Join Amazon Prime - Watch Thousands of Movies & TV Shows Anytime - Start Free Trial Now

Create an Amazon Business Account

Part 22 - the Muscovites

by George Gush

RUSSIA IN THIS period was still primarily the Grand Duchy of Moscow. It was only in 1480 that the Tsar dared withhold annual tribute from the Tartars, and the extension of Russian power thereafter, against Poles, Swedes and Tartars, and into Siberia and the Cossack lands, was slow and often reversed. Such as it was, the rise of Muscovy was largely due to the adoption of European military ideas, well before the thorough reforms of Peter the Great. The pattern of her armed forces was created by this process: the basis a semi-feudal, Tartar-influenced cavalry horde, gradually supplemented by European types, and by mercenaries including Poles, Tartars, and, above all, Cossacks.

The cavalry army

'All his men are horsemen, he useth no footmen, but such as go with the ordinance and labourers' wrote Richard Chancellor in the 1550s, and even a century later cavalry still greatly exceeded infantry in the Tsar's field armies.

This arm was drawn from three main sources; first, the entourage of the Tsar and princes. From Ivan the Terrible's day (1533-82) there had been a 'Dvorani' or household force of 15,000 paid cavalry or noble pensioners.

Second came the rest of the nobility and their followers. Ivan regularised their service by paying 110 great nobles to report once a year with their 65,000 retainers; the rest were only summoned in emergency.

Third were the 'Sons of the Boyars' (Boyar=Noble), a lesser military class who received small holdings of land in return for military service. Created by Ivan III (1462-1505), they were registered in the towns and mustered in town contingents, accompanied by varying numbers of armed servants.

The resemblance to the Turkish system is obvious (see part 10), and the general tactics and equipment also followed the 'Turkish or Eastern pattern; the better-off wore mail or scale armour, and helmets of Eastern type, though contemporary observers were particularly struck by the splendour of their appearance, with costly furs, silks and satins, gilt embroidery and inlays, elaborate, often jewelled, collars and horse trappings, and even silver mail. Servants and retainers often wore padded clothing, adequate to stop an arrow.

Weapons included light lances, various maces (especially the 'kisten' shown), scimitars and light javelins, and by the later 16th century a few carried a case with two 'dags' (short pistols), but the Russian weapon par excellence was the Tartar composite bow; relatively few carried lances, and they rode jockey-style, like the Tartars, with knees drawn up, ideal for the horsearcher but not for standing the shock of a lance charge. Russian horses were small but wiry geldings again unsuited to shock tactics.

Most of the lighter cavalry carried only a dagger or sabre beside the bow. Tactics were loose and irregular, relying on surprise, envelopment (assisted by the Muscovites' usual vast numbers) and fire, and avoiding close combat. Though not highly disciplined they were organised on similar lines to the Tartars, with squadrons of 100 and regiments probably 1,000, but the only divisions clearly observed were the five (later six) large 'Polks' or divisions into which the whole force was divided. These had their own standards (of St George) and commanders, and seem to have comprised Left and Right Wings, Van, Reserve, Main Body, and Light Cavalry (one section was known as the Broken Band and supplied men for 'sudden exploits'). They had many trumpeters, but the leaders gave tactical signals on small brass drums (there were also some huge drums carried on platforms across four horses and beaten 'in a wild manner' by eight men each!)

The Streltsi

Ivan the Terrible was responsible for a general reorganisation of the Russian forces, and perhaps his most important reform was the creation of a standing body of infantry, the Streltsi (sharp-shooters), a hereditary, town-based force. There were 12,000 in Moscow, of whom 2,000 formed a guard for the Tsar, and the total corps perhaps reached 40,000 strong. Though there seem to have been some Streltsi with pikes in the early 17th Century, they were normally armed with long arquebusses or muskets, clumsy matchlocks with straight stocks, and also carried sabres and berdish poleaxes with a spiked haft which could be used as a musket rest. Though useful, they showed in the later 17th Century much of the Praetorian arrogance and rebelliousness of the contemporary Janissaries (who may have been the model for their corps), and the Moscow Streltsi were bloodily suppressed by Peter the Great in 1698, the rest being disbanded in 1710.

Streltsi regiments were divided into companies or Sotnia of 100, and (at least in the 1670s) ranged from 600 to 1600 men. They wore no armour except helmets, and their issued clothing seems to have been semi-uniform from an early stage, with the regiments distinguished by colours, including red and green. The following list of the 1674 Moscow Streltsi probably gives an idea of earlier colours as their style had certainly changed very little.

Regiment Buttonhole- Trim,

(named after Colonel) Dress Lace Lining Hat Boots

1st Igor Lvotokhin Red Raspberry Raspberry Gray Yellow

2nd Ivan Poltev Lt. Grey Raspberry Raspberry Raspberry Yellow

3rd Vasili Bokvostov Lt Green Raspberry Raspberry Raspberry Yellow

4th Feodor Golovinsk Cranberry Black Yellow Gray Yellow

5th Feodor Alexandrov Scarlet Dark Red Lt Blue Gray Yellow

6th Nikifor Kolobov Yellow Raspberry Lt Green Gray Red

7th Stepan Ivanov Lt Blue Black Brown Raspberry Yellow

8th Timofei Poltev Orange Black Green Cherry Green

9th Petr Lopokhin Cherry Black Orange Cherry Yellow

10th Feodor Lopokhin Yellow-orange Raspberry Raspberry Raspberry Green

11th David Vorontzov Raspberry Black Brown Brown Yellow

12th Ivan Naramansk Cherry Black Lt Blue Raspberry Yellow

13th Lagovskin Bilberry Black Green Green Yellow

14th Afanasii Levshin Lt Green Black Yellow Raspberry Yellow

Illustrations

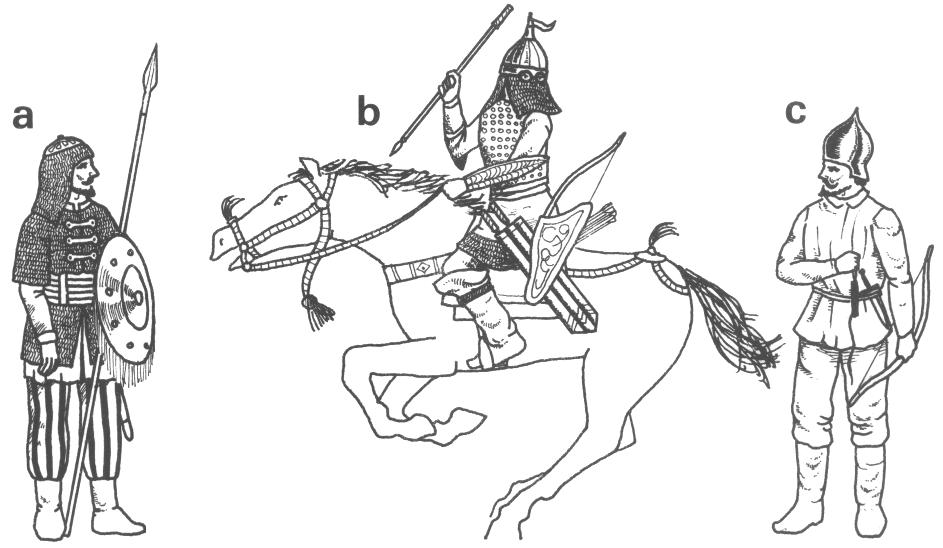

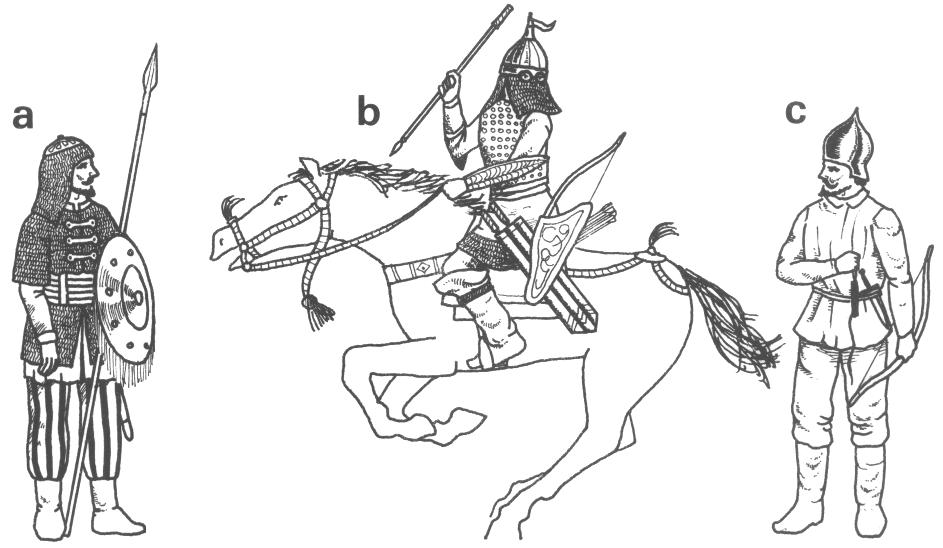

a 16/17th Century Russian cavalryman wearing 'saucer' helmet with mail hood (popular in the Caucasus) and mail shirt with plate 'corset'. He has a short straight sword and convex metal shield with fringe round edge, of a type often used by Russians. b Russian noble cavalryman in Sassanid-style helmet, with pennon, face-mask and neck protector of mail, studded brigantine and mail shirt. Note soft boots held up by a type of gaiter. He is armed with bow and three javelins in a case.

c Russian light horse archer of the 16th Century in padded doublet. Carries knife and bow, no sabre. Note riding crop hanging from right hand little finger.

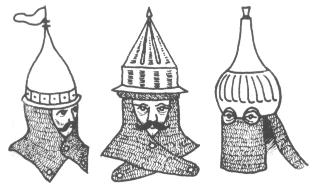

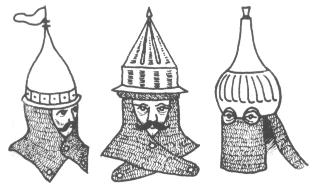

Some alternative helmet types (to b above):

|

|

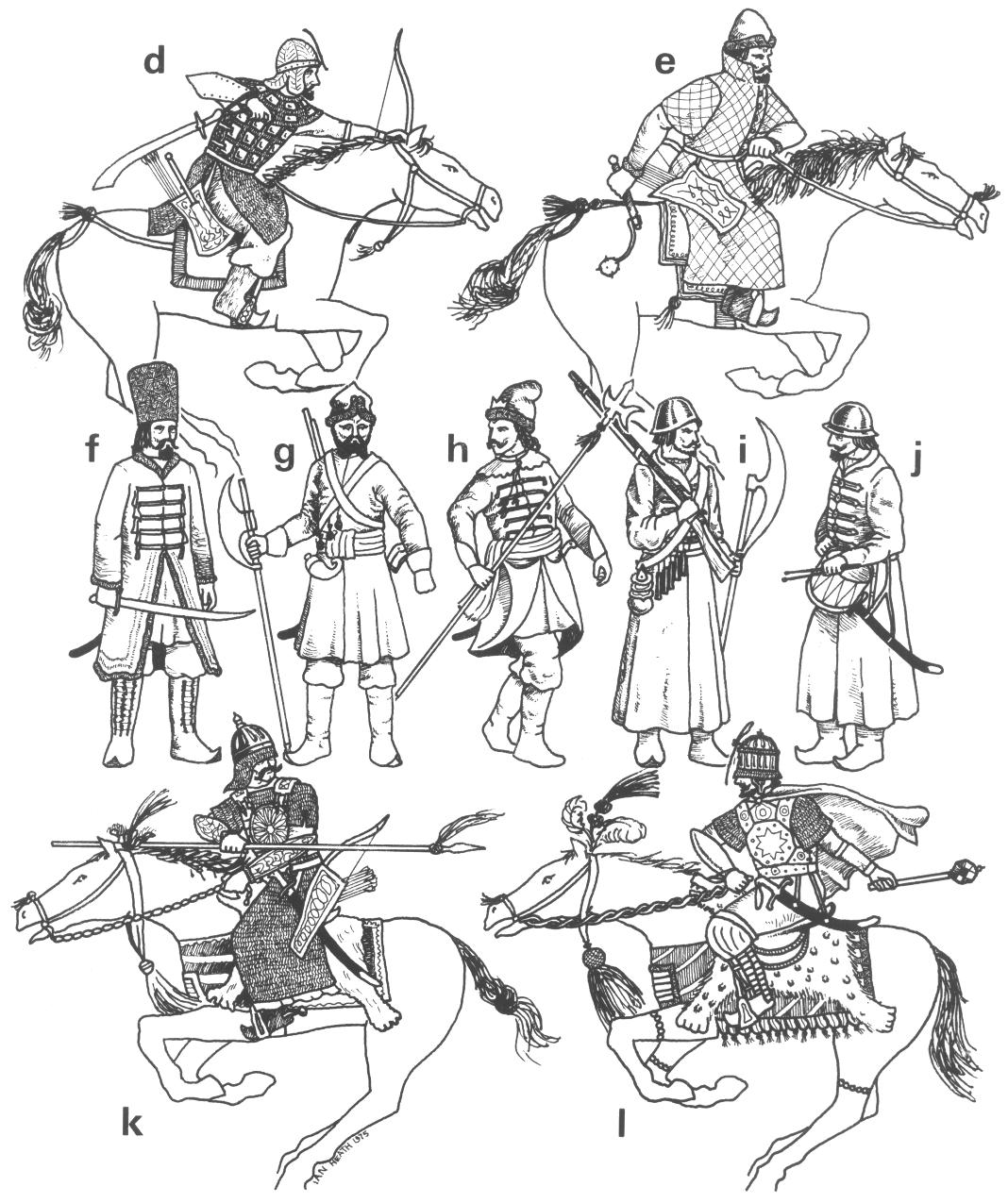

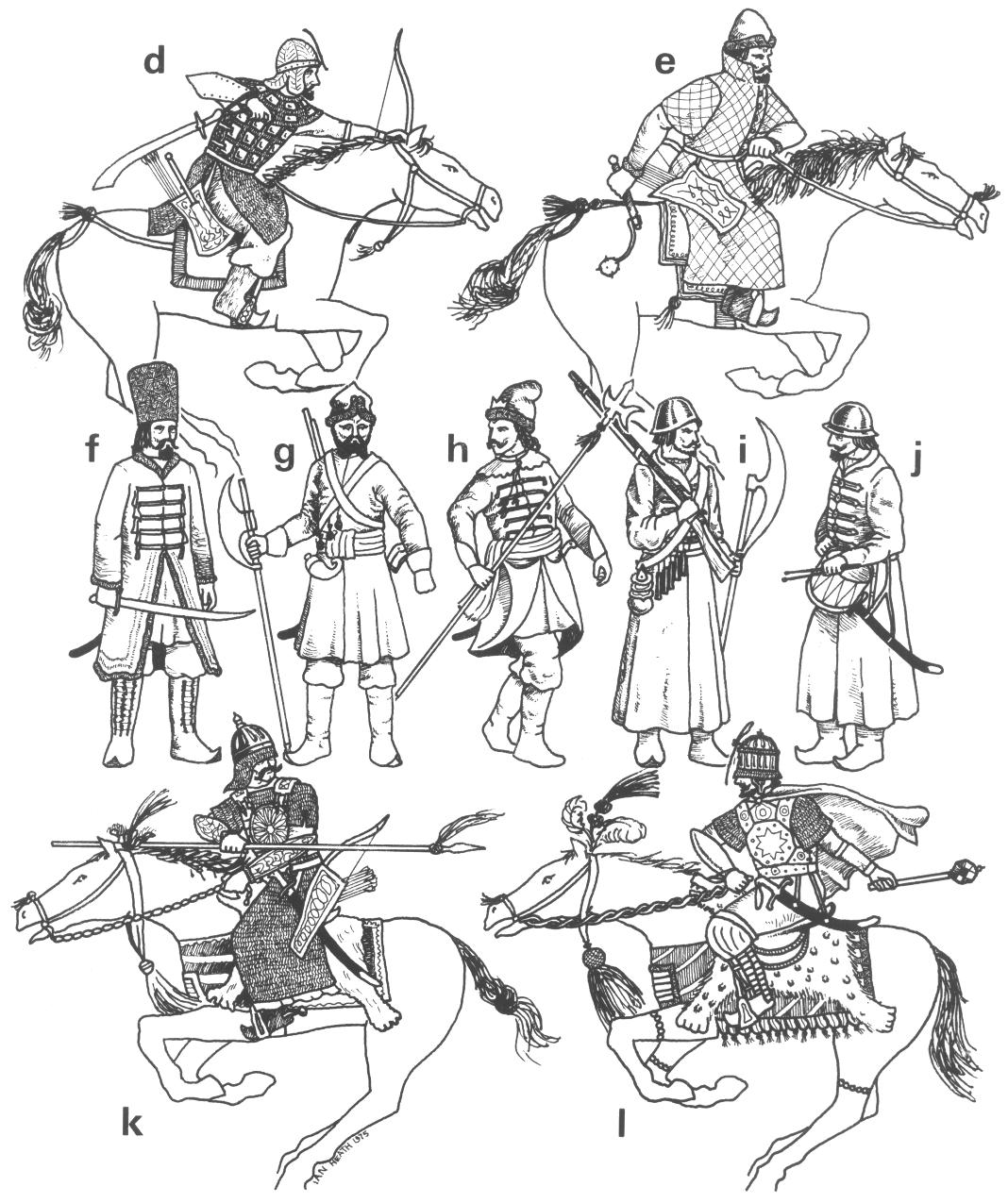

d 16/17th Century Russian cavalryman. Sabres often had loops, so they could hang from the wrist. Corselet and cape are of combined mail and plate. His helmet is a padded type with a metal band to support the nasal. A light javelin is held in an extra pocket of his quiver. e Cavalryman with padded protection. The weapon in his hand is a 'kisten', an iron knob on a stout leather strap attached to a short handle. Note also riding position, with knees drawn up like a jockey. f Senior officer or noble of l6/l7th Century. Note very-tall hat, decorated coat skirts and boots. g 17th Century Streltsi with musket slung on back and berdische axe. h Streltsi officer with halberd. Note corners of overcoat turned back, and hat with metal crown, the sign of an officer. i an early 17th Century Streltsi wearing a strikingly modern-looking helmet.

j Streltsi drummer. His dress does not distinguish him from other Streltsi. Note very small drum. k Noble cavalryman in mail reinforced with plates, vambraces on forearms and helmet with mail aventail covering the eyes. Armed with bow, sabre and light lance. Could also have kisten or mace, round shield, or small axe-cum-hammer. l Mounted Boyar or noble, probably an officer, in war dress. The faceted mace is a sign of high rank. He wears a Russian type of corselet of plates, the chest plate being octagonal, with mail sleeves and oriental-type vambrace. Helmet has high-mounted nasal, ring of plates attached by mail, and mail, to which side plates are attached, hanging over the eyes. His boots are also armoured, but as usual with Russians of this period lack spurs (they use instead the whip hung from the wrist).