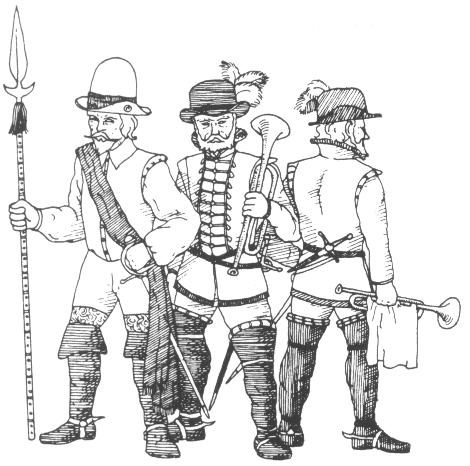

An English officer of the 1580s carrying a Partisan and wearing a sash, usually red in colour; and two views of an English mounted bugler of the same period: note ruff-type collar, lace on front of jacket, and dagger carried on belt.

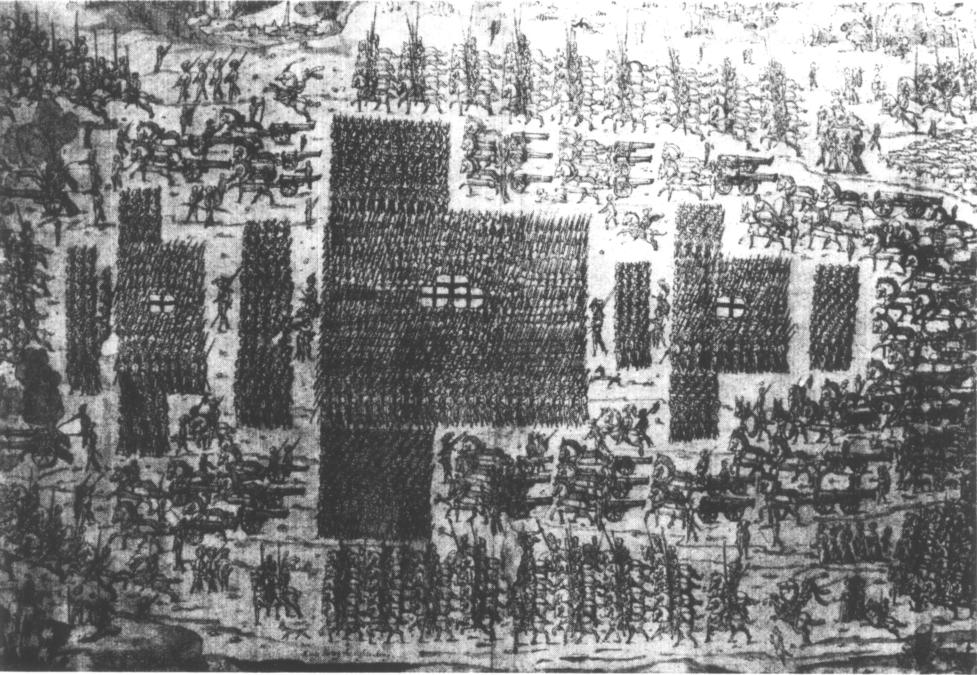

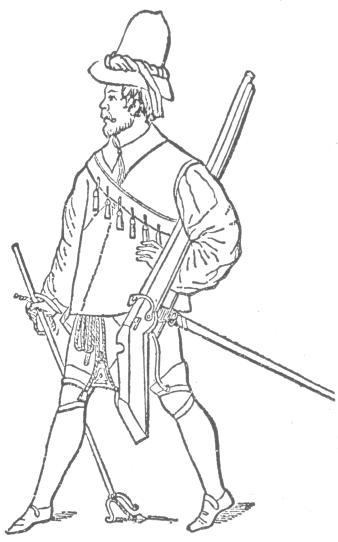

A man of the London Trained Bands of Henry VIII’s period in white jacket with red St George’s cross on front and rear (Drawings by Ian Heath).