Corps fighter design competition. It was the only two seat

aircraft in the competition and this combined with serious engine

difficulties would result in a poor showing. Typical of Seversky’s

resilience, the Major returned to Farmingdale to design an aircraft

that could win the next competition the following year.

The new fighter incorporated a redesigned fuselage and tail section.

Designated the SEV-1XP, it was flown to Wright Field in Ohio for the

1936 fighter competition, from which, it emerged as the winner. Further

development resulted in an Air Corps order for the fighter, now given

the new designation P-35. The one glaring fault of the P-35 was its retractable

landing gear layout. In an era where flush folding landing gear were becoming

common-place on new fighter designs, the P-35 used a method that was minimally

effective in reducing drag, as compared to a fixed landing arrangement.

The Seversky’s gear simply folded back into a pod-like housing that protruded

from the underside of the wing. When seen alongside many of the worlds newer

fighter designs, such as the Hawker Hurricane, Supermarine Spitfire, Curtiss

Hawk 75 and Germany’s Messerschmitt 109, the P-35 appeared awkward and decidedly

less sleek. Nonetheless, the new P-35 offered performance on par with most of the

world’s best fighters.

As the later half of the 1930’s crept by, the obvious increase in tensions in Europe

and Japan’s war with China created a greater demand worldwide for combat aircraft.

Seversky, feeling the severe pinch of the depression combined with American

isolationism was quickly being overwhelmed by red ink. The Major began marketing

his aircraft and design experience to several nations. Soon, orders began

arriving from Japan, the Soviet Union, Columbia and Sweden. These

production runs kept the factory running and provided enough cash

to make payrolls. Nonetheless, it was becoming obvious that Seversky

would not be able to continue selling aircraft that were rapidly becoming

obsolescent. All the export aircraft were based upon SEV-3 and SEV-1XP

technology. If a new opportunity did not come along soon, Seversky would

be forced to closed their doors.

That new opportunity arrived in 1939. That year, the Army Air Corps held

yet another Pursuit Competition. Two aircraft were entered by Seversky.

The Major entered his AP-4 design and Alexander Kartveli submitted the XP-41.

In most respects, these two fighters were very similar. The largest, and

ultimately, the deciding difference was the Major’s use of turbo-supercharger as

opposed to a single stage engine driven mechanical supercharger on Kartveli’s

XP-41. The turbo-charger installation was unusual in that it was mounted in

the fuselage behind the cockpit. This required extensive ducting to carry exhaust

gases to the rear of the fighter and, return the compressed air to the engine’s

induction system. This complexity was offset by the outstanding high altitude

performance of the aircraft. The XP-41, even with its flush folding landing gear

offered only mediocre performance at low altitude and demonstrated a rapidly

degrading level of performance above 15,000 feet.

The AP-4 was clearly the better

of the two and certainly the best performing fighter in the competition. No matter,

Curtiss won the competition with its XP-40 largely based upon its ability to begin

full production immediately. Fortunately, the AP-4 was not ignored. A contract for 13

Service Test examples was issued. However, these would not be manufactured under the

watchful eye of Major Seversky. He would be deposed as the head of the company that

he had created and molded. The AP-4 would be refined and manufactured by a hastily reorganized

company and the new fighter would be known as the Republic YP-43.